—By Shane Bauer, Josh Fattal, and Sarah Shourd | March/April 2014 Issue

SHANE

The nightmare began on July 31, 2009. I was living in Damascus, covering the Middle East as a freelance journalist, with my girlfriend, Sarah Shourd, a teacher. Our friend Josh Fattal had come to see us, and to celebrate, we took a short trip to Iraqi Kurdistan. The autonomous region—isolated from the violence that wracked the rest of Iraq—was a budding Western tourist destination. After two days of visiting castles and museums, we headed to the Zagros Mountains, where locals directed us to a campground near a waterfall. After a breakfast of bread and cheese, we hiked up a trail we’d been told offered beautiful views. We walked for a few hours, up a winding valley between brown mountains mottled with patches of yellow grass that looked like lion’s fur. We didn’t know that we were headed toward the worst 26 months of our lives.

JOSH (July 31, 2009)

“You guys,” Sarah says with hesitancy. “I think we should head back.”

“Really?” Shane sounds surprised. “How could we not pop up to the ridge? We’re so close.”

Shane knows I want to reach the top. “Josh, what do you want to do?” he asks.

“I think we should just go to the ridge—it’s only a couple minutes away. Let’s take a quick peek, then come right back down.” Just as we’re setting out, Sarah stops in her tracks. “There’s a soldier on the ridge. He’s got a gun,” she says. “He’s waving us up the trail.” I pause and look at my friends. Maybe it’s an Iraqi army outpost. We stride silently uphill. I can feel my heart pounding against my ribs.

The soldier is young and nonchalant, and he beckons us to him with a wave. When we finally approach him, he asks, “Farsi?”

“Faransi?” Shane asks, then continues in Arabic. “I don’t speak French. Do you speak Arabic?”

“Shane!” I whisper urgently. “He asked if we speak Farsi!” I notice the red, white, and green flag on the soldier’s lapel. This isn’t an Iraqi soldier. We’re in Iran.

The soldier signals us to follow him to a small, unmarked building. Around us, mountains unfold in all directions. A portly man in a pink shirt who looks like he just woke up starts barking orders. He stays with us as his soldiers dig through our bags. His eyes are on Sarah—scanning up and down. I can feel her tensing up.

I keep asking, “Iran? Iraq?” trying to figure out where the border lies and pleading with them to let us go. Sarah finds a guy who speaks a little English and seems trustworthy. He points to the ground under his feet and says, “Iran.” Then he points to the road we came on and says, “Iraq.” We start making a fuss, insisting we should be allowed to leave because they called us over their border. He agrees and says in awkward English, “You are true.” It’s a remote outpost and our arrival is probably the most interesting thing that has happened for years.

The English speaker approaches us again after talking to the commander. “You. Go,” he says. “You. Go. Iran.”

SHANE (August 2, 2009)

Beneath the night sky, the city is smearing slowly past our windows. Who are these two men in the front seats? Where are they taking us? They aren’t speaking. The pudgy man in the passenger seat is making the little movements that nervous people do: coughing fake coughs; adjusting his seating position compulsively. Everyone in the car is trying to prove to one another, and maybe to ourselves, that we aren’t afraid.

But Sarah’s hand is growing limp in mine. Something is very wrong.

“He’s got a gun,” Josh says, startled but calm. “He just put it on the dash.”

“Where are we going?” Sarah asks in a disarming, honey-sweet voice. “Sssssss!” the pudgy man hisses, turning around and putting his finger to his lips. The headlights of the car trailing us light up his face, revealing his cold, bored eyes. He picks up the gun in his right hand and cocks it.

Sarah’s eyes widen. She leans toward the man in front and, with a note of desperation, says, “Ahmadinejad good!” (thumbs up) “Obama bad!” (thumbs down). The pistol is resting in his lap. He turns to face us again and holds both his hands out with palms facing each other. “Iran,” he says, nodding toward one hand. “America,” he says, lifting the other. “Problem,” he says, stretching out the distance between them.

Sarah turns to me. “Do you think he is going to hurt us?” she asks. I don’t know whether to respond or just stare at her.

In my mind, I see us pulling over to the side of the road and leaving the car quietly. My tremulous legs will convey me mechanically over the rocky earth. I will be holding Sarah’s hand and maybe Josh’s too, but I will be mostly gone already, walking flesh with no spirit. We won’t kiss passionately in our final moments before the trigger pull. We won’t scream. We won’t run. We won’t utter fabulous words of defiance as we stare down the gun barrel. We will be like mice, paralyzed by fear, limp in the slack jaw of a cat.

Each of us will fall, one by one, hitting the gravelly earth with a thud.

Sarah pumps Josh’s and my hands. Her eyes have sudden strength in them, forced yet somehow genuine. “We’re going to be okay, you guys. They are just trying to scare us.”

JOSH (August 4, 2009)

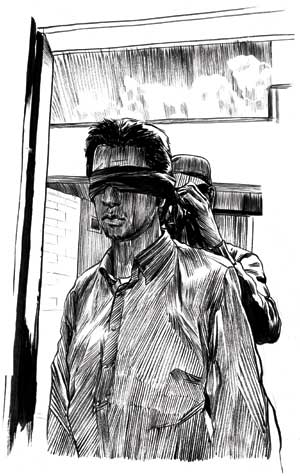

My sandals clap loudly on the floor as I try to catch my momentum and keep my balance. After every few steps, they spin me in circles. My mind tries desperately to remember the way back.

The door shuts behind me. The clanging metal reverberates until silence resumes. I stand at the door, distraught and disoriented. Whatever script, whatever drama I thought I was in, ends now. Whatever stage I thought I was on is now empty. I dodder to the corner of my cell and take a seat on the carpet. There is nothing in my 8-by-12-foot cell: no mattress, no chair—just a room, empty except for three wool blankets. My prison uniform—blue pants, blue collared shirt—blends with the blue marble wall behind me and the tight blue carpet below.

Shane and Sarah are probably sulking in the corners of their cells too. We agreed we’d hunger strike if we were split up. Now I don’t feel defiant. I just feel lost.

Sarah’s glasses are in my breast pocket. She gave them to me to hold when they made us wear blindfolds. She didn’t have pockets in her prison uniform—they dressed her in heaps of dark clothes, including a brown hijab. I empty my other pockets: lip balm from the hike and a wafer wrapper—the remnant of my measly lunch.

I don’t know what I’ll do in here for the rest of the day. I sense the hovering blankness—a zone of mindlessness that looms over my psyche and lives in the silence of my cell.

SARAH (August 6, 2009)

“Sarah, eat this cookie.”

“Not until I see Josh and Shane.”

I’m sitting blindfolded in a classroom chair. A cookie is on the desk in front of me.

“Do you think we care if you eat, Sarah?”

They do care. I know that much. I’ve been on hunger strike since they split us up two days ago. At first it was difficult, but I’m learning how to conserve my energy. When I stand up, my heart beats furiously, so I lie on the floor most of the day. Terrible thoughts and images occupy my mind—my mom balled up on the floor screaming when she learns I’ve been captured, masked prison guards coming into my cell to rape me—but I’ve found ways to distract myself, like slowly going over multiplication tables in my head.

“Sarah, why did you come to the Middle East to live in Damascus?” the interrogator asks. “Don’t you miss your family? Your country?”

“Yes, of course I do. But it’s only for a couple of years. I can’t believe you’re asking me this—do you realize how scared and worried my family must be? Why can’t I make a phone call and tell them I’m alive?”

There are four or five interrogators. The one who seems like the boss is pacing and talking angrily in Farsi. They tell me if I eat their cookie, I can see Shane and Josh.

“Let me see them first—then I’ll eat.”

“Sarah, you say you are a teacher. Have you ever been to the Pentagon?”

“No, I’ve never even been to Washington, DC.”

“Please, Sarah, tell the truth. How can you be a teacher, an educated person, and never go to the Pentagon? Describe to us just the lobby.”

“I’ve never been to the Pentagon. Teachers don’t go to the Pentagon!” I almost have to stop myself from laughing, partly because I’m weak from not eating and partly because I can’t really convince myself this nightmare is real.

JOSH (August 18, 2009)

In my mind I am already running. My feet patter quickly on the brick floor. All day, my energy is dammed up, but in the courtyard, energy courses through me. They take me for two half-hour sessions per day. I’m allotted a single lane next to other blindfolded prisoners. It’s the only time I feel alive all day—when I’m out here and thinking about escaping.

Once, when I heard a helicopter whirring near the prison, I deluded myself into believing freedom was imminent. I decided US officials must be negotiating our release and that I’d be free within three days. Now I cling to the idea of being released on Day 30. In the corner of my cell, the corner most difficult to see from the entryway, there are a host of tally marks scratched into the wall. I check the mean, median, and mode of the data sample. The longest detentions last three or four months, but most markings are less than 30 days. I remember an Iranian American was recently detained and released from prison. How long was she held? Thirty days seems like a fair enough time for the political maneuvering to sort itself out.

JOSH (August 30, 2009)

Suddenly, the metal door rattles. A guard signals me to clean my room and gather my belongings. I am prepared for this. The floor is already immaculate—sweeping the floor with my hands is one of my favorite activities. I grab my book and three dried dates stuffed with pistachio nuts to share with Sarah and Shane. I wasn’t crazy. Day 30 is for real.

When we’re in the car, I can hardly control my joy. I turn to Shane and Sarah, and we start giggling—nervous laughter—at the comfort of our companionship. Now that we’re together again, the weeks of solitude I’ve just endured seem like a distant memory. Was it really a month? Somehow this is funny to us.

Sarah tells me that she and Shane spoke to each other through a vent. They what? Sarah says, “I promise we didn’t do it much.” I can’t believe they were near each other. They had each other! I had nothing.

These guys don’t have a clue what I experienced. I would have done anything for a voice to talk to. I push the idea of them talking as far from my mind as possible, trying to convince myself of what I’d always assumed—we are in this together.

In the rearview mirror, I make eye contact with the stoic driver.

He slows to a stop, then lifts the emergency brake. His gaze, knowing and pitiless, conveys the truth. Shades and bars cover every window of the dirty, gray building before us. This is another prison.

JOSH (September 2, 2009)

In this prison, guards don’t hide their faces like they did in the last one. Some even talk to me. One guard, who speaks a little English, taught me the Farsi word for the courtyard we go to, hava khori. He told me that it literally means “eating air.”

I’ve even grown friendly with a guard I call “Friend.” I treated him amiably and he has responded in kind. He speaks awkward English and tries out colloquial expressions on me. He makes small talk, which can be the most significant event of my day. Friend gave me a bed and mattress, pistachios, bottled water, and crackers. He even gave me a small personal fridge that he put in the hallway in front of my cell. With snacks in front of me, I allowed myself to feel how hungry I’ve been, and how my stomach shrank after 11 days of hunger striking and four weeks on a prison diet.

Friend shows up at my cell to escort me down the hallway to hava khori. “Do you know what a honey is?” He smiles goofily. “Do you have a honey?” “No,” I say dismissively, “and I don’t want a honey in here.” I regret talking to him about English expressions. Why is he asking me about a honey? Why did he give me a bed last week? I push away the thought these questions raise.

SHANE (October 2009)

Solitary confinement is the slow erasure of who you thought you were. You think you are still you, but you have no real way of knowing. How can you know if you have no one to reflect you back to yourself? Would I know if I was going crazy? The longer I am alone, the more my mind slows. All I want to do is to forget about everything.

But I can’t do it. I am unable to keep my mind from being sharply focused on one task: forcing myself not to look at the wall behind me. I know that eventually, a tiny sliver of sunlight will spill in through the grated window and place a quarter-size dot on the wall. It’s ridiculous that I’m thinking about it this early. I’ve been awake only 10 minutes and I should know it will be hours before it appears.

They take everything from us—breezes, eye contact, human touch, the feeling of warm wet hands from washing a sink-load of dishes, the miracle of transforming thoughts into words on paper. They leave only the pause—those moments of waiting at bus stops, of cigarette breaks. They make time the object of our hatred.

I try not to look for the light.

Eventually, I pull myself up and out of bed. I take the few steps to one end of the cell, then back to the other. For a while, I had a few books to transport me out of this prison. The interrogators gave us Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Edith Hamilton’s Mythology, the Persian poet Ferdowsi‘s Shahnameh, and—without irony—Orwell’s Animal Farm. But recently, they took them all away. Now I just have Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. I recently memorized “To the Garden the World,” so I recite it over and over again as I pace, jutting my finger into the air at the line “Curious here behold my resurrection after slumber.”

As I walk, my finger taps against my thigh in alternating short and long pulses, each accompanied by high-pitched vocal beeps. I recite the poem in Morse code, tapping out the lines, “By my side or back of me Eve following,/Or in front, and I following her just the same.” I’ve been studying Morse code in the dictionary Sarah convinced the interrogators to give us by saying she wanted to learn it like Malcolm X did when he was in prison. We take turns with it for a week at a time, passing it to one another through our interrogators.

Somehow the study of Morse code seems useful to me. It makes me feel like my life isn’t seeping down the drain for nothing. Maybe someday I’ll be stranded somewhere with a flashlight and will be able to code my way to safety. Actually, I know that’s bullshit. I study Morse code because I need challenges like this to survive.

I slide under my bed on my back and lift the end as though it were a bench press. I do sit-ups and pushups. I jog in place on a stack of blankets and do high head-kicks back and forth across the cell. I give myself a sponge bath in the sink and look at the wall again. The light is there now—a trickle of diagonal dots. The day has begun. I am hopeful that today my interrogator will come. Then, at least, I will have some human contact.

After lunch, the hours pass blankly until the light is on the long wall. The two large rectangles of 10 vertical bars of light have fully gone around the corner. The day is at its midpoint. My interrogator isn’t coming. He never comes after lunch. All that’s left of the day is stagnation. All I can do is wait for sleep. I’ve already juggled oranges and swept the floor clean with my hands. I do make one discovery: The color red is absent from my life, but if I close my eyes and put my face in the patch of sun, I can see it.

Then, still pacing, I start thinking of books. The titles comfort me: The Brothers Karamazov, War and Peace, A People’s History of the United States. I’m afraid that when the time comes to tell somebody what books I want, I will forget one, so I recite them occasionally to remember. I know that if that opportunity arises, I will only have one chance. I’ve decided to keep a list of 10. Why 10? I don’t know.

Eventually I realize how quickly I’m bouncing from one end of the cell to the next. I’m not walking so much as striding. And I’m speaking out loud. I stop and look around. How long have I been doing that, repeating these titles out loud and counting them on my fingers? Something about realizing that I’ve been hearing my own voice—merely hearing it, not commanding it—frightens me.

SHANE (November 2009)

At the end of each hallway, there’s a small open-air cell. The guards sat me in one of those today. I’ve been in here, listening to Sarah’s voice in a nearby room for a while now. “You have to let me call my mother!” she is shouting. “You can’t do this!” Her cries sound desperate.

I am boiling inside. What are they saying to make her wail like that? The interrogators haven’t come to me yet, but these sounds are making me nervous. We were caught a week ago using illegal pens and leaving notes at hava khori for one another to find. Ever since then, I’ve been waiting for them to come.

An interrogator comes in. He’s the tall, oafish one I sometimes hear speaking to Sarah while she is being interrogated. He is always telling me not to worry about her, that she is doing wonderfully. “You are stupid, Shane,” he says. “What did you think you were doing?” He comes in close behind me. “Stupid!” he says again, smacking me on the back of the head, not hard, just a humiliating slap that brings alive in me something reminiscent of all those school bullies who slapped, punched, kicked, and choked my younger, smaller, bespectacled self.

I jump out of my seat, pull my blindfold off, and spin around to face him. He is towering over me, at least a foot taller than I am.

“Don’t you ever touch me like that again,” I say, pointing my finger toward his face. I don’t remember the last time I’ve been swept away with such heat.

His jaw lowers and his square, pale face goes cold. He looks frightened, not frightened that I will hurt him—he’s huge—but frightened that he made some mistake. The slap felt routine, like something he does all the time. But we are high-value prisoners. He can’t do this with us. He knows that, but until now, I don’t think he knew that I knew that. I’m not quite sure why I do.

“Okay,” he says, almost placatingly. “I won’t do it again.” I hold his gaze for a second longer than is comfortable, his eyes dripping remorse, mine full of fire.

Slowly and self-assuredly, I turn around, sit down, and begin to write: “I had a pen. I knew it was illegal, but I did it anyway. I needed to communicate with Sarah and Josh. It was a moment of weakness. It was a mistake and I will never do it again. If I do, I accept full punishment. I hope you find it in your heart to forgive us and to give us another chance.”

I know that I have no choice. The interrogators can always punish me by punishing Sarah and Josh.

SHANE (December 8, 2009)

A guard is at my door. He is smiling slightly, which I’ve never seen him do. He takes me to the door of a cell with a fridge—an object I know to be the privilege of only a few prisoners—next to it. He opens the door and there is Josh, genuflecting with his head on the ground. He jolts up, looking stunned. “What’s going on?” he says.

“It looks like I’m moving in,” I reply. He leaps up, and we hug and laugh. The guard is now smiling widely. The cell door closes behind us.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen each other recently. For the past 10 days, they’ve been allowing the three of us to meet for half-hour sessions at hava khori. These meetings have been mostly frantic, each of us desperately trying to unload what we’ve been storing in our minds for months.

Now, in a cell together, Josh and I come back to life. After five months of isolation, the possibility of conversation on any topic for any length of time is overwhelming. We talk about The Idiot to an absurd extent, reading passages at random to discuss them as though they were Scripture. Josh gives me a lesson on the musical career of Bob Dylan and I school him on the Balkan Wars. Since we aren’t allowed pens, I draw an invisible map with my finger on the wall.

Josh tries to remember the Hebrew alphabet. He teaches me the letters by writing them with sunflower seeds. The task becomes stressful because we have to destroy the letters every time we hear footsteps, lest we give the guards “evidence” that we are Israeli spies. We stay up late at night and discuss Josh’s ideas about the city government in Cottage Grove, Oregon. We make lemonade with the lemons from our lunch. We shoot hoops with a wad of paper and an empty box. We draw a ring on the floor and see who can toss the greater number of candies inside it. We say “Good night” to each other before we go to sleep.

On our first day together, we come out to hava khori to find Sarah. “Guess what?” I say. “Josh and I are in the same cell now.” I can barely contain my excitement.

She takes a deep breath. “It’s okay,” she says.

The next day, Josh stays behind so I can be alone with Sarah for the first time in months. When I pull my blindfold off, I see her at the opposite end of the courtyard, hunched over and staring at me with cold, angry eyes I barely recognize. I rush over to her and she steps back, like a cowering animal. For every advance I make, she makes a retreat, scowling. Then, her frigid eyes begin to tear. “It’s not fair, Shane,” she whimpers.

“I know, baby,” I say, reaching my hand out. “It’s not fair.” I step toward her again.

As soon as I touch her, she starts screaming, kicking and punching the wall with each word. “It’s! Not! Fair!”

I throw my arms around her as she tries desperately to pull away from me.

“It’s okay, baby,” I say. In my mind I’m saying these words softly, trying to soothe her pain, but in fact I’m shouting, competing with her screams. “It’s okay! Sarah. Stop! It’s okay.”

“It’s okay?” she says sharply, looking at me like I’ve just smacked her. “It’s not okay, Shane. This is not okay!” She’s right, of course. It’s not okay that she is alone and I am not. But I don’t know what else to say.

Eventually, her rage shifts into sorrow. She lets me hold her. But it doesn’t feel like she has found comfort. It feels like something is fundamentally broken, in me, in her, between us. I feel like an accomplice in torture.

What if they’d asked me if I wanted to cell up with Josh? Would I have refused? If I could have, should I have? Every time I laugh or share a meal with Josh or stay awake longer than I would if I were alone, part of me feels like I’m turning my back on Sarah.

SARAH (December 12, 2009)

Fuck you, body, I think as I get out of bed. My head is a balloon filled with water, my shoulders are slack and lifeless, and my eyes feel like glass. I slowly pull on my pants, walk three steps to the sink, and drink two cups of water. My stomach makes an ugly sound, so I ring the bell for the second time even though I know it won’t make the guards come any faster.

The bell is a round, black rubber button on the wall. When I push it, a green light, which the guards can see but often ignore, comes on outside my cell door. I need to use the bathroom, so I begin to pace the length of my 10-by-14-foot cell, punching the air like a boxer with my eyes fixed on my bare feet and the brown carpet. I let out a cry of frustration, pick up a plastic cup, and hurl it at the wall. I decide to pee in the sink.

Ever since I found out Shane and Josh were put together, I’ve been full of uncontrollable anger at everything and everyone. And hate—an almost violent hate.

If Shane and Josh can get through this, so can I. That’s been my motto since we came here. Even during the months we didn’t see each other, I knew they were enduring the same empty hours I was. Now that they are together in one cell, there’s a rupture between us, a distance I don’t know how to bridge.

When I’m with Shane and Josh in hava khori, I almost feel worse. Every touch reminds me of the absence of touch. Their situation seems heavenly to me—they’re out of solitary! What could be better than sharing a leisurely game of chess, listening to endless stories about each other’s lives, being able to connect without the fear of interference? They are halfway there, halfway to sanity and normalcy, halfway to freedom! I want to feel happy for them, but I don’t know how much longer I can hold it together alone in this cell.

These symptoms scare me. Sometimes when I try to read, I can’t focus and end up reading the same line again and again, finally hurling my book in frustration. I’ve become extremely paranoid about my stuff, afraid the guards will take things when I’m gone. I hide the food and other junk I hoard all over my cell—under the carpet, in my mattress—and check it compulsively.

How will I know when I’ve left sane thought and behavior behind? When there’s no turning back? I’ve always clung to the certainty that I can emerge from this place unbroken and unchanged, but I’m not sure I believe that any more. Why am I being singled out for this torture? How can they leave me in here to go crazy alone?

Suddenly I’m on my feet, running to the door. I start banging on it with my fists, kicking it again and again. The guard opens the door and I stare at her, breathless and angry, my hands balled into fists.

“I want hava khori,” I demand, my voice trembling, my face locked.

“No, Sarah!” she yells. “No hava khori today!” I hear the door slam. I hear her footsteps running down the hall. I don’t hear anything else. I want to die. I want to disappear. I want to kill.

I hear a scream. It’s far away, maybe in the courtyard or the next row of cells. There’s something familiar about it.

The door opens and a guard is in my cell. She looks at me with horror and through her eyes I see myself. The scream I heard wasn’t coming from down the hall. It came from my own throat.

The guard grabs my shoulders, and begins to shake me. “Sarah, no! Sarah, no!” We fall to the floor, and I can feel her hands on my face. I open my eyes and follow her gaze to the wall. I see streaks of blood against the mottled white. I look down at my hands and begin to wail like a child. My knuckles are scraped from where I’d been beating them against the wall.

“I can’t!” I yell at her. “I can’t do this.” Her arms encircle me now. “I can’t!”

SARAH (December 27, 2009)

The guards in the hall are frantic as they lead us back to our cells from hava khori. I peek under my blindfold as we pass five or six young women lined up facing the wall. It’s evident by their fitted jeans, long black jackets, and platform shoes that they’ve just been brought in from the streets. I sense their fear as I’m led past. One has a bandage wrapped around her head, caked with blood. Another is limping, her bright red hair streaming out of her torn headscarf. Based on the number of new women I’ve seen, I estimate there are now 10 or 12 packed into each cell.

I’ve had a hunch something like this might be coming. When I woke up this morning, the guard who brought me breakfast was uncharacteristically brisk. Then I heard helicopters circling outside my cell window. After my screaming episode two weeks ago, my interrogators attempted to pacify me by placing a small TV and DVD player in my cell. I’ve watched the one movie they gave me, the 2008 presidential assassination drama Vantage Point, about 18 times now, and I spend hours each day reading the English ticker on the Farsi news channel. This week, thinly veiled threats against “hooliganism” on the news caught my attention. Then boxes of new prison uniforms and plastic slippers arrived at the end of the corridor. I assumed the “Green Revolution” protests we watched on TV in Damascus last spring were over, but the government-controlled media has been gearing up for something for weeks.

I decide to ring for the guard and ask for my nightly shower. “Nah,” she says, exasperated, “kaar daaram.” I’m busy. I begin to pantomime, performing like a trained monkey, smelling my armpits and crinkling up my nose.

“Okay, enough, Sarah, quickly!” I grab my towel, hastily tie my blindfold around my head, and charge down the hall toward the showers.

I crank the hot-water knob as high as it will go, steaming up the room like a sauna. Is it really a revolution this time? If this government’s overthrown, what will happen to us? Things could get really ugly before the opposition assumes power. We could get hurt, separated, or killed in the interim.

I suddenly hear the door open in the small room next to the showers. I quietly unlatch the barred window, peering into the small courtyard. A young woman stares back at me.

Think fast, I tell myself. It’s been several months since one of the guards has made such a slip, leaving me alone in the bathroom with another prisoner nearby. I grab the bars between us, bringing my face as close to hers as I can. “I Sarah. American. Long time here, no freedom,” I whisper in my ridiculous, infantile Farsi. “You please phone mother Sarah. Sarah no spy, Sarah love Iran people, Sarah teacher, Damascus. Please you freedom phone mother Sarah, okay?” The woman looks straight at me. “I know you, Sarah,” she says in awkward but good English. “I am sorry, but I am not free, so I cannot help you.”

At that moment the door opens and a guard starts yelling at both of us. She hands the prisoner a stack of navy blue clothes and ushers her down the hallway.

SHANE (Early January 2010)

Little cakes and candies wrapped in cellophane dash across the cell floor. The disruption freezes me momentarily as I kneel over tiny flash cards, each displaying a name, arrayed in a large network on the carpet. I was in the middle of something important: constructing an elaborate Greek family tree of gods and mortals. I’d been frustrated because I couldn’t remember which marriages connected the House of Atreus to the House of Thebes. How many days must I study this before it finally sticks? It takes me a moment to realize that the sweets were tossed in through the window in the door. Josh and I lunge to the floor and rip open some cakes. We each put a morsel into our mouths, chewing slowly with our eyes closed. It’s spongy, like a Twinkie. The concentrated blast of sugar is like an injection of well-being.

After we finish, we set to work splitting open some dates, removing the pits, and pressing some dark chocolate and a glob of butter into each of them. We put six of these in a small plastic bag that I put in my pocket. Later, a guard comes to take us to hava khori. As I pass the neighboring cell, I jam the plastic bag through the little bars. Behind the door, I hear people scramble.

I know the cakes came from someone in that cell—I am guessing the guy I often hear whispering to another person across the hall in Arabic, a language rarely heard in this prison and one that, unlike Farsi, I understand. Judging by their accents, I assume that our neighbor is a Saudi and the man across the hall is from Iraq or Kuwait. I’ve gathered that the man across the hall has a television, which is why he is always the bearer of tidings. Our neighbor has been asking for updates on the “Brotherhood,” which seems to roughly mean Al Qaeda, some other militant Sunni group, or all of them generally.

Sometimes, they’ve talked about us.

“Hey, the other day when I went to the bathroom I looked in the cell of those Americans. It’s like a five-star hotel in there. They have beds and a TV. And every day they go outside twice. Yeah, Iran is good to the Americans.” So badly I’ve wanted to interject, to tell them we didn’t, in fact, have a television and that we weren’t allowed to even make phone calls. But I’ve resisted.

I’ve refused to talk, despite our neighbor’s pounding on our wall and the coughs out into the hallway to get our attention.

I’ve refused because Sarah, Josh, and I made an agreement not to talk to anyone. The longer Sarah is alone, the more afraid—and paranoid—she has become that one of us will get caught doing something and that we will be separated again. For her sake, we don’t break the rules.

But now he is throwing cakes into our cell.

As the days pass, it becomes harder and harder to resist the urge to communicate. I am convinced it is safe—these two men talk to each other every day, loudly—and I am frustrated with Sarah’s lack of faith in my judgment. Eventually, Josh and I set a date: In two weeks, we will tell Sarah we want to actually talk to him.

Then one day, at hava khori, Sarah says, “Guys, I really want to talk to my neighbor. I will be really careful. Do you think it would be okay?”

“Sure,” I say. I am genuinely happy, because I want Sarah to connect with more people. She has been deteriorating. Her excitement at seeing us every day is desperate. She almost always leaves hava khori deflated and disappointed. People need people, and Sarah needs people more than most. It’s as if they found a special little torture just for her, and put it on a screen for us to watch every day.

“I’d really like to talk to our neighbor too,” I say. “He seems to know a lot about what’s going on.”

“Okay, just be careful,” she says.

Our neighbor says his name is Hamid, and when we start talking to him, our hall feels suddenly alive. He tells us that we are in Section 209, one of the political wards of Tehran’s giant Evin Prison. He teaches us the Farsi word for hostage, gurugan, which we use whenever we are frustrated with the guards, because they hate the idea.

He tries to reassure me: “America can do anything it wants to. You will be out soon. Trust me.” I disagree. “I think the US is just going to leave us here. We aren’t worth much to our government. If we really were spies, we’d be out by now. Iran is going to keep making demands for things like prisoner swaps, and the US will refuse. Iran won’t be able to back down. So how will we get out?”

The more I get to know Hamid, the more I see how similar his situation is to ours, except that no one, not even his family, knows what is happening to him. He says he was arrested for a visa technicality, that he has never been allowed to call anybody, and that he has never seen a lawyer or his embassy. He just went to court and they gave him a one-year sentence for visa forgery. “But don’t worry,” he tells me. “Illegal entry is only a six-month sentence.” We are coming up on five.

SARAH (Early January 2010)

I wake to insistent knocking on my wall. The new prisoner hasn’t stopped trying to get my attention since she came here after the protests. If I knock back, it will only lead to more communication, like whispering into the hallway or passing notes. There’s nothing I can do to help her, I tell myself sternly, trying to focus my attention back on my book.

“Sarah.” I suddenly hear a soft whisper. The voice is close, almost as if it were in my room. “Sarah.” My head darts to the right and left, looking for the source of the sound. Am I imagining it? “Sarah.” The voice is louder now. “Please.” It seems to be coming from the corner near the door, where my sink is. Above the sink is a vent. I leap off my bare mattress and climb onto the sink. I press my mouth to the vent.

“Who are you?” I ask the voice. “How do you know my name?” “My name is Zahra, almost the same as yours, Sarah. I know you.” “You know me?” “Yes, I saw your mother on TV. I am so sorry for you, Sarah. I am a mother too.” “Did you talk to my mother?” I almost yell, then remember to hush my voice. “Did you talk to her?” As soon as the question escapes my mouth, I realize how irrational it is.

“No, Sarah. But I saw many pictures of you on BBC. You are a small, beautiful girl. I know it must be easy for you to be standing on the sink. For me, it is difficult. They beat me. They kicked me and tortured me. My hips hurt and it is difficult for me to stand.” Her English is almost perfect, strongly accented with a sensuous, scratchy quality.

I feel tears welling up in my eyes. It’s a miracle, I think. She knows me! We can talk to each other! “Is—” I hesitate, but I have to ask. “Is my mother okay?” “I don’t know, dear Sarah. I am Dutch,” she says, “and Iranian. I live in the Netherlands, but my daughter is here, in Iran. They will not let me talk to my embassy. I don’t know if my embassy understands that I am here. When you see your embassy, please tell them about me, Zahra Bahrami.”

“They never let me see anyone,” I tell her. “I don’t know what’s happening. I’ve had no court, no trial. They won’t let me see my lawyer.” “Yes, I know. They are liars, Sarah. Don’t believe anything they say to you. I am your friend now, I love you.” I try to imagine her, hurt and alone, being taken out every day for beatings and interrogation and then put back in a cage. “Why did they arrest you?” I ask.

“I was at the protest,” she says, “Ashura.”

Suddenly, the door bursts open. Leila’s small, voluptuous silhouette is outlined in the doorway.

Not Leila, I think, of all people. I’ve managed to stay on her good side, and she’s helped me a lot—even complaining to the warden about how long they’ve kept me in solitary. I can’t afford to lose her.

But now her kind, motherly face slams shut like a steel door. She says she will tell my interrogators what I’ve done. Zahra is immediately transferred.

Now, when Leila comes to my cell, there are no more smiles, no conversations in Arabic. She hands me my food with a cold, unfocused stare, then wordlessly leads me out to the courtyard for a few minutes of sun. I’m no longer her ukhtee al-aziza, her sweet sister. I’m a plant that she gets paid to keep alive.

JOSH (Early January 2010)

At hava khori I have to hide from Sarah the depth of my relationship with Shane. Sarah has said that she felt left out around Shane and me on the hike, and now the prison has institutionalized that arrangement.

Shane and I try to avoid talking about funny moments in our cell or even the fact that the interrogators let us have a plastic chair. Sarah asked us not to say “we,” but we don’t always succeed, and she invariably shudders when we slip. I try to remind her that one day it will all be set straight: “When we’re released, you and Shane will be together all the time. I’ll be on my own.”

Sarah and I work to build our friendship so our triad’s dynamic doesn’t all hinge on Shane. She tells me about her days as a punk and about her relationship with her mother. She suggests friends of hers I should date in San Francisco. I tell her about Jenny, the friend I’ve wanted to marry since we dated in middle school, how I received long letters from her in September, and how I finally feel ready for her.

We schedule two weekly hava khori sessions in which Sarah and Shane can be alone. On Saturday mornings and Wednesday nights, I go to “small hava khori,” a room smaller than my cell but with a glass roof that allows me to see the sky.

SHANE (January 10, 2010)

The censors neglected to remove a staple from our letters. I pull it out with my long fingernails and bend the end to make a little hook.

I stick the hook delicately under the hem of my pink towel and pull the thread out, one stitch at a time. I do the same with my underwear, pulling out two long, white threads.

I tie the ends of these little threads to the zipper handle on my mattress. Like my sisters and I did as kids, I take three threads and weave them together, tying little knots over and over again. The knots form into a tiny little ring.

When we were all in solitary, I read books like Pride and Prejudice and Tess of the D’Urbervilles and paced my cell. I would only read a few pages at a time before I would put the book down, pace, and think. What have I been doing all these years? I’d ask myself. Why haven’t I proposed to Sarah yet? Are we going to just roll along together year by year, without ever deciding that it will be forever? I turned over these questions for months. I’ve never really believed in marriage, so part of me wondered whether I was being seduced into it by my isolation and those 19th-century novels.

But I love her so much. I do want to be with her forever. Though I see her every day now, she is still ripped away over and over again. I want to be Sarah’s sanctuary and I want her to be mine.

I tie off the thread spirals and leave enough loose string at the ends to make sure I can tie them onto our fingers. It’s date night, which means that Josh is going to stay in the cell while Sarah and I go out alone. I have the two little rings in my hand, white with a strip of red in the middle, like a stone.

Josh has no idea what I’m about to do. I don’t tell him because I’m afraid I might chicken out. I’m so nervous. What if she says no?

I get to hava khori before Sarah. It is dark and the late-winter air is a little cold. I lay a blanket down for us to sit on, under the camera so the guards won’t be able to watch.

When she comes out, I ask her if she wants to walk. We do a few rounds, my heart pounding as I try to make small talk. Then I stop and sit us down on the blanket.

I take her hands in mine. The single light, high up on the opposite wall, drowns out any view of the stars, but it casts a soft yellow glow on her face. Her hair is long now, drawn back in a ponytail, but I can’t see much of it under her purple hijab. Her lips are slightly redder than usual, probably from the strawberry jelly she uses sometimes for lipstick. She is beautiful.

I can see in her eyes that she doesn’t know what I’m going to say. I’m shivering even though it isn’t cold.

“Baby, I didn’t want to do this here. I wanted it to be somewhere beautiful, but—” She looks confused and a little worried. “Will you marry me?” Her body jolts with surprise. She squeezes my fingers. For a few moments, she says nothing. I hold my breath. Then she says yes.

I tie the rings onto each of our fingers and we hold each other, looking into each other’s eyes, smiling.

SARAH (February 2010)

About a week ago, the guard opened my door to hand me my lunch. Suddenly, another guard called her from down the hall and she left in a hurry. Standing with my food in my hand, I noticed a narrow, open crack in the door’s seam, which usually let in no light. She’d left it open. What difference does it make, I thought to myself—frozen with my eyes fixed on the crack—if my stupid door is open? In the hallway outside my cell, there is a video camera mounted on the wall. This hallway leads to another hallway with another camera. With no help from the outside, there’s no possibility of escape.

For months I had dreams of that damn door being left open—of magically walking out to freedom. Now that it actually was, all I wanted to do was close it. So I did.

JOSH (March 2010)

What I look forward to most is hava khori. It’s the time of day when I stop reading, writing, exercising, and just connect with my two friends. Increasingly, though, it doesn’t work out like that.

The arguments can be about anything. Shane wants to share meals at hava khori; Sarah doesn’t want food to distract us during these precious times together. Sarah and I want us three to read the same books at the same time; Shane doesn’t. Sarah wants us to appeal for clemency and apologize, but Shane and I don’t want anything that hints at admitting guilt.

I wrack my brain for an escape from our routine. I propose that we celebrate as many holidays as we can think of—as creatively as we possibly can, disregarding the actual calendar if we feel like it.

The night before Palm Sunday, each of us creates a personal system for palm reading. A few days later we decide it’s Ash Wednesday. We smear our faces with the chalky prayer stone, laughing at how ridiculous we look.

On Friday, I arrange a makeshift Seder plate: a hard-boiled egg, salt water, a fish bone as a lamb shank, lettuce as a bitter herb, and dried, flat Persian bread for matzo. Halfway through the Passover story, Sarah gets the giggles and can’t stop. She curls into Shane’s arms, laughing and embarrassed by her girlishness.

Shane looks at me, clearly uncomfortable. I call off the meal, a little ticked. I put effort into making the Seder special, and I refreshed my memory by reading the story of Moses in the Koran. Passover is my favorite Jewish holiday.

I peer down at my pathetic Seder plate, then over at Shane and Sarah balled together, and then I look over the walls to the cloudy spring sky. I quickly let it go. It was a nice week, but these distractions couldn’t last forever. Our holiday season is over.

SARAH (April 2010)

I’m in the middle of my exercise routine, doing jumping jacks and pushups, when I see a flurry of motion outside the slot on my door. I look down to find a tight ball of tissue paper on my floor. If the guards catch whoever threw this, my door will burst open any second. I will eat the note before they can take it.

Carefully smoothing out the crumpled note, I read: “Dearest Sarah, I am Zahra. Do you remember me? I have been very worried about you, my dear Sarah. They took me to a different section for talking with you, but now they have brought me back. Are you okay? Do you need help? I will talk to you tonight when the guards are sleeping.”

I can’t believe it’s her! It was almost four months ago that they moved Zahra. I’d often wondered what happened to her, but I never expected to see her again.

Later that night, there are loud knocks on my wall. I hear my name being whispered into the hallway. I crawl toward my cell door.

“Hello,” I whisper timidly through the slot.

“Sarah,” the voice replies, “I am Zahra. Do you remember me? I’ve missed you. Are you okay? Are you still alone? I’ve been very worried about you.” That night we devise a method of communicating through notes written on scraps of cardboard. She will write with a pen she stole from her interrogators and I will use a small piece of metal I’ve fashioned from a tube of Vaseline that leaves a mark like a pencil.

Zahra and I decide to hide our notes in the trash can in the bathroom. She balls hers up in toilet paper and I stuff mine inside soiled-looking maxi-pads—places the guards will never look. When one of us has a new note waiting, we will let the other one know by three hard knocks on our common wall.

I sometimes wait for days or weeks for the right opportunity to pass a note or exchange a few words with Zahra. I wait till the right guard is working—the one who never bothers to check on me through my peephole—so I won’t get caught writing. I memorize the guards’ footsteps and the patterns they walk in through the halls. I save a portion of beef stew in which I carefully soak a maxi-pad overnight, then let it dry for a day or two until it authentically looks like menstrual blood. If anything feels off, even the smallest detail, I abort the project.

Zahra is bold with the guards, sometimes making jokes, sometimes yelling at them. “I will not cry for these bastards,” she writes me. “I will not show them my tears.”

“We have to stop,” I write to her one morning. “I’m afraid we’ll get caught and they’ll move you. Zahra, when we are both free, I’ll come to see you in the Netherlands. We’ll spend days together dancing and talking. We will be friends forever.” A few days later Zahra passes by my cell and leaves another note balled up on my carpet.

“They are moving me again—don’t cry, Sarah! I don’t know what will happen to us, but remember you are never alone here. Sarah, please remember that Iranians are not bad people. We love the American people. I love you. No matter where they take me now, I will try to find you. Remember to listen for me—I will call out your name at night.”

Over the next several months I sometimes catch a glimpse of Zahra’s pink jumpsuit hanging on the prison clothesline. When the guards aren’t looking, I run my hands across the pretty color and sneak a few nuts or a piece of candy into her back pocket.

SHANE (May 20, 2010)

The guard we’ve nicknamed Dumb Guy is at our door. He hands us a bag of brand new jeans, shirts, socks, and sneakers with shoelaces. “Put these on, quickly,” he says, and leaves. We’ve been planning for this moment. Our moms have told us in letters they were trying to come and visit us.

After Dumb Guy is gone, I go to the bathroom. A tiny note, covered in microscopic writing, is wrapped tightly in plastic and stuck inside the outer lip of the sink. It’s small enough to fit discreetly between my middle and ring finger.

Josh and I have practiced this many times. I tape the note to my penis.

They took Sarah’s pen first, so we knew to hide one of ours before they raided our cell. I scribed this letter with our secret pen over several days while Josh stood watch for guards. It describes in detail what happened when we were captured and lays out a schedule of all of the events of our detainment, including prison transfers, hunger strikes, the arrival of books. It describes our daily routine and lists our email passwords in the hope that someone will change them. It has a list of songs we sing that we want our friends and family to listen to.

We are transported in a van with fogged windows to a hotel in another part of the city. Large, unsmiling men with radios and bellhop uniforms take us to the 15th floor. I ask to use the restroom, where I untape the note and put it in the coin pocket of my jeans.

They line us up in front of a set of double doors, where we stand on a red carpet, the kind movie stars walk down. Lights and cameras are blazing. The next thing I know, my mom is in my arms. I feel a warmth so pure that it awakens an old, lost part of me. I become loose in a way I haven’t been since we were hiking up that mountain 10 months ago. I pull the note out of my pocket and squeeze it into my mom’s hand. As I hug her, I tell her to hide it. She tucks it into her bra. Then, she whispers into my ear, “I love you, Shane. I can’t wait to have you home.” In this moment, I feel halfway there.

The men in suits sit us all down on a couch in front of a wall of cameras. Livia Leu Agosti, the Swiss ambassador, sits with us. I don’t understand how this is happening. After all those months of not letting us have pens in order to prevent any chance of communication to the outside world, why are they putting us in front of cameras, giving us a chance to say anything we want?

“What happened at the border?” a reporter asks.

“We never walked into Iran,” I say, then stop myself. I know our interrogators wouldn’t want us to answer that question. I feel an overwhelming need to self-censor. “We can’t really talk about that,” I say.

Suddenly, I realize why they brought us here—they aren’t afraid of us saying anything they don’t want us to. They control us. If I say anything even slightly offensive, any plans they might have to release us could be canceled. They exercise the same power over our mothers.

Something is different about my mom. She has always been a tough, no-nonsense kind of woman. Now she won’t let go of me.

“I hope they let you come home with us,” she says. Her words make my heart drop into my stomach. “I don’t think that’s going to happen, Mom,” I say gently, squeezing her hand. The three of us believe we’ll get out eventually, but we know the Iranians arranged this visit in order to hold us longer. By allowing us to see each other, they can claim they are making “humanitarian gestures,” subdue international pressure, and put the focus back on the United States to reciprocate.

The suits tell our moms they can remove their hijabs. They leave the room. At last, we are alone.

Leu Agosti jumps up and walks around the room, lifting up garbage cans and carpets to check for recording bugs. “This hotel is very famous,” she whispers. “This is where they bring prisoners to do videotaped confessions.” We ask her about the on-again, off-again talks over Iran’s nuclear program. She says she doesn’t believe that our detainment is directly tied to the nuclear issue, but “it doesn’t help.”

Mom talks about my friends as if they were hers. She and Sarah’s mom have been living together, working on our campaign full time. Our friend Shon Meckfessel, who was with us in Kurdistan, is moving in with them. Dad is raising money through hog roasts in rural Minnesota and by raffling off Bobcat skid loaders.

Sarah and I signal each other with our eyes and come together. We kneel on the floor in front of our moms and hold their hands. “Shane and I are getting married,” Sarah says.

“Congratulations,” they both say, somewhat nervously. I try to read their thoughts. Are they worried that we’re being rash, planning out our futures in such an extreme situation? Are they, both divorced, trying to hold back their own fears of marriage? Sarah shows them her ring of thread, and they soften, cooing about how romantic we are. Sarah’s mom asks, “Can we tell the media?”

SARAH

I can’t get over how strong my mom looks. All these months I’ve been imagining her defeated and broken, but I was wrong. I don’t have to protect her from what’s happening to me. Even if I want to, I can’t.

I ask her to follow me into the bathroom. We walk past the secret police hand in hand and lock the door behind us. “Mom,” I whisper, “about four months ago I found a lump in my left breast. It’s big and sore, and wasn’t there before. They took me to the prison doctor but didn’t allow me to ask her any questions. A few weeks later, they took me to a real hospital for a mammogram, but I haven’t seen the results. They say I’m fine, but I’m not sure I believe them.” I lift up my shirt and guide my mom’s hand to the spot that’s been tormenting me. Her skilled fingers gently prod the area—after a few seconds she looks up at me and shakes her head.

“It’s not cancer, sweetie. It’s just a totally normal lump. You don’t need to worry anymore.” My mom has been a nurse for more than 30 years—I know she wouldn’t lie to me about this. We hear a knock at the door and Dumb Guy tells us to come out.

“You’re fine,” my mom says. “Know that—but don’t stop demanding medical care. This is really important, okay?”

SHANE

The suits bring us menus and encourage us to order. I ask for shrimp and a chicken sandwich and fries and Coke and coffee. I eat it all, as well as some of the fruit heaped up on the table in front of us. Sarah sings songs she has written in prison. It is starting to feel surreal, like someone telling us to have fun at gunpoint.

Two hours after we eat, the Iranians tell us it’s time to go. We hug and kiss our moms and say every last thought we can think of as they usher us slowly down the hall. We wait in front of an elevator. When it opens, a man invites our moms to enter. They do, and we stare at each other, them on one side of the threshold and us on the other. Just as my heart starts to break, something inside me turns off.

Four months later, following international publicity about her health problems, Sarah is released on medical grounds. Over the next year, she meets with everyone from President Obama and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to Oprah Winfrey and Sean Penn, working nonstop with our friends and families on a campaign to get us released.

Josh and I are tried by the Revolutionary Court, on charges of masterminding an American-Israeli conspiracy against Iran, and sentenced to eight years. Eventually, the sultan of Oman pays a million-dollar “bail” and the two of us come home. (The sultan goes on to use the back channel opened up during the negotiations for our release to rekindle US-Iran nuclear talks.) Josh connects with his middle-school sweetheart, Jenny, and two years later their son, Isaiah, is born.

We also hear news about Sarah’s cell neighbor, Zahra with the pink jumpsuit. One morning, nine months after Sarah last saw her, she is taken out of her cell to Evin Prison’s death chamber. She is executed by hanging.