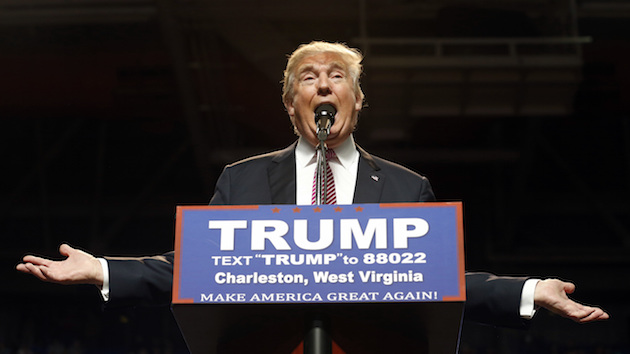

David Goldman/AP

On Monday evening, California’s secretary of state published a list of delegates chosen by the Trump campaign for the upcoming Republican presidential primary in the state. Trump’s slate includes William Johnson, one of the country’s most prominent white nationalists. [Update: Responding to this story late Tuesday, the Trump campaign blamed Johnson’s selection on a “database error,” and Johnson told Mother Jones he would resign. Here are documents showing the Trump campaign’s personal correspondence with Johnson yesterday.]

Johnson applied to the Trump campaign to be a delegate. He was accepted on Monday. In order to be approved he had to sign this pledge sent to him by the campaign: “I, William Johnson, endorse Donald J. Trump for the office of President of the United States. I pledge to cast ALL of my ballots to elect Donald J. Trump on every round of balloting at the 2016 Republican National Convention so that we can MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!” After he signed, the Trump campaign added his name to the list of 169 delegates it forwarded to the secretary of state.

Johnson leads the American Freedom Party, a group that “exists to represent the political interests of White Americans” and aims to preserve “the customs and heritage of the European American people.” The AFP has never elected a candidate of its own and possesses at most a few thousand members, but it is “arguably the most important white nationalist group in the country,” according to Mark Potok, a senior fellow for the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which tracks hate groups.

Johnson got the news that he had been selected by Trump in a congratulatory email sent to him by the campaign’s California delegate coordinator, Katie Lagomarsino. “I just hope to show how I can be mainstream and have these views,” Johnson tells Mother Jones. “I can be a white nationalist and be a strong supporter of Donald Trump and be a good example to everybody.”

Johnson says that in his application to be a delegate for Trump he disclosed multiple details about his background and activism, though he did not specifically use the term “white nationalist.” The Trump campaign and Lagomarsino did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Whether or not Johnson was vetted by the Trump campaign, the GOP front-runner would have a hard time claiming ignorance of Johnson’s extreme views: Johnson has gained notice during the presidential primary for funding pro-Trump robocalls that convey a white nationalist message. “The white race is dying out in America and Europe because we are afraid to be called ‘racist,'” Johnson says in one robocall pushed out to residential landlines in Vermont and Minnesota. “Donald Trump is not racist, but Donald Trump is not afraid. Don’t vote for a Cuban. Vote for Donald Trump.”

Armed with cash from affluent donors and staffed by what the movement considers to be its top thinkers, the AFP now dedicates most of its resources to supporting Trump. Johnson claims that the AFP’s pro-Trump robocalls, which have delivered Johnson’s personal cellphone number to voters in seven states, have helped the party find hundreds of new members. “[Trump] is allowing us to talk about things we’ve not been able to talk about,” Johnson says. “So even if he is not elected, he has achieved great things.”

On multiple occasions, Trump has failed to forcefully repudiate this sort of support. After being endorsed by former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke in August last year, Trump told Bloomberg News, “I don’t need his endorsement; I certainly wouldn’t want his endorsement. I don’t need anybody’s endorsement.”

Asked in February about the robocalls, which are funded by Johnson through a super-PAC, a Trump spokeswoman would only tell CNN that the candidate had “disavowed all super-PACs offering their support.” In April, the Huffington Post reported that Trump returned a $250 donation to his campaign from Johnson.

The SPLC’s Potok says Trump has “legitimized and mainstreamed hate” in ways we haven’t seen since the days of George Wallace. Though nobody can say for sure how many people belong to America’s largest hate groups, the SPLC has found that the number of such groups grew by 14 percent in 2015, reversing years of declines. Potok worries that Trump could fuel the spread of the AFP’s ideas for years to come.

Johnson is a corporate lawyer who grows persimmons and raises chickens at his 67-acre “ranch” in a Los Angeles suburb. When I met him recently outside his law office in downtown LA’s World Trade Center, he was in high spirits. He suggested brightly that we walk downstairs to get lunch at a nearby Korean restaurant. As we sat next to a table of immaculately coiffed Korean Air flight attendants, I mentioned that some might find it surprising that a guy who wrote a book advocating the creation of an all-white ethno-state was eating a plate of bulgogi beef with kimchee. “Koreans don’t have to make Korean food,” he said matter-of-factly. “One of the best Chinese restaurants I went to in the Bay Area is owned by a Mormon and cooked by a Mormon. Really great Chinese food.”

Short, graying, and 61 years old, Johnson favors pressed white shirts and bookish black-framed glasses. He grew up in predominantly white neighborhoods in Arizona and Oregon before moving to Japan in 1974 to study the language. It was there that locals engaged him in “open” discussions about differences between the races, and he came to see America’s European heritage as its biggest—and most vulnerable—asset. (This trajectory is not uncommon: Jared Taylor, head of the white nationalist group American Renaissance, also speaks fluent Japanese, and Aryan Nations founder Richard Butler became a white supremacist while immersed in the caste system in India.) In 1985, Johnson published, under a pseudonym, Amendment to the Constitution: Averting the Decline and Fall of America, a book calling for the abolition of the 14th and 15th Amendments and the deportation of all nonwhites. He tried to sound a practical tone, allowing, for instance, that African Americans should receive “a rich dowry to enable them to prosper in their homeland.”

The book was a hit on the talk show circuit, and Johnson suddenly found himself appearing on television alongside neo-Nazi skinheads and Klansmen. By 1989, his notoriety and clean-cut appeal convinced a group of white nationalists in Wyoming to tap him to run for Dick Cheney’s vacant congressional seat. He garnered a flurry of press coverage when he earned enough signatures to qualify for the ballot; around the same time, the building housing his California law office was bombed. Johnson says the FBI accused him of detonating it himself in a bid for more press. (The bureau declined to comment.)

Twenty years later, after unsuccessfully running for various other offices, Johnson became the head of the American Freedom Party (then known as American Third Position), at the request of a group of Southern California skinheads. Johnson’s post was supposed to be temporary: “The skinheads thought I was too extreme to run the organization,” he explained. But they were the ones who ended up dropping out, replaced by what has become a sort of white nationalist brain trust: Party leaders now include a former Reagan administration appointee and a professor emeritus at California State University-Long Beach.

After our Korean lunch, Johnson rushed back up to his office to host the latest episode of For God and Country, a Christian AM talk show currently broadcast in California, Louisiana, and Texas. His Filipino American co-host, the Rev. Ronald Tan, nodded approvingly as Johnson praised Trump on the air for “busting up the concept of political correctness.”

The show allows Johnson to push a Trump-centric version of white nationalism to a potentially receptive audience—up to a point. Several radio stations in Iowa recently canceled the program out of objection to its content. During a commercial break, Johnson fidgeted. “Are you going to quote any more Scriptures?” he asked Tan nervously. “Has the station said that we’re not Christian enough?” Back on the air, Tan pivoted to 1 Samuel 16, comparing Trump to King David.

In addition to promoting Trump on the radio and over the phone, the AFP streams a podcast called the Daily Trump Phenomenon Hour. It has set up a “political harassment hotline” for Trump supporters who wish to consult with an attorney about being attacked or verbally abused by anti-Trump protesters. Johnson has personally spent $30,000 on the Trump promotions, including $18,000 for the robocalls.

The robocalls, the radio show, and the “harassment hotline” were all things that Johnson mentioned in his application to become a Trump delegate. He specifically cited an anti-Romney robocall commissioned in Utah this past March, which begins, in part, “My name is William Johnson. I am a farmer and a white nationalist.”

After wrapping up the radio show, Johnson led me through his office, where a brush-painted screen hangs alongside shelves stacked with Japanese books and dictionaries. Many of his legal clients, it turns out, are foreigners who speak English as a second language. Yet Johnson says he sees no problem with Trump’s isolationist foreign policy, even if it hurts his business—ideally, he’d like to give up his practice and serve as Trump’s secretary of agriculture.

We ended up in a mirrored conference room to meet with three AFP sympathizers, two middle-aged women and a young man. They talked about how Trump had enabled a new kind of “honest discourse,” how he wasn’t a racist but a “racialist,” and how he had left them feeling “emancipated.” Johnson also now finds it easier to be himself: “For many, many years, when I would say these things, other white people would call me names: ‘Oh, you’re a hatemonger, you’re a Nazi, you’re like Hitler,'” he confessed. “Now they come in and say, ‘Oh, you’re like Donald Trump.'”