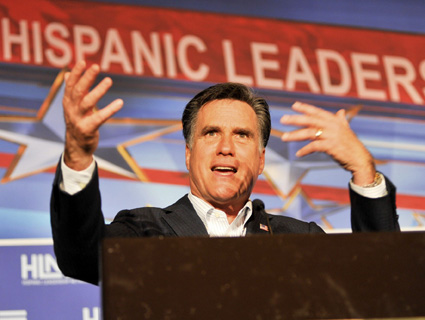

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/davelawrence8/6791949310/">davelawrence8</a>/Flickr

Mitt Romney has a history problem.

It’s not only that past events and stances—say, his implementation of an Obamacare-like reform in Massachusetts, or his 1994 call for “full equality” for gay and lesbians—undermine his current efforts by calling into question his political integrity. Romney often distorts—or is detached from—significant realities of his personal past.

Voters and the media world received a glimpse of this last month when the Washington Post disclosed that Romney, while attending an elite prep school, once led a posse of schoolmates to assault a fellow student who was thought to be gay. Though the newspaper cited five sources, including several participants in the brutal episode, Romney, through a spokeswoman, claimed he had “no memory” of the matter. After the story appeared, Romney, still insisting not to recall the event, apologized for pranks that “might have gone too far.” Yet his lack of recollection was tough to believe, especially given the searing memories the attack had left within others. More important, Romney’s blank-out was in keeping with a pattern of selective and manipulative presentations of his past. He’s not merely a flip-flopper; he’s a self-revisionist.

I. The Father

Romney has a wonderfully colorful and much-storied family past. His great-great grandfather Miles Archibald Romney, an English carpenter, was one of the first Brits to convert to Mormonism. Following the call, Miles immigrated to Illinois. Three generations later—after plenty of family drama intertwined with the rise of the Mormon Church—the Romney family would yield George, Mitt’s father. He would become an innovative auto executive, a well-regarded governor of Michigan (who in 1964 walked out of the Republican National Convention to protest nominee Barry Goldwater’s opposition to civil rights legislation), and a presidential candidate.

On the campaign trail, Romney, attempting to establish some 99-percent cred, has emphasized his gritty and hardscrabble family roots, citing his father. In a campaign appearance in February, Romney repeated a familiar refrain:

My father never graduated from college. He apprenticed as a lath and plaster carpenter. And he [was] pretty good at it. He actually could take a handful of nails, stick them in his mouth and then, you know, spit them out, pointy end forward. On his honeymoon, he put aluminum paint in the trunk of the car and sold it along the way to pay for the gas in the hotels.

Mitt’s father, in this account, was one helluva tough guy with quite a pair of bootstraps, a working-class hero. But that’s not quite what happened. George attended George Washington University in Washington, DC, and while he was a student, according to Michael Kranish and Scott Helman’s fine biography, The Real Romney, George Romney became a typist and then a policy aide for Sen. David Walsh (D-Mass.). He then used his Capitol Hill connections to obtain a job as a salesman for the Aluminum Company of America. He only dropped out of school to chase after Lenore, his sweetheart (and future wife), who had headed to Hollywood to become an actress.

George Romney may have been a good nail-spitter. But he was also a fellow who benefited from inside influence. He parlayed that Senate job into the salesman position, and a few years later, after he had persuaded Lenore to marry him in 1931, George returned to Washington—to become a lobbyist for the Aluminum Company of America. He would later leave that perch and go to work for the Automobile Manufacturers Association.

A carpenter who sold paint, or a well-connected lobbyist? George’s lathing and plastering had little to do with his future success. He had been a Washington insider. But that crucial part of the Romney family biography is excised from Romney’s public memories. (Romney has distorted the past regarding his father in another way, claiming in a 1978 interview, “My father and I marched with Martin Luther King Jr. through the streets of Detroit.” When later news accounts questioned whether this had occurred, Romney said he had meant it as “figure of speech.”)

II. The War

Mitt Romney, who was born in 1947, was eligible for the Vietnam War draft. But he did not serve in the military. In 2007, he told the Boston Globe that he “longed in many respects to actually be in Vietnam and be representing our country there, and in some ways it was frustrating not to feel like I was there as part of the troops that were fighting in Vietnam.” Romney could have acted on that supposed longing by merely signing up—or by not taking steps to avoid the draft. But he chose to duck the war.

In 1994, when Romney was running for the Senate against Ted Kennedy, he told the Boston Herald that he did not “take any actions to remove myself from the pool of young men who were eligible for the draft.” But that’s exactly what he had done.

As the Associated Press recently reported, Romney, while at Stanford in 1965, sought a deferment as a college student. Then for two-and-half years, as he served as a Mormon missionary in France, he maintained a deferment “as a minister of religion or divinity student.” After that deferment expired, Romney again received another academic studies deferment.

That final deferment ran out in 1970, and Romney became eligible for the draft as US troops in Vietnam were decreasing. But his draft number was high, and he was never called.

So his story—he yearned to be fighting for the United States in Vietnam and did nothing to keep himself out of the reach of Uncle Sam—is false. And he has not acknowledged in public a particularly interesting wrinkle. At Stanford, Romney led a protest against demonstrators who mounted an anti-war sit-in at the university. He held a sign that proclaimed, “SPEAK OUT, DON’T SIT IN.” Yet five years later, in 1970, after George Romney had turned against the war, Romney told the Boston Globe, “If it wasn’t a political blunder to move into Vietnam, I don’t know what is.”

Romney wished he could have gone to war, but he didn’t enlist. He took no steps to prevent himself being drafted, but he did. He supported the war, then he didn’t. As a politically-minded son of privilege and politics, Vietnam was a confusing matter for Romney, and he has not addressed that publicly.

III. The Businessman

Why should Mitt Romney be president? He says it is because of his experience as a free-enterprise-loving businessman who has had whopping success in the private sector. On the stump, Romney praises risk-taking entrepreneurial behavior. “What makes America’s economy go is individuals with dreams who take risks, borrow money from their family, max out their credit cards, maybe get an outside investor,” he declared this month. He claims that President Obama doesn’t understand this basic dynamic of the US economy, and Romney suggests that he himself possesses a fundamental appreciation, due to his own biography. At a Republican debate last fall, when Herman Cain challenged Romney’s business record, Romney countered that he had been the CEO of a “start-up.”

Announcing his presidential bid in June 2011, Romney more fully described his role as a private-sector free spirit:

Twenty seven years ago, I left a steady job to join with some friends to start a business. Like many of you, it had been a dream of mine to try and build a business from the ground up. We started in a small office a couple of hours from here and over the years, we were able to grow from ten employees to hundreds.

He was, by his own account, the embodiment of the American spirit: a risk-taking, rugged, go-for-it entrepreneur, willing to sacrifice his “steady job” for a shot at his dream.

Not really. After graduating from Harvard University’s business and law schools—not one, but two citadels of the elite!—Romney rose through the ranks of Bain & Company, a consulting firm. He so impressed Bill Bain, the head of the firm, that Bain asked Romney to oversee the creation of a private equity off-shoot, Bain Capital, which would look to buy up troubled companies, put them in order, and resell them for a profit.

And Romney said no. As recounted in The Real Romney (an essential read for anyone looking to understand the GOP candidate), Romney “saw the opportunity, of course, but he also saw risks.” With five kids at home, he already had a comfortable set-up: great job at Bain & Company, money in the bank. He’d have to kick in some of the start-up funds, and he didn’t want to put his present salary and financial resources on the line. That is, he didn’t leap at the chance to follow his supposed dream of building “a business from the ground up.” His first instinct was to play it safe and not be a daring entrepreneur.

Bill Bain made it safe for Romney. He told the young biz-wiz that if Bain Capital flopped, Romney could have his old job back—and all the salary increases he might have missed. But this wasn’t enough insurance for Romney, who worried his reputation might be tainted should he fail to deliver at the new enterprise. Bain promised that if Romney had to come back to Bain & Company, he’d tell people that was because the consulting firm needed Romney desperately. “So,” Bain later said to Kranish and Helman, “there was no professional or financial risk” for Romney.

Romney was given a golden elevator. And he made the most of it. But his path to becoming a quarter-billionaire is hardly a classic tale of risk-defying entrepreneurship.

Romney’s serial denials of past positions have partly shaped his public political persona. He was for gun control measures, now he’s not. He favored climate change action, now he doesn’t. He was a fan of individual health care mandates, now he decries Obamacare. His craven flexibility was perhaps best epitomized when he tried to explain to Kranish and Helman why during the 1994 Senate campaign he had written a letter to the Log Cabin Republicans, a pro-gay rights group, asserting a desire “to establish full equality for America’s gay and lesbian citizens.” He told the reporters, “well, okay, let’s look at that in the context of who it’s being written to.” Romney, in this moment of candor, was inadvertently admitting he was an unapologetic panderer.

That was an exception. Romney tends to reject charges of flip-flopping, as he did in his unsuccessful interview last November with Fox News’ Bret Baier. And this is to be expected. To be a credible candidate, Romney cannot acknowledge his long list of 180s. (Nor can he dwell on his years as governor of Massachusetts, where his signature accomplishment was health care reform that was the basis for Obama’s initiative.) But his refutation of the past extends beyond the politician’s traditional refusal to acknowledge previous positions that have since become inconvenient. He has adopted an overly flexible attitude toward his personal history, showing that he is an unreliable source of information about himself. If he cannot tell his own tale accurately, can he be trusted to tell the nation’s?