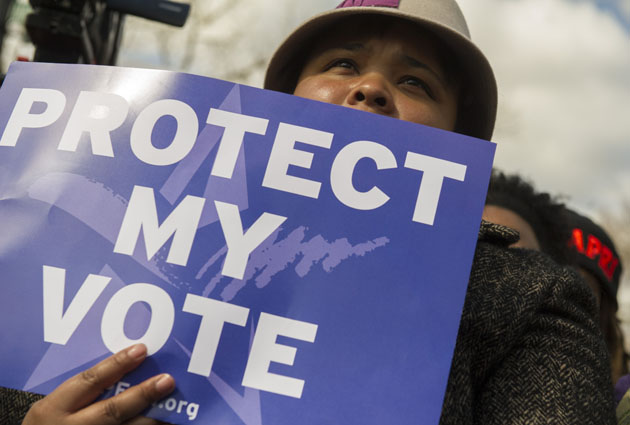

<a href="http://www.zumapress.com/zpdtl.html?IMG=20130227_fil_l112_014.jpg&CNT=5">Rod Lamkey Jr.</a>/ZumaPress

The Supreme Court gutted a key provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act on Tuesday, ruling that the United States had sufficiently moved beyond its Jim Crow past and has rendered the law’s formulas unconstitutional. Writing for the conservative 5-4 majority, Chief Justice John Roberts, who has a long history of trying to undermine this law, struck down Section 4 of the act. This part of the law determines which states and counties must adhere to strict guidelines governing any change to their voting laws. (The point of this provision is to prevent regions that have a history of fiddling with voting laws to discriminate against certain groups from trying such stunts again.)

As proof of the nation’s racial progress, Roberts cited elevated voter registration figures among black voters (setting aside the main issue of whether black voters have the same access to the voting booth once they’re registered) and the fact that civil rights battlegrounds such as Philadelphia, Mississippi, and Selma, Alabama, currently have black mayors.

In the court’s view, the Voting Rights Act has accomplished its mission of squashing racism:

Nearly 50 years later, things have changed dramatically. Largely because of the Voting Rights Act, “[v]oter turnout and registration rates” in covered jurisdictions “now approach parity. Blatantly discriminatory evasions of federal decrees are rare. And minority candidates hold office at unprecedented levels.” Northwest Austin, supra, at 202. The tests and devices that blocked ballot access have been forbidden nationwide for over 40 years. Yet the Act has not eased [its] restrictions or narrowed the scope of [the formula that determines which parts of the country that are covered]. Instead those extraordinary and unprecedented features have been reauthorized as if nothing has changed, and they have grown even stronger.

The basis for Roberts’ argument is that the formula for determining which states, counties, and municipalities warrant special scrutiny under the VRA is outdated. Racism doesn’t exist along a North-South axis as it did in 1965, and Congress is relying on outdated information, Roberts argued. The formula that governs which parts of the country are covered “that Congress reauthorized in 2006 ignores these developments, keeping the focus on decades-old data relevant to decades-old problems, rather than current data reflecting current needs,” Roberts contended. But Roberts, who during oral arguments relied on bungled Census data to assert that Massachusetts has a worse record on voting rights than Mississippi, doesn’t appear to have paid close attention to the data.

In May, political scientists at the University of California-Davis and the University of Connecticut published a study that seemed to anticipate Roberts’ critique, maintaining that “the geography of anti-black prejudice” in the United States closely tracks with the geography of the Voting Rights Act. That is, the states and districts that receive special attention under the VRA because of their histories of discrimination remain the problem areas. (Here’s a handy map from the New York Times that breaks the similarities down.)

The 1965 law has been reauthorized four times, the last time coming in 2006. (It’s set to expire again, barring Congressional action, in 2031.) A congressional report issued at the time—and cited approvingly by Roberts—concluded that if the law wasn’t reauthorized, “racial and language minority citizens will be deprived of the opportunity to exercise their right to vote, or will have their votes diluted, undermining the significant gains made by minorities in the last 40 years.” The act was also upheld by the Supreme Court twice—in 1966 and 1980. The question facing the justices this time was whether the nation had sufficiently evolved to the point where the law’s “strong medicine” was no longer justified.

At the oral argument in February, conservative justices hinted that the answer was no. Justice Antonin Scalia referred to Section 5, the part of the law that requires select states and counties to clear all changes to their elections with the Department of Justice, as the “perpetuation of a racial entitlement.” He also took the unusual step of arguing that the Supreme Court had an obligation to undo the Voting Rights Act because Congress, burdened by political correctness, would be too timid to do so. That led Mother Jones‘ Adam Serwer to declare, with only a small dose of hyperbole, “Supreme Court Poised to Declare Racism Over.” Scalia did not say why such a move would not be considered brazen judicial activism.

In the case before the court, Shelby County, Alabama, the plaintiff, is poorly positioned to claim that Section 5 is an undue burden. Shelby County attempted to redistrict its one African American lawmaker out of a seat in 2006. More recently, in 2011, a Republican state senator was recorded by the FBI calling African Americans “aborigines.” But let’s not pick on Alabama—a three-judge panel ruled last August that under Texas’ rejected redistricting plan, “Anglo district boundaries were redrawn to include particular country clubs and, in one case, the school belonging to the incumbent’s grandchildren”—while African American districts were gutted to become less economically viable.

If Shelby County believed it was being punished unnecessarily, it had recourse. Section 5 is a strict policy, but it’s not impossible to get out of. States and counties can petition to be removed from the list, if they demonstrate sufficient progress over a 10-year period. So far, some 200 districts have been removed from the law, including large swaths of Virginia. (By that same measure, a district can also be added to the list.)

“[V]oting discrimination still exists; no one doubts that,” Roberts wrote in his opinion. But, as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg exclaimed in her blistering dissent, Roberts was by his own admission helping to wipe out one of the most powerful antidotes to discrimination.

You can read Roberts’ and Ginsburg’s opinions here: