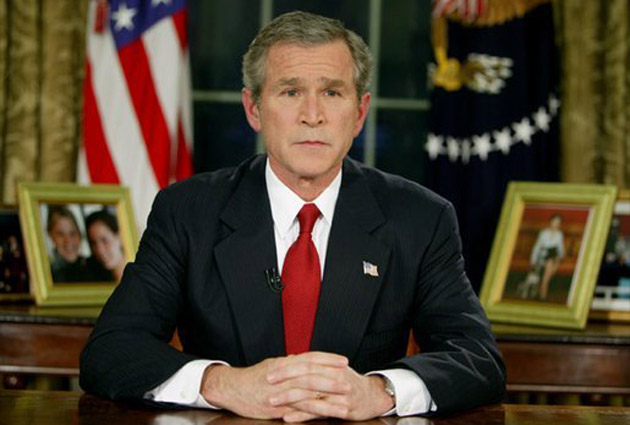

President Bush announcing the invasion of Iraq on March 19, 2003.<a href="http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2003/03/images/20030319-17_address1-515h.html">Paul Morse</a>/White House

One night, more than a decade ago, I was a guest on Bill O’Reilly’s Fox News show along with Bill Kristol, the godfather (or son-of-the-godfather) of the neoconservative movement. The subject: What to do about Iraq? The Bush administration had begun pounding the drums for war, claiming, as Vice President Dick Cheney had put it, that there was “no doubt” tyrant Saddam Hussein was “amassing” weapons of mass destruction “to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us.” As one of the few political analysts on television to question the rush to war, I noted that WMD inspections in Iraq could be useful in preventing Saddam from reaching the “finish line” in developing nuclear weapons. Kristol responded by exclaiming, “He’s past that finish line! He’s past the finish line!”

Saddam wasn’t—as it turned out, he wasn’t even in the race. He possessed no WMD nor any significant program to develop them. And his repressive regime had no meaningful connections with Al Qaeda. Yet in those dreadful months before the March 19, 2003, invasion of Iraq, the cheerleaders for war inhabited a place of privilege within the media. They could say anything—and get away with it. Kristol could declare—as he did the day before our exchange—that a war in Iraq “could have terrifically good effects throughout the Middle East,” face little challenge, and gain plenty of debate-shaping attention.

There was at that time a sort of madness within the political-media world. With the nation still under the shadow of 9/11, prominent journalists had jettisoned the most crucial of traits in our profession: skepticism. At one point, I debated David Brooks, then of the Weekly Standard, over the necessity of launching a war against Iraq. He summed up his support for the endeavor by asking: Don’t you believe the people of Iraq desire democracy just as much as we do?

I was surprised by his naiveté. I was no expert on Iraq, but it was obvious to me that invading and possibly occupying a nation half a globe away could end up rather messy, and that a universal craving for democracy might not trump all else. It seemed to me that Brooks was relying on fairy tale analysis, projecting simplistic assumptions onto an extremely complicated situation. (Sunni, Shiite—how many advocates for war knew the difference?) Yet this was all Brooks needed to champion a war that would cost the lives of nearly 4,500 US troops, injure 32,000 service members, and add $3 trillion to the national credit card—and leave millions of Iraqi civilians displaced and more than 100,000 dead.

A more disheartening moment came when I was talking to a friend who was working for a major newspaper and whom you can now often spot on television. Weeks before the invasion, he acknowledged to me that he wasn’t sure what to make of the Bush administration’s case for war. But he was in favor of invading. Why? Because Tom Friedman, the New York Times columnist, was for it. My friend—an influential voice in the media then and now—had handed Friedman his proxy, and Friedman was all for the war because he believed it would ignite progressive change throughout the Arab/Muslim world.

Friedman, though, had adopted a curious stance. He noted he was “troubled” by how Bush was justifying the war by claiming Saddam was allied with Al Qaeda and observed, “You don’t take the country to war on the wings of a lie.” Yet he was willing to let people he considered liars mount a war—one that would require deft handling and an abundance of judgment to succeed. (The lack of sufficient planning for the post-invasion period was in itself one of the greatest blunders in US history.)

After the invasion, Friedman, now all in, displayed less nuance. In a May 2003 interview with Charlie Rose, he claimed the invasion was a legitimate response to 9/11 (never mind that Saddam had nothing to do with that attack):

What we needed to do was to go over to that part of the world…and burst that [terrorism] bubble. We needed to go over there basically and take out a very big stick, right in the heart of that world, and burst that bubble. And there was only one way to do it…What they needed to see was American boys and girls going house to house, from Basra to Baghdad, and basically saying, ‘Which part of this sentence don’t you understand…Well, suck on this.’

My friend, a smart fellow, was willing to suspend his own critical skills and defer to an influential columnist. That was a common sentiment: The Iraq matter was tough to sort out, and deference ought to be paid to government officials and self-proclaimed experts. There was also a widely shared sense that no one wanted to be caught on the wrong side later on, should a future act of nuclear terrorism be linked to Baghdad. So tying oneself to the mast with Tom Friedman—or accepting Bush and Cheney’s assertions—was safe. If the ship went down, there’d be plenty of cover. You’d be wrong but you’d be in fine company.

Besides, the mass-murdering Saddam was easy to despise, and in Washington there have always been plenty of folks in politics and the media who eagerly await the right war in order to display the kind of toughness that is often associated with leadership. Democrats, in particular, recalled that votes against the first Iraq war—a war generally deemed a success—were subsequently used as political ammunition against them. It was no coincidence that leading Democratic presidential wannabes—John Kerry, Hillary Clinton, John Edwards, Joe Biden, Dick Gephardt—voted in October 2002 for the legislation that handed Bush the authority to launch the invasion.

This tide of war was hard to fight. Most members of Congress had caved during the congressional debate. A few senators and representatives who felt railroaded by the Bush-Cheney crowd—including some Republicans, such as House Majority Leader Dick Armey—nonetheless voted for the measure, against what they later said was their better judgment.

Yet through it all—as Michael Isikoff and I later noted in our book, Hubris: The Inside Story of Spin, Scandal, and the Selling of the Iraq War—there was plenty of information inside the national security agencies—chunks of it uncovered by the few reporters who were doing their jobs—that raised questions about the Bush-Cheney march to war. The Washington bureau of the Knight Ridder newspapers produced a stream of prescient and accurate stories that challenged the Bush-Cheney narrative.

There were other outbreaks of good journalism and challenging commentary. On September 1, 2002, Chris Matthews wrote, “I hate this war that’s coming in Iraq. I don’t think we’ll be proud of it. Oppose this war because it will create a millennium of hatred and the suicidal terrorism that comes with it. You talk about Bush trying to avenge his father. What about the tens of millions of Arab sons who will want to finish a fight we start next spring in Baghdad?” And after the administration began citing a New York Times story (based on information leaked by the administration) that reported Saddam had obtained aluminum tubes to be used to process bomb-grade uranium, the Washington Post published a well-reported article noting that the government’s own experts had questioned this conclusion.

Yet the Post story was buried on page A18 of the paper. It did little to counter White House fear-mongering—such as national security adviser Condoleezza Rice’s hyperbolic statement, referring to those same tubes, “We don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.”

In fact, the overall tone of coverage at many news organizations often overwhelmed the facts reported by those same organizations. When Secretary of State Colin Powell made his now infamous February 5, 2003, appearance at the United Nations to present the White House’s case for war, he was widely lauded on the front pages and network news shows for a bravura performance. Yet buried on the inside of the Post the next day were several stories examining the key allegations in Powell’s speech. Inches into each of them were quotes from experts and intelligence officials disputing Powell’s assertions.

The theatrics triumphed. In an unfortunate column, even the great Mary McGrory noted, “I can only say that [Powell] persuaded me.” (She did qualify, later, that Powell “made the case against Saddam Hussein, but not the case for war.”)

In June 2004, Michael Getler, the Washington Post ombudsman, succinctly summarized the problem: “Too many Post stories that did challenge the official administration view appeared inside the paper rather than on the front page.” He provided a sampling:

“Observers: Evidence for War Lacking; Report Against Iraq Holds Little That’s New,” by Dana Priest and Joby Warrick, Sept 13, 2002; “Unwanted Debate on Iraq-Al Qaeda Links Revived” by Karen DeYoung, Sept. 27, 2002; “U.N. Finds No Proof of Nuclear Program; IAEA Unable to Verify U.S. Claims,” by Colum Lynch, Jan 29, 2003; “Bin Laden-Hussein Link Hazy,” by Walter Pincus and Dana Priest, Feb. 13, 2003; “U.S. Increases Estimated Cost Of War in Iraq; Military Expenses Alone Projected at Up To $95 Billion,” by Mike Allen, Feb. 26, 2003; “U.S. Lacks Specifics on Banned Arms,” by Walter Pincus, March 16, 2003; “Legality of War Is A Matter Of Debate; Many Scholars Doubt Assertion by Bush,” by Peter Slevin, March 18, 2003; “Bush Clings to Dubious Allegations About Iraq,” by Walter Pincus and Dana Milbank, March 18, 2003.

That last article, which was published on the eve of the invasion, is particularly noteworthy. It began:

As the Bush administration prepares to attack Iraq this week, it is doing so on the basis of a number of allegations against Iraqi President Saddam Hussein that have been challenged—and in some cases disproved— by the United Nations, European governments and even U.S. intelligence reports.

This story appeared on page A13 of the newspaper.

As I’ve asked multiple times, how the hell can a newspaper report that the president is leading the nation to war on the basis of charges “that have been challenged—and in some cases disproved” and not splash that story on the front page under a banner headline? The Post deserves no more blame than other major outlets—don’t forget the New York Times and Judith Miller—but the decision to bury this particular story embodies what went wrong.

The Iraq War was a systemic failure. The leaders of the nation used misinformation and disinformation to whip up support for it. Intelligence analysts who knew better were prohibited from speaking out. Members of the legislative branch abandoned their responsibility to vet the misleading claims effectively. (When the administration sent a flawed national intelligence estimate to Congress on Iraq’s WMD program, only a few lawmakers bothered to read it.) And too many reporters and editors, in the wake of 9/11 and the initial US military success in Afghanistan, were reluctant to confront Bush, Cheney, and their lieutenants. This allowed the loud voices for war within the media-commentariat complex to ring out largely unchecked.

Those voices echoed for months and years after the invasion. I vividly recall encountering Christopher Hitchens exiting the Fox News studio on an August day in 2003. He was kind enough to tell me, “Don’t worry about this war. Wolfowitz has the rats on the run. It will all be over soon.” The next day the UN compound in Baghdad was destroyed by a suicide bomb attack.

It took too much time for the swindle to sink in. A year after the invasion, with no WMD in sight, Bush joked about the missing weapons at the annual Radio and Television Correspondents’ Association black-tie dinner—that is, made fun of the reason he sent American soldiers to their deaths and unleashed chaos in Iraq. A crowd of thousands of journalists laughed along with him.

Much of what happened during the Iraq War flimflam is now known and recognized. But those who perpetrated and abetted what Lawrence Wilkerson, Powell’s chief of staff in those days, now calls a “hoax,” generally paid little, if any, price for their mistakes or misdeeds.

Bush and Cheney won reelection, after their political allies swift-boated then-Sen. John Kerry. Powell has become a wise man courted by politicians and the media. Rice retains a measure of star power and was the only Bush-Cheney alum handed a major role at the GOP convention last summer. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was tossed overboard in 2006—someone had to take a fall for the lousy prosecution of the post-invasion war—but his memoir sold well, as did Bush’s and Cheney’s. None of the three expressed any regrets.

Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy defense secretary enthralled with the nutty conspiracy theory that Saddam was the puppet master behind Al Qaeda, was rewarded with a plum: the presidency of the World Bank. (He is now a “scholar” at the American Enterprise Institute.) Douglas Feith, the undersecretary of defense for policy back then, is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute. Neocon commentators, including Kristol, were able to continue unimpeded on their saber-rattling ways, moving on to Iran and Syria. And you know the pinnacle Brooks has reached; he’s left the Standard behind to be a Times opinion-page neighbor of Friedman.

The months preceding the invasion of Iraq were a lonely time in Washington for journalists questioning the justifications for the war, wondering aloud why the Bush-Cheney crowd would not give the WMD inspections under way a chance, and suggesting that there might be alternatives. It was impossible to ensure a serious and somber debate about going to war and the alternatives. Yet though they got the war they craved, the Iraq War crowd has lost the battle over the history.

The war was no self-financing cakewalk, and it is now widely regarded as a mistake, costly in blood and treasure, that was sold to the American public with falsehoods. The invasion did not usher in a progressive era in the Middle East. (Suck on that, Mr. Friedman.) Iraq remains a mess. The Iraq War boosters have moved on to other enterprises and contentions, yet, 10 years later, they have had their assertions measured against reality, and they have been proven wrong and misguided. None of that, though, will bring back the Americans and Iraqis who lost their lives. For when it counted most, the spin worked.