They are all white, all middle-aged, and all men. A few live openly lavish lifestyles, but the majority fly under the radar. Rarely is there news about them in the mainstream media or even the trade press. Their obscurity would seem unremarkable if we were talking about the biggest manufacturers of auto accessories or heating systems. But these are America’s top gunmakers—leaders of the nation’s most controversial industry. They have kept their heads down and their fingerprints off regulations designed to protect their businesses—foremost a law that shields gun companies from liability for crimes committed with their products.

With this investigation, Mother Jones set out to break through the opacity surrounding the $8 billion firearms industry and the men who control it. While the three largest companies disclose some financials, the rest are privately held. Some are further shrouded by private-equity funds or shell corporations based in overseas tax havens. We mined manufacturing data and import statistics from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). We also examined obscure press clippings, court documents, private industry reports, and tax records from the Treasury Department. Together, the 10 companies we investigated produce more than 8 million firearms per year for buyers in the United States, accounting for more than two-thirds of the total market. (None of the companies responded to our requests for further information.)

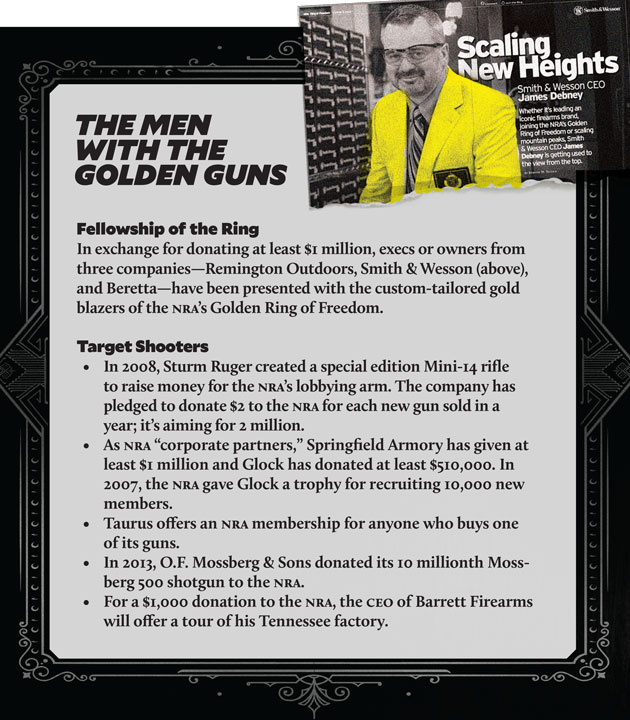

Many of these companies’ top executives have donned the jacket bestowed to members of the Golden Ring of Freedom, an exclusive club for $1 million-plus donors to the National Rifle Association. Several have been the focus of criminal investigations and lawsuits over everything from arms trafficking and fraud to armed robbery and racketeering.

As the debate over gun laws has grown louder, sales have soared. In the year following the massacre in Newtown, Connecticut, the three largest gunmakers—Sturm Ruger, Remington Outdoor, and Smith & Wesson—netted more than $390 million in profits on record sales. Shares in publicly traded Sturm Ruger and Smith & Wesson jumped more than 70 percent that year, benefiting institutional investors such as Vanguard, Blackrock, and Fidelity. The hedge fund that owns Remington Outdoor—maker of the assault rifle used in Newtown—saw the annual return on its investment grow tenfold.

And the picture looks no different today, on the heels of the deadliest mass shooting in modern US history. President Barack Obama once again mournfully addressed the nation after the massacre in Orlando—which was carried out with a Sig Sauer assault rifle designed for US special operations forces, the civilian sales of which have helped make Sig Sauer the fifth largest producer of firearms for the US market. In what has become a typical pattern after gun massacres, the stock prices of publicly traded Sturm Ruger and Smith & Wesson on Monday both jumped more than 6 percent (on a day when all the broader market averages dropped).

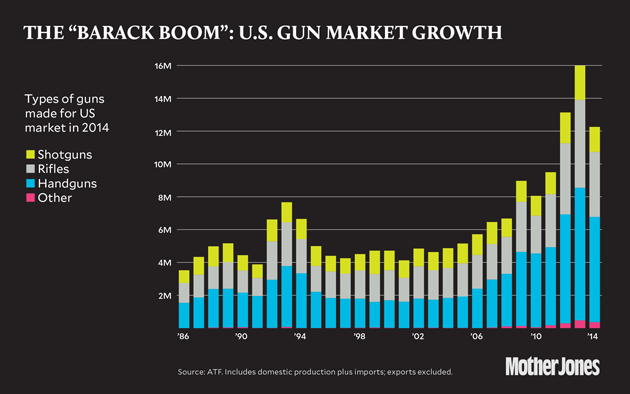

The upshot is that even as gun ownership has declined from approximately half to one-third of American households, those who do own guns are stockpiling them in record numbers. As the head of one investment firm put it, “Mr. Obama is the best gun salesman on the planet.”

1. Sturm Ruger

“No honest man needs more than 10 rounds in any gun,” a Sturm Ruger co-founder, the late William Ruger Sr., told Tom Brokaw in 1992. “I never meant for simple civilians to have my 20- or 30-round mags or my folding stock.” By 1994, with even Ronald Reagan voicing support, Congress banned high-capacity magazines as well as assault rifles. But a decade later, lawmakers let the ban expire amid pressure from the National Rifle Association. By then the elder Ruger was deceased, and the Connecticut-based company resumed civilian sales of 30-round magazines. Since 2007, the company has sold more guns in the United States than any other manufacturer.

As the business grew, Sturm Ruger CEO Michael Fifer lobbied personally against a Connecticut ban on high-capacity magazines, commonly used with the company’s semi-automatic rifles. “The regulation of magazine capacity will not deter crime, but will instead put law-abiding citizens at risk of harm,” Fifer wrote to state lawmakers in early 2011. The legislation died in committee that April. At the NRA’s annual Corporate Executives Luncheon the next year, Fifer presented a check to the group for more than $1.25 million—$1 for every Sturm Ruger gun purchased the prior year. Eight months later, 20-year-old Adam Lanza used a semi-automatic rifle and a 30-round magazine to gun down 20 children and six adults at Newtown’s Sandy Hook Elementary School, located just 27 miles from Sturm Ruger’s headquarters.

In the year following the shooting, Sturm Ruger’s profits increased 56 percent. Fifer’s compensation that year was more than $2.6 million. He sits on the board of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a lobby group based in Newtown and run by former Sturm Ruger executive Steve Sanetti. Sturm Ruger’s largest shareholders are mutual fund giant Vanguard Group and a private investment firm, London Company of Virginia, which has assets worth $10.6 billion, including holdings in ammunition, cigarettes, missiles, and caskets.

2. Remington Outdoor

Shortly after Newtown, Stephen Feinberg, CEO of the $29 billion private-equity fund Cerberus Capital Management, pledged to sell off Remington Outdoor, the maker of the Bushmaster XM-15 used in the massacre. The company soon indicated it couldn’t find a buyer, but notably Remington’s profits increased nearly thirtyfold over the next year, with the biggest jump in sales coming from assault rifles. The company attributed the spike to “consumer concern over more restrictive governmental regulation.” With stakeholders such as the California teachers’ pension fund threatening to divest, Cerberus distanced itself from the politics. “Our role is to make investments on behalf of our clients,” the company stated. “It is not our role to take positions or attempt to shape or influence the gun control policy debate.”

In May 2013, the NRA inducted three Remington executives—CEO George Kollitides, Vice Chairman Wally McLallen, and President Scott Blackwell—into its Golden Ring of Freedom, reserved for those who’ve given the NRA at least $1 million. Kollitides has also served on the nominating committee that controls who sits on the NRA board. “It’s very easy to blame an inanimate object,” Kollitides said of the Bushmaster rifle used in Newtown.

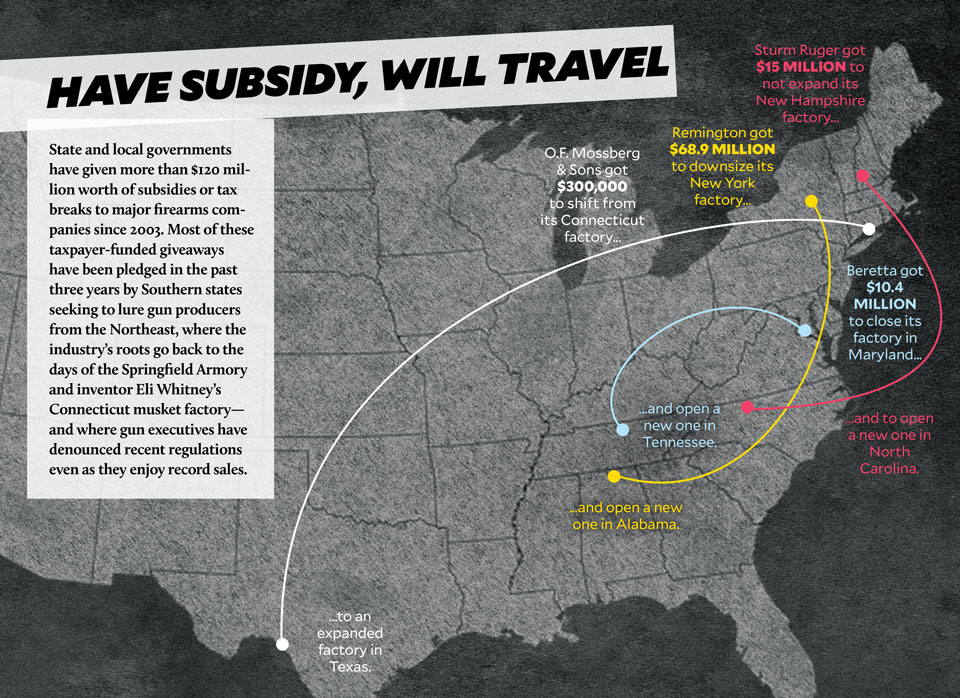

After New York state enacted stricter gun laws in 2013, Remington laid off workers at its 200-year-old factory there and moved production to Huntsville, Alabama, where it gets $69 million in state and local subsidies—or about $14 for every Alabama resident. On a tour of the new plant, Remington and NRA executives were joined by GOP Sen. Richard Shelby—a co-sponsor of the 2005 law shielding gun companies from liability—who was running for reelection. The NRA executive endorsed Shelby’s campaign as Remington’s current CEO, Jim “Marco” Marcotuli (formerly a Cerberus executive), stood smiling at Shelby’s side.

3. Smith & Wesson

In August 2013, upward of 150 Smith & Wesson employees descended on a hearing with Massachusetts legislators to denounce proposed gun restrictions. The following year, CEO James Debney, already a member of the NRA’s Golden Ring of Freedom, presented NRA Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre with a check for an additional $600,000. “Through its various programs, pro-gun-reform legislation, and grassroots efforts,” Debney said, “the existence of the NRA is crucial to the preservation of the shooting sports and to the entire firearms industry.”

America’s third-largest gunmaker has come a long way from a deal it cut in 2000 with the Clinton administration. Back then, Smith & Wesson received immunity from product liability lawsuits in exchange for agreeing to install safety devices, not to sell to unscrupulous dealers, and to limit bulk handgun sales. It also pledged to make “smart gun” technology available within three years.

The deal enraged industry bigwigs. “Boycott Smith now and forever. Run them out of the country,” an executive at rival Kimber America wrote to fellow firearms leaders. “You guys need to make sure that no one else is going to join the surrender.” After a boycott led by the NRA sent sales plummeting more than 40 percent, Smith & Wesson’s British parent company sold it at a $100 million loss to Saf-T-Hammer Corp., a startup run by Robert L. Scott, a former Smith & Wesson VP. Scott reneged on the Clinton deal. “It was important that we be an active part of the industry again,” he said in a 2002 deposition. (Today, Scott chairs the board of the National Shooting Sports Foundation.)

The company soon drew attention in other ways. In 2004, the Arizona Republic reported that 74-year-old Chairman James Joseph Minder had once been a serial armed robber known as the “shotgun bandit” who’d committed eight holdups in Michigan. (Minder soon resigned.) In 2010, a VP of sales was indicted for attempting to bribe an FBI officer posing as an African emissary taking bids on a $15 million arms deal. And in 2014, Smith & Wesson agreed to pay $2 million to settle charges that it had bribed foreign officials in Pakistan and Indonesia.

4. Glock

Gaston Glock, an Austrian curtain rod manufacturer, designed the Glock 17 in his garage outside Vienna in the early 1980s. Soon it was a global bestseller. Alarmed by aspects of the pistol’s revolutionary polymer design—including the lack of a conventional safety mechanism—Congress held hearings on the Glock in 1986 and New York City banned it. Yet the Glock remains by far America’s most popular pistol—carried by two-thirds of police officers, immortalized by hip-hop and Hollywood, and wielded by the perpetrators of the Virginia Tech, Tucson, Aurora, and Charleston massacres.

Gaston Glock resides in an opulent Austrian villa. He has two corporate jets worth eight figures and a $3 million helicopter to shuttle him around Europe. In the 1980s, some of Glock’s biggest law enforcement contracts were allegedly won with the help of Gold Club strippers near the company’s US headquarters in Smyrna, Georgia. “For a lot of guys coming in from out of town, this was the best time they were going to have all year, or maybe their entire life,” a former police official told journalist Paul Barrett for his book Glock: The Rise of America’s Gun. “You go to Smyrna, get laid at the best strip club in town, drink champagne—you are not going to forget the experience when it comes time to choose between Glock and Smith & Wesson.”

By the 1990s, Gaston Glock was a billionaire and had hired New Jersey attorney and gun rights activist Paul Jannuzzo to help combat a rash of claims by shooting victims. Jannuzzo, who eventually became the CEO of the US subsidiary, convinced Glock to donate $1 to the American Shooting Sports Council for each gun shipped from Smyrna. But ties between Jannuzzo and Gaston Glock began to fray over an amorous rivalry for the company’s young human resources manager. Jannuzzo was convicted in 2012 of diverting profits into his own bank account; an appeals court later found the statute of limitations had expired and overturned the verdict.

In 1999, at the age of 70, Glock survived a hit job in a Luxembourg parking garage carried out by a mallet-wielding former French legionnaire nicknamed Spartacus. Glock knocked out several of his attacker’s teeth before rendering him unconscious. The police linked the attack to an embezzlement scheme by Glock’s business associate Charles Ewert, who’d earned the nickname Panama Charlie for helping Glock set up foreign shell companies to evade Austrian and US taxes. Investigators hired by Glock later alleged that Ewert had misappropriated $103 million in corporate funds.

According to a lawsuit filed against Glock by one of those investigators, Glock knowingly participated in the scheme—allegedly paying himself royalties for nonexistent trademarks and laundering money with phony payments, rents, and loans. When the investigators confronted Glock, he convinced state and local officials in Georgia to indict them instead, on charges that they’d overbilled him for legal services. The charges, later dropped, “were fabricated based on falsified evidence, influenced witnesses, and evidence either destroyed or withheld,” according to the suit.

Glock also faces allegations stemming from his 2011 divorce, in which he left Helga, his wife of 49 years, for Kathrin Tschikof, a 31-year-old nurse who’d helped him recover from a stroke. Tschikof now directs the Glock Horse Performance Center, overseeing the couple’s 50 dressage horses and jumpers. In May 2014, Glock bought Tschikof a $15 million Olympic silver-medal-winning show horse, one of the most expensive ever. Six months later, Helga Glock filed a $500 million lawsuit accusing her ex-husband of bamboozling her and their three adult children out of a stake in the company and concealing hundreds of millions in profits. Gaston Glock called the suit a shakedown scheme. Helga’s attorney insists she, not Gaston, is the victim.

“He’s got a lot of skeletons,” former Glock executive Peter Manown said in court after pleading guilty to stealing from the company. “He’s done, in my mind, a lot of things that are much worse than what Jannuzzo and I did. He makes roughly $200,000 a day—he personally. He spends money on mistresses, on houses, on sex, on cars. He bribes people. He’s just a bad guy.”

5. Sig Sauer

“We have clearly defined our path to growth as being in emerging markets and developing countries,” Ron Cohen, the CEO of Sig Sauer’s US subsidiary, told Management Today in 2014. Later that year, German investigators searched the home of Sig Sauer co-owner Michael Lüke seeking evidence of illegal arms deals. Lüke allegedly sent German-made guns through Cohen’s office to bypass European restrictions on arms exports to conflict zones in Iraq, Colombia, and Kazakhstan, according to the German paper Suddeutsche Zeitung.

In March 2015, German officials discovered that key evidence in the case had been stolen from the prosecutor’s office before it could be introduced at trial. Citing the ongoing investigation, German officials have blocked Sig Sauer from exporting guns outside the European Union. Sig Sauer fans in the United States need not worry: 477,000 of the company’s guns are made each year in Newington, New Hampshire.

Sig Sauer dates to the mid-1800s, when it became a weapons supplier to the Swiss army. To get around Swiss arms export restrictions, in the 1970s the company merged with a German firm, opening an office in 1985 in Virginia. In 2000, the company spun off its arms division to Lüke and fellow German investor Thomas Ortmeier, who focused on the US market and now claim to supply nearly 1 in 3 guns used by American law enforcement officers. In 2014, Sig Sauer announced it would slash its German workforce by two-thirds and produce more guns in the United States.

Cohen commanded a combat unit in the Israeli military during the Lebanon War. “You lead by example,” he told Management Today. “You learn how to overcome anything, and there is a drive to constantly move forward. There is a sense of, ‘If we don’t move, we die.’ That’s a big part of who I am.” (Cohen did not respond to a request for comment about the use of a Sig Sauer rifle in the Orlando massacre.)

Last December, presidential candidate Ted Cruz joined Sig Sauer representatives for a shooting demonstration at an Iowa gun range. In February, Donald Trump’s sons Eric and Donald Jr. paid a visit to Sig Sauer’s New Hampshire factory, earning praise on the company’s Twitter account for “taking time to understand #whoweare #whatwedo #LiveFreeorDie.”

6. O.F. Mossberg & Sons

America’s oldest family-owned gun manufacturer is based in North Haven, Connecticut, 25 miles from Newtown. The day of the massacre, some employees worked the assembly line with tears in their eyes. Mossberg Senior Vice President Joseph Bartozzi criticized the NRA’s defiant response to the mass shooting as insensitive. “The funerals were still going,” he told Bloomberg. “Parents were burying their children.”

Two months later, however, the company pulled out of a major Pennsylvania gun exhibition because the sponsors, out of deference to Newtown’s families, had banned semi-automatic rifles and high-capacity magazines. “Mossberg’s position on the Second Amendment is unwavering and steadfast,” the company said. “Therefore, the company will not support any organization or event that prohibits the display or sale of legal firearms.”

After Connecticut passed new gun laws, Bartozzi accused Gov. Dannel Malloy of being “slanderous” and “using the industry as a straw man.” In 2014, CEO Iver Mossberg announced that most production would move to an existing factory in Texas. “It’s a state that is not only committed to economic growth,” he said, “but also honors and respects the Second Amendment and the firearm freedoms it guarantees for our customers.”

Founded in 1919 by Swedish immigrant Oscar Mossberg as a purveyor of a low-cost “pocket pistol,” O.F. Mossberg & Sons eventually focused on shotguns; today it is the world’s largest producer of pump-action models, including a line of Duck Dynasty-branded ones. But assault rifles drive the company’s growth. As Bartozzi has put it, “that’s what people want.”

The family keeps a low profile. Iver Mossberg lives in a relatively modest house in Branford, Connecticut. His father, former CEO Alan I. Mossberg, has retired to a Florida home originally built for the Swedish pop group ABBA. The Mossbergs may be more politically moderate than they let on. “I have had discussions with people who work for Mossberg, as well as [from] every other major gun company, who have actually indicated to me on a personal basis that they don’t have a problem with universal background checks,” Gov. Malloy told the New Haven Register in 2014, “but they are afraid of the NRA and they won’t stand up to it.”

Back in 1999, one of Alan Mossberg’s other sons, Jonathan, developed the iGun, a microchip-equipped shotgun that can only be fired by its owner. Though the company and other manufacturers later abandoned smart-gun technology under political pressure, Jonathan Mossberg recently revived the project as a separate enterprise and is courting Silicon Valley investors.

7. Savage

America’s largest maker of bolt-action rifles is owned by Vista Outdoor, a $2.9 billion holding company that also makes ammunition and gun accessories. After Newtown, Savage ran around-the-clock shifts to keep up with demand. Profits at Vista that year rose from $10 million to $64 million.

Mark W. DeYoung, who is CEO of both Vista and Savage, may be the nation’s highest-paid gun company executive, earning $13.2 million in 2015. He chairs the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, which lobbies on behalf of “America’s hunters and anglers,” and whose banquet was keynoted by soon-to-be Speaker of the House Paul Ryan in 2015. That same year, Vista Outdoor spent $390,000 on federal lobbying, mostly on bills concerned with defense appropriations and fishing and hunting. It also lobbied on the Toxic Substances Control Act, perhaps because in 2013 Massachusetts regulators fined Savage $6,000 for illegally dumping at least 50,000 gallons of industrial wastewater from its gun manufacturing operation into a sewer.

“I think 2016 is gonna be a strong year,” DeYoung told an NRA leader at a recent gun industry conference. “Election years always create some additional demand in our industry…So I suspect that will benefit us all, right?”

8. Springfield Armory

Current NRA President Allan Cors has boasted that of all the guns he owns, his favorite is the 1 millionth Springfield Armory M1 rifle, originally presented to its designer, John Garand, upon his retirement from Springfield Armory in 1953.

The company’s namesake dates to 1777, when George Washington approved the ammunition plant and arms depot as an arsenal for the Revolutionary War. The nationalized factory produced guns for American soldiers through World War II.

In 1974, the Springfield Armory name was licensed to Robert Reese, a surplus-store owner in Geneseo, Illinois. Despite the company’s slogan, “The First Name in American Firearms,” it now sources many of its guns from Croatia. Reese’s sons Dennis and Tom, the company’s current owners, nevertheless managed to help beat back a proposed Illinois ban on assault weapons by threatening to move the company’s factory across the river to Iowa.

In 1989, Dennis Reese admitted to offering bribes to US Army Colonel Juan Lopez de la Cruz—including $70,000 in cash and a Rolex watch—in exchange for help selling $3.7 million worth of firearms to the Salvadoran government. Reese was allowed to plead guilty to lesser charges in exchange for testifying against de la Cruz. But according to the Associated Press, the colonel walked after the jury decided Reese was not a trustworthy witness.

Over the years, Springfield has donated at least $1 million to the NRA.

9. Beretta

The 15-generation Beretta family claims to be the world’s oldest industrial dynasty. Their nearly 500-year-old company sits in a stone fortress surrounded by topiary gardens in a village near the Italian Alps. Napoleon and Mussolini were both big customers.

Patriarch Ugo Beretta and his wife, Monique, are members of the NRA Golden Ring of Freedom and have long cultivated political ties in the United States. At a 2010 dinner, their son Franco Gussalli Beretta presented George W. Bush with a $250,000 shotgun engraved with “43,” the presidential seal, and a picture of Bush’s Scottish terrier. The custom-made firearm was a thank-you for a US military order for half a million pistols. In 2014, Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam flew to Italy to meet with the Berettas. The company soon announced it would close its manufacturing headquarters in Maryland—where new gun control laws were fresh on the books—and relocate to Tennessee, where it got $14 million in subsidies.

Beretta markets guns as part of living the high life. There are Beretta-branded hunting lodges and a line of luxury clothing and home accessories. In cities including Dallas, Memphis, and New York, the Beretta Gallery offers après-field wear and specialty weapons, which have included $100,000 pistols decorated with diamonds.

At the family home in Italy, a liveried butler and cook oversee a mansion decorated with Venetian glass chandeliers, water buffalo heads, and elephant tusks. Franco Beretta drives a Maserati Quattroporte to visit the family’s commercial vineyards at their nearby 16th-century estate. Photos of his wife, Umberta, often appear in Italy’s society pages and on her fashion-obsessed Instagram account, where she recently appeared clutching a teddy bear made of cash.

10. Taurus International

In February 2015, Donald Simms, a ship captain in Alabama, was reloading his Taurus pistol at home when it unexpectedly fired. The bullet went through the palm of his hand and into the chest of his 11-year-old son, killing the boy. Simms sued the company, claiming a flaw in the gun’s internal safety mechanisms caused his son’s death. The suit is one of numerous cases alleging that Taurus pistols are dangerously defective. The company has recalled nearly 1 million pistols and settled a class-action lawsuit by setting aside $30 million for damages, court costs, and recall campaigns.

Taurus was founded 77 years ago as a tool manufacturer in Porto Alegre, Brazil; today, it earns roughly two-thirds of its gun revenue in the United States, where it offers free NRA memberships to purchasers. Nearly 87 percent of Taurus shares are owned by the Brazilian Cartridge Company, a gun and ammo manufacturer that was part of Remington before it was taken private in 2007 by investment funds tied to Daniel Birmann, one of Brazil’s most notorious securities fraudsters. In 2005, Birmann was fined the equivalent of $91 million by Brazilian regulators for bilking shareholders of an investment company he ran; in early 2015, Brazilian authorities seized a $23 million yacht that it claimed Birmann owned through shell companies based in overseas tax havens. Birmann’s family is believed to still control the Brazilian Cartridge Company’s Delaware-based holding company. Questions about quality control and a falloff in purchases from the Brazilian military and police have contributed to a 95 percent drop in Taurus’ share price since 2013.

Birmann, who splits his time between Porto Alegre and Rio de Janeiro, has been described in the Brazilian press as carrying a gun wherever he goes and paying cash at expensive restaurants. In 2005, the Brazilian pop singer Lobão filed a police report alleging Birmann assaulted him after he refused to play certain songs at the financier’s birthday party.

FIVE OTHER NOTABLE GUNMAKERS:

Keystone Sporting Arms

This Pennsylvania-based company markets the .22-caliber Crickett under the slogan “My First Rifle.” The blue and pink guns are proportioned for youth shooters and according to critics can appear toylike. In 2013 in Kentucky, a five-year-old playing with a Crickett accidentally shot and killed his two-year-old sister. A resulting flurry of national press put a spotlight on gun deaths of young children, which a Mother Jones investigation found are in the hundreds annually. Keystone also drew ire for online marketing to youth, including a “kids corner” page that featured photos of its guns being fired by tykes and cradled by babies. The company continues to publish cartoon “storybooks” and sells kid accessories such as a Crickett-wielding stuffed animal.

It’s all part of an industry effort to reverse a decline in shooting sports by exposing kids to guns at an early age. Sig Sauer now offers junior shooters a .22-caliber version of its AR-15. The National Shooting Sports Foundation encourages members to “help hunting and target shooting get a head start over other activities” by aiming “programs toward youth 12 years old and younger.” The NRA appeals to kids with stuffed animals and hunting video games at its annual conference, where gun companies have been known to hand out candy.

Kahr Arms

At the Shooting Industry Masters tournament in Kansas last year, participants dubbed the “Zoot Suit Shooters” dressed up like mobsters and blasted steel targets with Tommy Guns. It was a publicity stunt on behalf of Kahr Arms, maker of the Prohibition-era machine gun. The rights to the Tommy Gun were acquired in 1999 by Justin Moon, who started Kahr Arms in 1994 with a $5 million loan from his father—Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon.

Kahr Arms capitalized on the rising demand for powerful yet small handguns when concealed-carry laws began sweeping the nation in the 1990s. Its K-9 pistol was small enough to fit into a pants pocket. Emergency room physicians blamed the spread of this type of gun from Kahr and other companies for a dramatic rise in fatal gunshot wounds.

Growing up in the suburbs of New York, Justin Moon “would always philosophize about the world ending and how great his father was,” Tim Porter, the son of high-ranking church members, told Condé Nast Portfolio in 2007. “That’s why he did all this stuff with guns. He believes that [the Unification Church] is going to take over the world. He would say this all the time.”

Barrett Firearms

In April 2013, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie called for a ban on the .50-caliber Barrett M82 and M107 sniper rifles—and then vetoed the bill four months later. He claimed it went further than he’d intended by prohibiting current owners from keeping the weapons, which are powerful enough to down helicopters, pierce bulletproof glass, or kill from a mile away. In the middle of debate over the bill, Christie’s campaign accepted $3,000 from an NRA lobbyist.

Barrett’s CEO, Ronnie Barrett, sits on the NRA’s board of directors. Once a professional wedding photographer, he resides on a 17-acre plantation-style estate in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, that features an 11,000-square-foot mansion and a formal English garden. According to the Government Accountability Office, Barrett’s .50-caliber rifles have been used by drug cartels, militia groups, outlaw motorcycle gangs, and terrorist organizations. The Branch Davidians wielded one during the 1993 Waco siege in Texas, forcing federal agents to use armored Bradley fighting vehicles. California and Washington, DC, have banned the guns, but they remain legal everywhere else. In February, the Tennessee Senate passed a resolution designating the Barrett M82 the official state rifle.

Norinco

Headquartered in Beijing, Norinco makes shotguns sold mostly through online dealers such as CheaperThanDirt.com. It imports tens of thousands of guns into the United States each year. Owned by China’s Communist Party, the company provides weapons to the People’s Liberation Army and military clients that have included the government of South Sudan. The company also produces hydroelectric equipment, subway cars, and raw copper. In 2003 it was accused of transferring missile technology to Iran, prompting a two-year US import ban.

Hi-Point Firearms

When Hi-Point founder Tom Deeb learned in 1999 that one of his company’s semi-automatic rifles had been used in the Columbine mass shooting, he closed his factory for a day. “I was just sick over it,” he told the Buffalo News. “I thought about quitting.” But then he changed his mind, deciding, “I’m not going to be defeated by evil.” (The company began to expand its use of serial numbers.)

Hi-Point, whose handguns have retailed for as little as $79, was long one of the most notorious suppliers of so-called “Saturday night specials.” In 2000, Hi-Points were the third most common type of gun seized at crime scenes in 44 cities, according to the ATF. On average, Hi-Points reached criminals within a year of their original purchase, making them among the quickest guns to flow into the black market.

In 2005, the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence sued the company on behalf of Daniel Williams, a 16-year-old who was mistaken for a gang member and shot while playing basketball. The suit alleges that the company and its sole distributor were negligent in selling the pistol—along with 86 other guns—to a straw purchaser at a gun show. A judge tossed out the case under the 2005 shield law. In 2012 an appeals court reinstated the case, which remains in a New York court.

Additional reporting by Bryan Schatz and Dave Gilson