Illustration: Steve Brodner

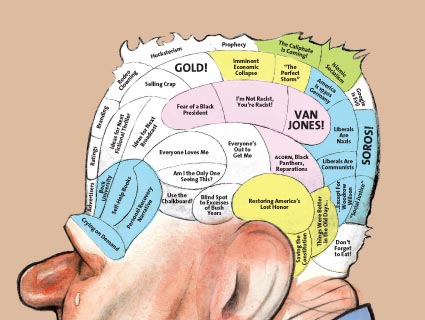

IN THE SPRING of 2009, as the titanic fight over President Barack Obama’s health care proposal was beginning, Frank Luntz—an infamous Republican consultant who specializes in the language of politics—drew up a confidential 28-page report (PDF) for congressional GOPers on how they could confront, and defeat, Obama on this crucial issue. He suggested that they use a particular phrase: “Government takeover of health care.” And they did. Again and again, for the entire months-long debate. During one Meet the Press appearance, Rep. John Boehner (R-Ohio), then the House minority leader, referred to Obama’s plan as a “government takeover” five times (without once being challenged).

It was a clear falsehood. Obama’s system relies on private insurance and the market—especially after he abandoned a public option—albeit with additional government regulation. PolitiFact.com, a fact-checking site operated by the St. Petersburg Times, declared Luntz’s formulation the “Lie of the Year” of 2010. (Luntz didn’t have to make an acceptance speech.) Yet the line stuck. A Bloomberg poll conducted as Congress approved the legislation found that 53 percent of American adults believed it amounted “to a government takeover.” A USA Today/Gallup survey indicated that 65 percent thought the new law would expand government’s role in health care “too much.” Several months later, a Gallup poll found that 10 percent selected “government involvement in health care” as the No. 1 health care problem facing the nation—over access or cost. In 2008, only 1 percent had cited government interference as the top problem.

Though Republicans lost the legislative war, they had Luntzified the debate and won the battle to define the health care measure through a Big Lie. This was significant: It established a foundation for the right’s counterattacks—including the 2010 congressional elections, the ongoing effort to repeal or curtail the law, and the burgeoning 2012 campaign.

So why did two measly words come to bedevil the most powerful man in the world? What could Obama and his crew have done to stop the fabrication from taking root and growing into poison ivy?

“Nobody has the exact answer to that,” says Anita Dunn, who was White House communications director in 2009. But surprisingly, she notes that it’s “much easier” for a presidential candidate to combat disinformation than for a sitting president to do the same—no matter that the latter has the most commanding bully pulpit in the world.

A campaign can call into action allied bloggers, social-media networks, and millions of supporters who share a common and simple goal: to get this guy elected. A campaign can also run paid ads, while a president depends on the conventional media to convey his message. (The Obama presidency was expected to address this handicap by converting the mammoth grassroots effort of the campaign into an ongoing political force—a conversion not effectively realized.)

What’s more, on the campaign trail, the penalty for lying—though not always applied—can be higher. A fib that’s widely exposed can define the public’s view of the prevaricating candidate. That’s much less of a problem for, say, a member of Congress with a safe seat or an advocacy group making a false claim against a White House proposal.

Perhaps most importantly, notes Bill Burton, a former deputy press secretary in the Obama White House, the entire communications operation of a campaign has one aim: Promote the candidate, and defend against untrue assertions. “In government,” he says, “that’s one of many things a communications team is responsible for.” And it’s not a fair fight—even if one side is the White House. “You had monied interests spending $200 million against health care reform,” Burton says. “And we’re up against a million fractured groups and voices.”

So what’s a president to do?

Actually, it’s pretty basic. “First, you have to get as many of your own people as you can muster calling a lie a lie,” says Dunn. “Second, try to get referees, like fact-checking organizations, to weigh in. Third, keep doing it.” She notes that none of this is easy, particularly No. 3: “The press doesn’t want to repeat every day, ‘Look, the Republicans are still lying about it.'”

Of course, the Obama administration and its defenders did all that. They went on cable shows, did newspaper interviews, tweeted and Facebooked, and generally tried, as Burton puts it, to “find every single avenue into Americans’ living rooms.” They cited PolitiFact and other independent sources confirming that the government-takeover line was false. They kept at it for months—make that years. But they couldn’t vanquish the lie.

Dunn recalls that on the day that Obama signed the health care measure into law, she was traveling in Florida and watching local TV. Before the signing ceremony, a local station did a long interview with a GOP congressman. He warned of how horrible this government takeover of health care would be; he complained that taxes would go up and people would not be able to choose their doctors. “We didn’t have anything to counter that,” she says. “The president has a pretty big bully pulpit, but you can’t have him come out on an hourly basis saying, ‘It’s not a government takeover.'”

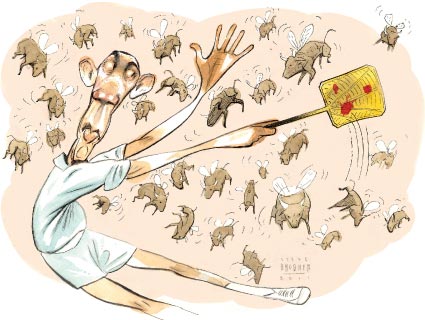

Mark Twain is said to have once quipped, “A lie can travel halfway round the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.” That’s even truer today: “There’s this whole phenomenon of an internet fact,” notes Dunn. “If something is not immediately and vigorously denied, and is repeated over and over, it becomes a fact because it turns up on Google.” Lanny Davis, who did damage control for the Clinton White House (and, recently, himself, when news reports noted that he was working for African tyrants), argues that “search engines take misinformation and put it into an echo chamber. Trying to counter it is the functional equivalent of having your hair full of honey and bees, and you’re trying to whack the bees with your hands.”

Davis recalls an episode in the fall of 1997—pre-Google, but just as the internet was becoming a factor in political communications—when he was working in the White House. A reporter for Insight, a conservative magazine, approached him about a story alleging that President Bill Clinton had arranged for dozens of friends and donors to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, including a contributor who had served as US ambassador to Switzerland. Davis said he would check it out and get back to the reporter, and he contacted the secretary of the Army. The reporter didn’t wait. He posted the article, and it became a right-wing sensation. Conservative talk-show hosts went wild. Congressional Republicans—including House Speaker Newt Gingrich—vowed investigations. The story was locked in: Clinton had sold burial plots in Arlington.

In fact, it turned out, the president had recommended burial waivers for four people, including former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. None were donors, and the ambassador in question was not among them. But it took Davis and the White House two days to sort out the facts. By then, the story had gone global. “I was getting calls from around the world,” Davis says. “We couldn’t do anything at that point, just make sure that the truth was written down somewhere” for posterity. You can’t win in such a situation, he says: “If you’re lucky—and do everything possible—maybe you get to a draw. And that’s if you’re very lucky.”

Republicans are doing their best to ensure that the White House doesn’t reach that level of luck with health care. Earlier this year, after Rep. Dan Lungren (R-Calif.) made a speech on the House floor decrying the health care law, Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) noted that PolitiFact had called the government-takeover accusation the top lie of 2010. Lungren interrupted to request that Blumenauer’s comment be stricken from the record for impugning another member. A small fuss ensued on the House floor; the Republicans were essentially claiming that calling a lie a lie was a lie. After legislators reviewed the remarks, Blumenauer asked to withdraw his own statement because Lungren had not specifically referred to a government takeover this time (though he had in the past). “I apologize if the person who said ‘government takeover of health care’ was not you,” Blumenauer said. “It is repeated so often by my Republican friends, including the speaker of the House, time and time again, that sometimes I get confused.”