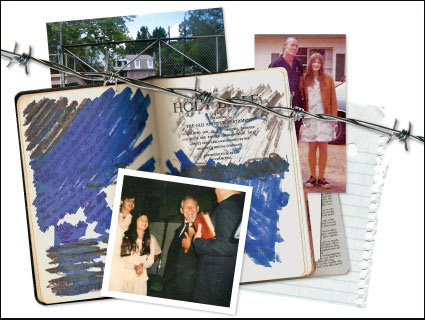

In early August, a few weeks before forensic scientists began exhuming dozens of unmarked graves at the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys, five older black men took a road trip to Marianna, a rural town on the Florida panhandle—historic Klan country—to confront their demons on the reform school’s vast, wooded campus.

Residential cottages on the “black side” of the Dozier campus, which stayed segregated until 1967.

At least 96 children died at Dozier between 1914 and 1973, according to school records, and while state officials say there’s no proof, former students insist that some of the deaths were the result of foul play. Boys of all races were routinely, brutally, and even fatally beaten by staff, they allege; some were raped, and “runners” were fired upon—at least seven kids were reported dead after trying to escape.

Tens of thousands of boys passed through Dozier’s gates between its founding in 1900 and 2011, when Florida officials shut it down (citing budgetary reasons) amid a Justice Department investigation that found ongoing “systemic, egregious, and dangerous practices” at the school.

At a state hearing last August, after years of agitating by former Dozier boys, researchers from the University of South Florida got permission to unearth bodies from the grounds and run tests to determine who those boys were—and how they died. Last month, the scientists came out with an announcement that was disturbing, if not surprising. They had excavated 55 sets of remains at Dozier’s Boot Hill cemetery, 5 more than they’d originally identified, and 24 more than were indicated in the school’s official records. Other campus locations remain to be searched.

A few days before attending the 2013 hearing in Tallahassee, the five men returned to Dozier to call attention to stories from the “black side” of the once-segregated campus—stories they felt were being overlooked, despite all the news coverage. They hadn’t seen the place in a half century or so. Photographer Nina Berman joined them on their road trip to Marianna, and accompanied some of the men into the dilapidated cottages where they’d lived during their time there.

“Every morning before we went to work or school or wherever, you had to line up, and Mr. Crockett inspected you personally,” 67-year-old Richard Huntly recalls. “Standing there in one of the cottages, I could see him coming down the line: ‘Open your mouth!’ you know? Stand back and look at your shoes—‘Smile!’ And if you missed a point, he would brush your teeth for you, and when he brushed them, you didn’t like it.”

Johnny Gaddy, 68, still remembers his first glimpse of the grounds as a child. “This was the most beautiful place you ever seen. They had palm trees in a row. Perfect palm trees,” he says. “It looked so beautiful, but I found out on the black side where began my hell.”

The men came across some old graffiti. Huntly found a shoe like the kind he used to wear.

“The setup was pretty much the way it was when I was a little boy,” says 61-year-old John Bonner. “I was thinking of how it was to be locked away in a dorm at night with so many boys overcrowding us, and you’re scared…You know the staff was capable of doing things to you, and the bigger boys were trying to take advantage of you. And at the time I was thinking about the boys that didn‘t make it out, or the boys who were abused and weren’t able to stand up for themselves.”

The boys were disciplined in a building known as the White House. “We had to call it a ‘spanking,’” Gaddy says, recalling one of his trips there. Mr. Mobley “told me to lay on the bed. There was like a military bed and it had a rail, and I had to grab the rail and hold that bed. And when he hit me, I had never experienced a lick like that in my life. And I prayed to God, Mama, whoever would come and help me out of this predicament. When he hit me, I jumped up. And he said, ‘Boy, if you don’t get back on that bed, I’ll kill you right now!’ He had a belt that had holes in it, and every time he would hit me, it would suck the skin from my behind. All the boys would know you’re bloody from the waist down. All they’d ask: ‘Well? Did you hold the bed?’”

Dozier was unforgiving whatever your skin color. But the white kids were given vocational work while the blacks did grunt labor. (The school profited from both.) “It was brutal work,” Huntly says. “We were out there in the cold cutting cane and planting peas and pulling corn. I was admitted to the third grade when I was there, and I spent two years and about four months there, and the day I left I was still in the third grade. So that’s the kind of education I got.”

“On the white side, it was more roomy. You had the industrial shops, the woodworking shop—places the white boy was able to get a certificate,” Bonner says. “The black side was the slave side.” (Archival photos from State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.)

Gaddy’s job was to haul trash to the black side for burial. “One time, I saw a boy’s hand in the garbage, ” he says. “I asked, ‘What’s a hand doing in there?’ And a boy said, ‘Don’t ever mention that to nobody, because you can end up like that.’ So I didn’t mention it to nobody. I was at the hog pen and I saw a foot in the slop. By that time, I knew not to mention it.”

Gaddy still doesn’t understand how he landed at Dozier. When he was 11, the police showed up at his front door. “They told me the judge wanted to talk to me,” he recalls. “I’ll never forget it as long as I live. I was watching The Lone Ranger on TV. My mama said, ‘The officer going to take you down, the judge going to talk to you.’ I said, ‘Mama, why’s he going to talk to me?’ She said, ‘Go ahead.’ He took me to the police station, told me to get in a cell. I never saw a judge. I wasn’t sentenced for anything as far as I know. I was handcuffed all the way to Marianna.”

Huntly and his brother Arthur, then 11 and 12, were sent there for truancy. Bonner says he was picked up in a ‘well-to-do’ neighborhood and accused of a break-in he insists he had nothing to do with. Hiring a lawyer was out of the question: “The only thing in the courtroom that was black was the judge’s robe and myself.”

On the day of their visit to the grounds, the men held a press conference—which few attended. All in all, it was a painful trip, but they have found solace, at least, in the knowledge that they’re not alone. “When I left Marianna,” Huntly says, “I was thinking that there wasn’t anybody in the world feeling the way that I felt, being taken away so young, being dogged at, being beat the way I was—just a natural slave. But by talking to other guys that went through the same thing, and by going on the grounds at Marianna, I think I’m more prepared to face a lot of things.”

“It’s been very therapeutic for me and my family,” Bonner says, “to meet these guys who had the same experiences, the same nightmares and memories.”