At elementary schools nationwide, a health curriculum called Energy Balance 101 has taught millions of kids a seemingly simple concept: In order to stay fit, all we need to do is balance the food we eat with exercise. In the first lesson, elementary schoolers learn that anything and everything takes energy, from playing sports to doing homework. Teachers are instructed to ask how much you would need to eat or drink in order to “balance shooting baskets for 30 minutes.” Calories in, calories out.

Sensible enough, right? But there’s something odd about the curriculum: Not once does it suggest ditching junk food—in fact, the lesson plan explicitly says, “There are no good foods or bad foods!”

This approach isn’t surprising when you consider the source. The class is part of Together Counts, an educational campaign promoting energy balance that is wholly funded by a group called the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation—which is in turn run and bankrolled by junk food corporations. Indra Nooyi, CEO of PepsiCo, is the chair of the board, and directors include the CEOs of Kellogg, Hershey, Nestle USA, Coca-Cola, Unilever, Smucker, and General Mills. The organization’s mission, according to tax filings, is “to help families and schools reduce obesity—especially childhood obesity.”

In addition to schools, the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, which has an annual budget of about $10 million, funds energy balance programs for a wide variety of organizations, including the Girl Scouts, the National Parent Teacher Association, and the National Head Start Association. A Boy Scouts program is in the works. Moms are sponsored to blog about the benefits of the energy balance programs. In all, HWCF estimates that 28 million students from pre-K through fifth grade have taken part in the program, as well as another 1.7 million Girl Scouts. (The Girl Scouts maintains that the curriculum was introduced as a “short term…optional activity” and is “not a part of any national programing.”)

Together Counts isn’t the only energy balance campaign supported by junk food companies. Earlier this year, Coca-Cola came under scrutiny after the New York Times revealed that the company had provided $1.5 million in seed funding to start the Global Energy Balance Network, a think tank that downplays the role of sodas in causing the obesity epidemic. Just yesterday, GEBN announced it was disbanding “due to resource limitations.” Last week, Coca-Cola science and health officer Rhona Applebaum, who helped establish GEBN, stepped down.

McDonald’s, meanwhile, has marketed energy balance for years; in 2005, with the rollout of a new jingle (“It’s what I eat and what I do…I’m lovin’ it”) former CEO Jim Skinner said, “One of the best things we can do is communicate the importance of energy balance in an engaging and simple way.” In the most recent corporate social-responsibility report of Yum! Brands, which is the parent of Taco Bell, Pizza Hut, and KFC, nutrition officer Jonathan Blum says, “We believe that all of our food can be part of a balanced lifestyle if eaten in moderation and balanced with exercise.”

Again and again, the HWCF lesson plans drive home a single message: All foods can be good sources of energy—as long as you exercise enough. In the first of four lessons in Energy Balance 101, elementary school students play a game matching up calories in foods with activities (e.g. “chocolate/nut candy bar” = playing soccer for an hour and a half), and learn that 21 carrots and a chocolate chip cookie have the same number of calories, though cookies have fewer nutrients. “Does this mean we should not eat the chocolate chip cookies?” reads the lesson plan. “No! Cookies taste good and they are fun to eat,” as long as they’re part of a “balanced diet.” Teachers and students are encouraged to visit the Together Counts website, which features games like the Scales of Energy, where one learns, for example, that going for a bike ride can balance out eating a chocolate bar.

In a Girl Scouts handbook, fourth and fifth grade students learn to space out calorie intake: “Instead of eating a small bag of potato chips, you could eat half and save the rest for another time.”

In a curriculum implemented in Head Start programs, preschoolers shop from an imaginary grocery store. Teachers are to “remind students that all foods can fit into one of five food groups”: fruits, vegetables, meat, grains, and dairy.

HWCF maintains that its funders have no say over the Together Counts curriculum. Rather, Discovery Education, a branch of Discovery Communications, designs the curriculum in line with the latest government-released data. “We basically underwrite Discovery’s ability to extend their curriculum in the health and wellness space,” says HWCF president Lisa Gable. Liz Hillman, the senior vice president of communications for Discovery, says the Together Counts curriculum is just “one of the many ways we approach free resources around health and wellness for students across Discovery Educations services.”

Regardless of who constructs the curriculum, scientists point out that there’s a major problem with programs like Energy Balance 101: Study after study shows that not all calories are created equal, because our bodies metabolize them differently. Robert Lustig, a pediatric neuroendocrinologist at the University of California-San Francisco, believes that programs that emphasize exercise over diet are on the wrong track. “A calorie is a calorie—it’s the first thing dieticians learn in dietary school,” he says. “That’s the mantra, and guess what? It doesn’t work.”

Take sugar. Virtually every cell in the body contains enzymes that can turn glucose—the sugar in starches like bread or potatoes—into energy. But only the liver has the proteins necessary to do the same for fructose—the stuff that makes table sugar and high-fructose corn syrup so sweet. When the liver is forced to metabolize lots of fructose at once, much of it is converted to fat, leaving us hungry. “It’s like what the IRS does to your paycheck: gone before you had the chance to burn it,” says Lustig. Plus, sugar doesn’t trigger the hormone that tells us we’re full, so we tend to overeat when we have sweet foods and drinks. Over time, Lustig says, that process of overwhelming the liver drives illnesses from diabetes to heart disease.

A 2013 study by Lustig and his colleagues examined data on food availability and diabetes prevalence across the world, and found that while eating an extra 150 calories per day wasn’t associated with an increase in diabetes, eating an extra 150 calories of sugar per day was correlated with an elevenfold increase in diabetes rates. A similar concept applies to fats. Unsaturated fats—the kind in olive oil, fish, and avocado—reduce the risk of heart disease, while saturated fats—like those in burgers and fries—do the opposite.

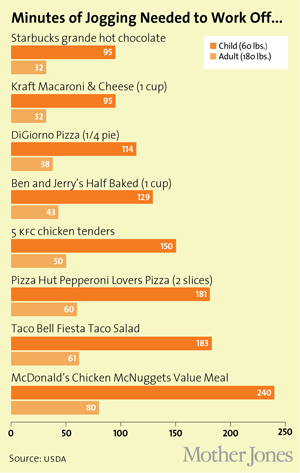

Regardless of the long term-effects of junk food, adds Barry Popkins, a food researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the majority of research confirms the importance of prioritizing diet over the exercise in promoting weight reduction in part because it takes a huge amount of time to work off the calories in junk food. “We’ll never be able to move enough to offset one or two Cokes a day,” he says. His research has found that roughly 60 percent of the American population consumes the equivalent of a Coke per day in sugary beverages—from sugar-heavy lattes to energy drinks. For a 60-pound kid, working off the calories in a Coke means jogging for more than an hour.

Of course, Lustig points out, these details are exactly what junk food companies gloss over in programs like Energy Balance 101. “By focusing on calories, they’re basically saying…it’s your fault,” he says. “It’s a great way to absolve themselves of culpability.”