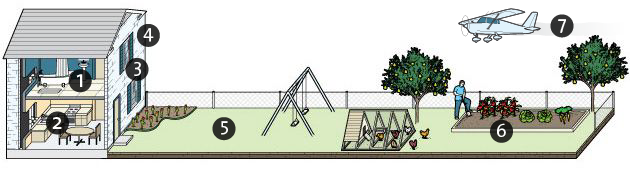

A Cessna 172, which flies with leaded gasoline<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:552GT.jpg">Owen Carroll</a>/Flickr

If you read our magazine cover story on the long, awful legacy of lead in gasoline, you were probably relieved that toxic metal is now banned from all gasoline. The thing is, it’s not.

Some 167,000 piston engine aircraft—about three-quarters of private planes in the United States—are still spewing lead into our air. That’s because their fuel, known as avgas, uses the same tetraethyl lead addictive since banned in automobile gas, making it the No. 1 source of lead emissions in America. (The jet fuel used in big passenger planes does not contain lead.) Lead-free alternatives are available for most piston engine aircraft, but the phaseout of leaded fuel has been slow. Last June, the FAA finally created the Fuels Program Office to replace leaded avgas by 2018—24 years after it was banned in automobiles.

Leaded avgas emits only a small fraction of the lead once coughed out by cars, but it disproportionately affects people living near the 20,000 airports where it’s used. The EPA estimates (PDF) there are 16 million people living within one kilometer of those airports, and 3 million children attend schools in the same radius. According to a 2011 study by Duke University researchers, kids who live near airports have elevated levels of lead in their blood. And as Kevin Drum wrote in his Mother Jones piece, even low blood lead levels have bad health and social consequences.

What’s even more maddening is that a lead-free alternative called mogas—which can be used in 80 percent of exisiting piston engine aircraft—has been available since 1982. The remaining 20 percent of planes can run on mogas with a modification called Inpulse, says Kent Misegades, director of the Aviation Fuel Club.

So why the hold up? Leaded avgas may have flown under the radar for so long precisely because it is a niche market. Without regulatory pressure, there just isn’t enough incentive to change. Flyunleaded.com publishes a list of airports that supply mogas—a list that includes only 3 percent of all airports in the United States, according to Misegades.

Further complicating matters is yet another molecule: ethanol. Neither mogas nor avgas contain ethanol because it can be nasty for plane engines. Ethanol absorbs water from the air, and an ethanol-water mixture corrodes fuel lines, gaskets, and other parts. (Kate Sheppard has also written about the hazards of ethanol for car engines.) However, the EPA’s Renewable Fuel Standard requires more and more ethanol be blended into gasoline until 2022, threatening the supply of ethanol-free mogas. Pilots who want to avoid leaded avgas can buy mogas (available at some gas stations) and bring it to the airport, but ethanol-free mogas is often not available due to the EPA’s fuel standards—leading pilots to rely on avgas.

A couple of environmental groups have taken legal action to speed up avgas’ phaseout. In 2011, the Center for Environmental Health sued several avgas suppliers under California’s Proposition 65, which requires businesses to disclose chemicals that can cause cancer or other health problems. “[The aviation industry] realizes the writing is on the wall,” says CEH spokesperson Charles Margulis. “It’s a matter of time.” After petitioning the EPA to study and regulate aircraft lead emissions in 2006, Friends of the Earth also sued the EPA in 2012 for failing to adequately respond to that petition. A few months later, the FAA announced it would work with the EPA to take concrete steps toward implementing unleaded alternatives.

When leaded avgas is eventually replaced, it will be another small step in the long slog against lead. The health effects of lead in automobile gas were known as early as the 1920s, but it took half a decade century before the EPA moved to eliminate it. Unfortunately, the tetraethyl lead in avgas has been just as stubborn.