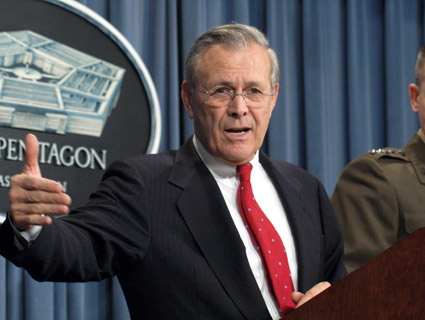

Donald Rumsfeld.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/5446241057/in/photostream/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

While the Obama administration has been soft on pursuing justice for victims of Bush-era human rights violations, it’s at least comforting to know that the US court system is picking up a teensy bit of the slack. On Monday, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in a 2-1 decision that a civil lawsuit brought by two American men against Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and the US government alleges sufficient evidence to proceed.

Plaintiffs Nathan Ertel and Donald Vance, who had been working as security contractors for Shield Group Security in Iraq, claim that they were unjustly detained and subjected to psychological and physical torture shortly after they started to suspect that their company was engaging in bribery and weapons trafficking. BBC News reports:

The men began feeding information [regarding the alleged corruption] to US government officials in Iraq until, in April 2006, the company confiscated their credentials to enter the Baghdad Green Zone…according to their court pleadings.

Then, US military personnel detained them, confiscated their belongings, handcuffed and blindfolded them and took them to a military base in Baghdad, where they were fingerprinted, strip-searched and locked in a cage.

They were then taken to Camp Cropper near Baghdad International Airport, where they “experienced a nightmarish scene in which they were detained incommunicado, in solitary confinement, and subjected to…torture for the duration of their imprisonment – Vance for three months and Ertel for six weeks”, the court wrote, reiterating the men’s allegations.

The decision [PDF] stated that command responsibility does in fact apply to top-ranking government officials in times of war, and that there was enough of a case to hold the former defense secretary, not just individual soldiers or the military commanders, accountable.

Here’s an excerpt from the court documents (emphasis my own):

The plaintiffs allege that Secretary Rumsfeld then directed that the techniques in place at Guantanamo Bay also be extended to Iraq. The plaintiffs claim, for instance, that Secretary Rumsfeld sent Major General Geoffrey Miller to Iraq in August 2003 to evaluate how prisons could gain more “actionable intelligence” from detainees. In September 2003, in response to General Miller’s suggestion to use more aggressive interrogation policies in Iraq, and as allegedly “directed, approved and sanctioned” by Secretary Rumsfeld, the commander of the United States-led military coalition in Iraq signed a memorandum authorizing the use of 29 interrogation techniques (the “Iraq List”), which included sensory deprivation, light control, and the use of loud music.

David Rivkin, Jr., Rumsfeld’s attorney, promptly issued a response that spouted national-security talking points so predictable that it’s almost redundant to post them:

Having judges second-guess the decisions made by the armed forces halfway around the world is no way to wage a war…It saps the effectiveness of the military, puts American soldiers at risk, and shackles federal officials who have a constitutional duty to protect America.

With the Bush and Obama administrations’ repeated (and rather successful) efforts to block cases pertaining to post-9/11 abuses, it’s easy to get cynical and conclude that this lawsuit, too, will get derailed and vanish in the news cycle clutter. However, some human rights lawyers and activists are claiming that the appeals court ruling itself is already an important victory in the fight against government impunity.

“This shows that the courts are open and willing, as they should be, to listen to the claims of victims of torture, and whether or not it gets the media attention it should, there is still, thankfully, the opportunity,” Melina Milazzo, a fellow in the law and security program at Human Rights First, told Mother Jones. “This is huge progress. So many of these cases have been dismissed before the merits can be reached. This is now the highest court that has ruled this way in such a case…but what is really interesting is that the two justices who decided that Rumsfeld did not have qualified immunity said that US laws provide civil damages remedies to aliens, so it would be shocking not to provide it to our own citizens.”

Ertel and Vance’s suit might also have a greater chance of succeeding because they are American citizens, not foreign accusers, Milazzo added: “In practice, it is not clear whether or not the constitutional protection would apply to foreigners, but in this case, it is abundantly clear.”

Alexander Abdo, a staff attorney in the ACLU’s National Security Project, also lauded the legal and political significance of Monday’s court decision, stressing that the case may help to reaffirm that the government cannot get away with institutionalizing “enhanced interrogation.”

“The most significant aspect of the Obama and Bush administrations’ attempts to avoid accountability is that they have convinced courts that the higher an executive official, the less accountable they should be,” Abdo told Mother Jones. “The purpose of these constitutional prohibitions is to be applied to high-level executives…[and] the principle of the rule of law states that no high-ranking official has free license to commit the worst kinds of crimes based solely on the level of their office.”

The appeals court decision comes less than a week after a district court ruling in Washington, DC, in which a judge decided that an Army vet is allowed to sue Rumsfeld for damages related to (you guessed it) torture at the hands of American military personnel in Iraq.

All in all, it has been a solid few days for human rights advocates, and probably a frantic and rather inconvenient week for Rumsfeld’s lawyers.