A mile north of the chaotic heart of downtown Rangoon, where electrical wires dangle haphazardly overhead and street vendors hawk roasted pig intestines, sits an upscale complex of 240 luxury residences overlooking the iconic Shwedagon Pagoda and a serene man-made lake. Marketed to wealthy expatriates and foreign businesspeople on extended stays in Burma’s bustling commercial capital, the newly built Shangri-La Serviced Apartments advertise “idyllic luxury in a modern metropolis” and amenities including a swimming pool, 24-hour private security, maids quarters, and a limousine service. Signs in the lobby inform guests that the complex now offers the Cartoon Network and yoga classes.

In 2011, Burma haltingly emerged from decades of oppressive rule by a military junta when a nominally civilian government came to power. The United States eased sanctions against the country the following year, and foreign investors rushed into this resource-rich frontier market. The influx of wealthy expats formed a ready-made clientele for the Shangri-La, where apartments rent for as much as $7,000 a month. In a country where about half the population lacks electricity and there are just six physicians for every 10,000 people, Shangri-La residents enjoy luxuries that are unfathomable to the surrounding populace, including an on-call private doctor and high-speed wifi.

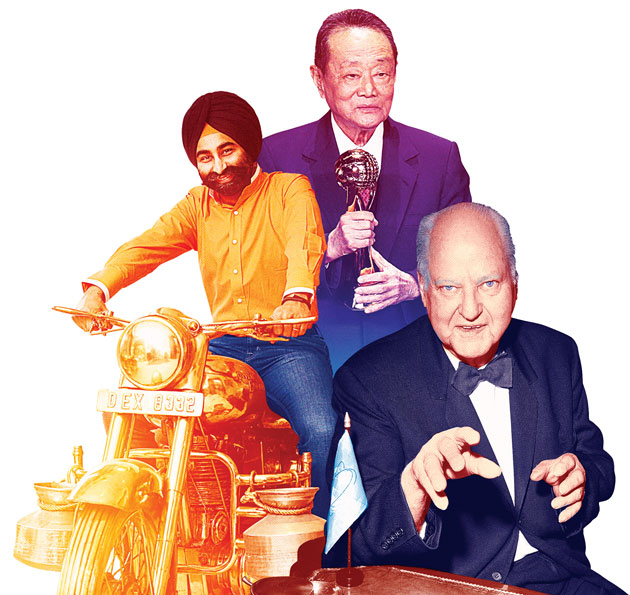

The apartments are part of a global business empire controlled by Malaysian billionaire Robert Kuok, one of Southeast Asia’s richest men and founder of the Shangri-La chain of hotels and resorts. His family’s diversified holdings extend from sugarcane plantations and real estate to one of the world’s largest palm oil companies, Wilmar International. “If you have a profit you have to take it,” the 92-year-old magnate recently told the Financial Times. “If you wait it will be your downfall.”

Kuok first gained a foothold in Burma in the 1990s when he partnered with Steven Law, who owns the country’s largest conglomerate and is the son of the late Lo Hsing Han, a notorious drug lord nicknamed the “godfather of heroin.” A leaked State Department cable dubbed Law “the regime’s top crony,” and in 2010 the Treasury Department imposed sanctions against both father and son. Together with Law, Kuok built what is now the Sule Shangri-La hotel in Rangoon, a popular destination for the Burmese and foreign elite.

In recent years, Kuok has teamed up with a far more respectable business partner to expand his chain of luxury hotels and resorts throughout Asia: the International Finance Corporation. A branch of the World Bank, the IFC finances the private sector in developing countries, via loans and direct investments, to help meet the bank’s goals of ending extreme poverty and “boosting shared prosperity.” In 2009, the IFC invested $50 million in the construction of a 142-villa Shangri-La resort in the Maldives. In 2012, it sank another $50 million into Kuok’s new five-star hotel in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. And in 2014, the IFC signed off on an $80 million investment in Kuok’s Burma properties that backed the construction of the luxury apartment complex and a makeover at the Rangoon hotel he built with Law. It was the IFC’s largest investment in Burma to date.

A Cold War-era institution, the IFC was envisioned by its founders as a soft-power antidote to the spread of communism. For years, it operated as a small, little-noticed arm of the World Bank. But over the last decade, its size, reach, and influence has exploded. A World Bank program called “structural adjustment” paved the way for its growth. This ’80s- and ’90s-era initiative conditioned loans to cash-strapped nations on whether they would agree to deregulate and privatize sectors of their economies, opening a new universe of opportunities to the IFC and investors of all stripes. Between 2000 and 2013, its share of the World Bank’s total spending jumped from 13 to 35 percent. In 2014, it approved more than $22 billion in financing. Over the years, even some World Bank insiders acknowledge, the IFC’s priorities have shifted, with anti-poverty efforts taking a backseat. “Poverty alleviation, does IFC see that as its primary role?” asks a former senior World Bank staffer. “I think you could question that.” He noted, “They’re pretending to be an investment bank.”

If so, the IFC is doing a pretty good imitation. In 2014, the organization earned $1.5 billion in profits.

The IFC is a moneymaker for the rest of the World Bank, handing over hundreds of millions of dollars annually to the bank’s International Development Association fund for the “poorest” countries. But in its pursuit of profits, the IFC has at times partnered with controversial oligarchs and made investments that, while contributing to its balance sheet, are of questionable benefit to the people it is supposed to be lifting out of poverty. And, says the former World Bank staffer, “there are examples of IFC making people worse off.”

We spent nine months investigating the IFC, visiting six countries (including Burma, India, and Romania) to get a ground-level view of its investments. We found that across Africa, Asia, eastern Europe, and Latin America, the IFC has backed enterprises that include private health care companies that cater to the elite and multinational supermarket chains known for poor labor practices and displacing small, family-run businesses. The main beneficiaries of the IFC’s largesse have included dozens of multinational corporations and private enterprises that are owned or controlled by some of the world’s richest people: The IFC has invested more than a billion dollars in luxury hotels and upscale property developments in poor countries—such as Kuok’s Shangri-La properties.

After you step through a metal detector into the hotel, the lobby’s opulent decor creates a jarring contrast with the chaotic streets outside its front doors. In one of the hotel’s restaurants, a rich banquet of lobster and elaborate desserts is laid out. “For me, living here as an expat, it’s fantastic,” says a British woman in a slinky red dress, sipping a glass of wine in the upstairs bar where a small plate of lime and pepper calamari tempura costs $15. “I can come here and get a glass of beautiful wine and use the wifi. For the wider community? I’m not sure.”

In 1950, as Sen. Joseph McCarthy fanned the flames of the second Red Scare, World Bank senior executive (and former General Mills vice president) Robert Garner lobbied for the creation of an institution that would help private companies expand into impoverished nations. “It was my firm conviction,” he said, “that the most promising future for the less-developed countries was the establishing of good private industry.” The notion for such a body had powerful backers, including Nelson Rockefeller, who headed the Truman administration’s International Development Advisory Board, and who thought it could be an effective tool for countering the Soviet Union’s influence in the developing world.

In 1956, the IFC opened for business under Garner’s leadership. While the World Bank was set up to fund reconstruction and development by lending money to governments, this new entity would finance businesses directly. Initially, the organization had a dozen staff members and $100 million in start-up capital from 31 member governments. Its first deal, in June 1957, was a $2 million loan to an affiliate of the German conglomerate Siemens, to expand the company’s manufacturing business in Brazil. In the coming years, the IFC would sink billions of dollars into ventures worldwide and would pioneer “emerging markets” as both a term and an asset class, radically changing the financial world’s perception of investments in developing countries. And as the institution has grown, so has its role in guiding the economies of these nations.

The IFC “flew under the radar for a long time, even as its investments increased,” says Kristen Genovese, a senior researcher at the Amsterdam-based nonprofit Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations. “Nobody really saw, or expected, the kind of impacts that we’re seeing today.”

Over the years, the IFC’s ranks have swelled to 184 member nations, which have contributed nearly $2.5 billion in capital since its founding; the US controls 20 percent of the votes on the 25-member board that oversees the institution. The IFC has expanded its portfolio of services, once focused exclusively on providing and guaranteeing loans to private businesses, to include taking equity (or ownership) stakes in companies. It has a venture capital wing, as well as a branch that manages the money of institutional investors, including pension and state-owned investment funds. Not unlike investment banks such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, the IFC has an advisory branch that counsels governments seeking to lure foreign capital into their countries.

Many of the IFC’s top officials hail from Wall Street firms, including its CEO, Jin-Yong Cai, who is stepping down at the end of 2015. Cai took the reins of the organization in 2012 after more than a decade at Goldman Sachs, where he was the investment bank’s top executive in China. In the IFC’s 2014 annual report, Cai touted the institution’s “consistent investment results” and declared, “Our investments have demonstrated that commercial and developmental success are mutually reinforcing—even in the most challenging areas.”

The picture on the ground, however, is far more complicated.

In Rangoon, we visited the offices of the IFC’s top official in Burma, Vikram Kumar, a onetime investment banker for Bank of America and India’s Yes Bank. Seated behind his desk, he explained the IFC’s rationale for backing Kuok’s Shangri-La properties. “We see it as business—enabling infrastructure, hotels—and it also fits under our jobs article, because of the number of jobs the tourism sector creates,” he says. Such talk frustrates many in Rangoon’s aid community. “There is an increasing tide of skepticism and concern about these development projects and how they will benefit people,” says one British employee of a large international development NGO.

The former senior World Bank staffer agrees: “I’m not sure what the impact on poverty alleviation is of that investment. You could argue that there will be jobs for construction workers, jobs for people who work in the hotel, jobs in the suppliers to the hotel, but it’s a very indirect kind of approach to poverty alleviation.”

According to IFC documents, the institution’s $80 million investment in the Shangri-La’s expansion in Rangoon was expected to create 1,000 temporary construction jobs and 600 permanent positions. That sounds like a lot, but consider that it translates to roughly $50,000 of investment per job—more than the average Burmese worker makes in a lifetime. The IFC says its investments have trickle-down effects. “Our research has shown that every job directly provided by our clients indirectly supports as many as 20 additional jobs across supply and distribution chains,” the IFC noted in its 2014 annual report. But the organization, as is often the case with its job-creation figures, provides little information to back up its claims. The IFC does not disclose its contracts and, though it is owned by the public, guards the details of its deals as zealously as any privately held corporation—as we discovered when we requested some information about the impact of its investments in a German conglomerate called the Schwarz Group, which it has financed to the tune of $350 million over the past decade.

Owned by a reclusive German billionaire, the Schwarz Group’s holdings include Lidl, a retail chain known as “Europe’s Walmart” that has come under criticism for union-busting and harsh labor practices. In one case, revealed by a German newsmagazine, internal documents showed that the company was surveilling employees while they used the bathroom to monitor how many toilet breaks they took. The IFC justified the Schwarz Group investments by saying they would create jobs and help local farmers in central and eastern Europe. But, when pressed on how much of Lidl’s products were purchased from local producers and how many jobs had been created by the company’s IFC-bankrolled expansion, a spokeswoman for the IFC, Elizabeth Price, refused to provide any details.

“It is typical for financial institutions considering an investment in a company to sign confidentiality agreements to protect the sensitive information they review in the course of assessing the company and its ongoing performance,” she said. “We simply cannot disclose competitive information without consent of the company, and in this case, the information you request about the exact employment and local sourcing number is confidential.”

Some of the most pointed criticism of the IFC comes from within the World Bank itself. The bank’s internal watchdog, the Independent Evaluation Group, has repeatedly faulted the IFC for failing to live up to its anti-poverty mandate. “Most IFC investment projects generate satisfactory economic returns but do not provide evidence of identifiable opportunities for the poor,” the watchdog reported in 2011. If anything, the situation appears to have worsened since then. In April 2015, the IEG reported a “decline, particularly in upfront screening, appraisal, and structuring” of deals, and a “long-term, steady downward trend” of the development performance of the IFC’s investments.

The IFC says it makes investments after weighing developmental impacts and any potential for environmental damage and human rights abuses. The organization also says it evaluates deals to avoid partnering with unsavory characters and companies that could damage the IFC’s reputation or balance sheet. But, in a number of cases, the IFC has been accused of disregarding its own guidelines.

Take its $30 million investment, announced in 2009, in Corporación Dinant, an agribusiness conglomerate controlled by the infamous oligarch Miguel Facussé Barjum (who died last June). For years, human rights organizations have accused Facussé’s company of taking part in landgrabs and violence against Honduran peasants in the Bajo Aguán, where Dinant has been expanding its empire. As the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the Huffington Post noted in their award-winning series on the World Bank, “the IFC aligned itself with one of the key players in a deadly civil conflict, staking its money and reputation on a powerful corporation with a questionable history.”

When the World Bank’s Compliance Advisor/Ombudsman—a separate watchdog within the bank—investigated the Dinant deal, it discovered that staff members who focused on social and environmental standards had been cowed by the investment side of the organization. Raising red flags about these issues, the report noted, was seen as affecting “decisions about promotions and pay increases.”

Luiz Vieira, coordinator of the UK-based Bretton Woods Project, an NGO that monitors the World Bank, says the IFC’s “drive for profit…skews the decision-making process around the selection of projects.” And he observes that it is likely difficult for the IFC’s investment staff “to take a developmental perspective on what they’re doing. That’s not the type of people they attract and they don’t focus on that.” A recent World Bank staff survey found that only 30 percent of IFC employees considered development as their main objective.

“There has always been a tension between IFC as a development institution or IFC as a financial institution, and depending on the leadership it tends toward one way or the other,” says a former senior IFC official. “It is leaning more toward the financial institution model now.”

At the heart of concerns about the IFC’s investment policies is a deep potential conflict built into the IFC’s mission: It invests directly in companies, but it also advises nations on how to attract investors, often via privatization and deregulation—policies that can directly benefit the companies it takes stakes in. As a group of six NGOs, including ActionAid and Christian Aid, noted in a 2010 report, “It is highly problematic for a multilateral institution to position itself as an objective source of policy advice on matters where it has a direct financial stake in the outcome, particularly in low-income countries that may not have the resources to procure advice from other sources, or in countries where weak democratic processes do not provide adequate checks and balances relative to external donors.”

In its 2014 annual report, the IFC acknowledged that “actual or perceived conflicts of interest can arise” from wearing multiple hats, but it claimed it had “implemented processes to manage these conflicts.”

But serving as both adviser and investor can create perverse incentives. Take the IFC’s role in the privatization of water services in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. In the 1990s, the organization advised the Philippine government on privatization efforts. It also conducted the bidding for contracts to take over these services. Then it took an equity stake in a joint venture called Manila Water, which won the contract to supply water to the eastern half of the city. In total, the IFC loaned the joint venture $160 million and acquired a $15 million equity share in the project.

“Fifteen years later, residents of Manila have suffered under declining water quality and access,” Corporate Accountability International, a Boston-based watchdog group, reported in 2012. “Hundreds of communities remain without safe water, and the cost of a connection, even where available, is unaffordable for many of the city’s residents.” This case, it said, demonstrates how “profitability, not human access to water, is the primary incentive when the World Bank becomes a corporate shareholder.”

Frederick Jones, an IFC spokesman, contested this claim. He said in an email that access to water had increased from “just 58% of the population…in the 1990s to 99% today,” and that “water quality improved greatly.” The “IFC has different departments handling advisory and investment services and we maintain strict divisions between them,” he added. “When governments seek our services as advisors, we help them run a competitive and transparent process to find the best partner.”

But NGOs are not the only ones concerned about possible conflicts of interest. In 2011, former World Bank economist Guillermo Perry argued that “there is no doubt that dealing with both governments and private firms may create incentives or even [the] occasion for advising on a policy or regulation that is self-serving to [the] equity or debt interests in particular firms or sectors.”

The IFC’s efforts in the health care sector have been particularly controversial. While pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into private hospitals and clinics, the organization has simultaneously advised governments to privatize aspects of their health care systems or to forge private-public partnerships. Oxfam, the international aid group, revealed last year that one IFC-facilitated partnership in Lesotho—a project the IFC claimed would “transform health care” in the country—was in fact consuming 51 percent of the nation’s health care budget, while the private company involved in the deal was reaping 25 percent returns. (After the group published its findings, the IFC challenged its figures. The project, the IFC said, actually ate up just 35 percent of the country’s health budget.)

In 2009, the IFC launched a separate $1 billion effort to support the expansion of for-profit health care in Africa. The stated aim of the initiative, dubbed Health in Africa, was to “catalyze sustained improvements in access to quality health,” with an “emphasis on the underserved.” But it, too, has been criticized for doing little to improve the lives of the poor. Some of the IFC’s Health in Africa funding, for instance, went to a Nigerian fertility clinic where a single round of in vitro fertilization costs more than $4,600. This is more than a minimum-wage Nigerian worker could hope to earn in four years.

Jones, the IFC spokesman, declined to answer questions about the clinic, but said in a statement, “The Health in Africa Fund invests in a broad range of health activities…to increase access to quality care for low- and middle-income populations.”

In another health-related initiative, the IFC, starting in 2002, has advised Romania to “reshape the country’s healthcare system in order to encourage greater private-sector participation.” Three years later, the IFC began advising a Romanian private health care company called MedLife on “the design and business strategy” for a new private hospital. The following year, the IFC made a $5 million equity investment in the company, which it described as “the first private hospital chain in Romania.”

Founded by the Marcu family, a clan of prominent doctors and bankers, MedLife today dominates Romania’s private health care market. It is also popular with international medical tourists who travel to the country for treatment at cheaper rates than they would find in other European nations. The company’s services include “the full range of surgical and non-surgical beauty procedures.”

MedLife’s president is Mihai Marcu, a stocky former investment banker with close-cropped hair. When we met him in his seventh-floor office overlooking central Bucharest, he told us that it was a “very special and unique thing…for the World Bank through their IFC division to become shareholders along with a family.” The IFC is not supposed to be competing with banks; its mandate is to invest only where private capital cannot otherwise be obtained. But Marcu boasted that he could have easily secured funding to expand MedLife from private equity firms or commercial banks. “Don’t forget, my background is in banking and risk, so always I have an open door to the bankers in Bucharest,” he said. However, he said MedLife has benefited from the “huge expertise” of the IFC, which took company representatives to visit hospitals in London and Washington, DC. The IFC’s backing also was a boon, he said, “with the [company’s] image,” helping it to attract clients and staff.

Marcu said more than 4 million Romanians have visited MedLife—or 1 in 5 of the country’s 20 million residents. He also admitted, though, that many patients do not have the money to complete their treatments: “Kidney [and] heart patients, many cannot afford MedLife.” He estimated that only 20 to 30 percent of these patients stay with the company for their treatment. Those who can’t afford MedLife’s fees, Marcu said, “are referred to the state hospitals.”

Romania, Marcu explained, is a “two-speed” society: The poor are poor because they “do not want so much to work.” Those are the people, he said, who can’t afford MedLife: “They don’t want to develop and do things.”

In 1974, when Robert McNamara headed the World Bank following his controversial stint as US defense secretary, he spoke at an internal seminar on the organization’s policies and practices. In his closing remarks, he warned that “the closer the IFC moves to being a commercial enterprise, the less capable it will be to perform development functions.” More than 40 years later, the tension between the IFC’s mandate to help end global poverty and turn a profit has grown only more pronounced.

In April, a group of farmers and fishermen from the state of Gujarat in western India filed a historic lawsuit against the IFC in a US federal court. They alleged the organization had wrecked their livelihoods by financing the construction of an “ultra mega” power plant that had polluted the land and water. The case marks the first time a community has challenged the IFC over one of its projects, and it spotlights the institution’s conflicting mission. Salim Umar Vager, a 47-year-old fisherman and father of six who works downstream from the plant, says his daily catch has declined from more than 100 pounds to about 20. “I believe after five years there will be no fishing left here,” he says, pointing out that 400 people work at the newly constructed plant, while nearly 2,000 families are directly affected by it. “For 400 people’s livelihoods, they have destroyed thousands of others.”

The IFC’s priorities are unlikely to change under the leadership of its new CEO, Philippe Le Houérou, a longtime World Bank official. If anything, the pressure on IFC investment officers to secure multimillion-dollar deals and turn profits, regardless of the costs, may only increase. The World Bank has pledged to do more in what it calls “fragile and conflict-affected states,” where risks are higher and prospects for returns, development or financial, are less assured. And, thanks to the economic rise of countries such as India and China, the IFC now has competitors: In 2014, the presidents of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa formally unveiled their version of the World Bank, which is called the New Development Bank—also known as the “BRICS Bank.” China has established an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, whose 50 members include more than a dozen nations from the Asia-Pacific region, as well as Egypt, Germany, and the United Kingdom. (The United States has so far declined to join.)

As the IFC contends with regional rivals, McNamara’s prescient admonition has all but faded from memory. “There’s a sense from the [IFC’s] board to ‘let the IFC alone,'” says the former IFC official, “and let the money just flow.”

This story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.