It isn’t just ourselves or our pets that have been getting bigger over the past couple of decades. Turns out, our beef cows have become gigantic too. How big? According to an excellent article by Melody Petersen in the Chronicle of Higher Education, “the average weight of a fattened steer sold to a packing plant is now roughly 1,300 pounds—up from 1,000 pounds in 1975.”

That’s a hefty 30 percent gain. What gives? According to Peterson, the main reason is pharmaceutical: heavy use of antibiotics, hormones, and other growth-enhancing drugs. Peterson untangles the web that connects pharmaceutical giants like Merck to professors at big public land-grant universities, who not only act as paid researchers to develop new products but also as shills who appeal directly to cattle feedlot operators.

Peterson shows that as public funding for agriculture research has leveled off, private interests, including pharma companies, have rushed to fill the void, pumping billions of dollars in grants each year to public ag-science departments. Overall, according to a chart at the bottom of the story, federal R&D funds for ag research has leveled off at about $5 billion, while private fundiung rose steadily and now hovers around $6 billion (both figures in 2006 dollars to adjust for inflation). What could possibly go wrong? Peterson lays it out:

In certain ways, the close relationship between animal scientists and pharmaceutical companies has never served the public well. Few animal scientists have been interested in looking at what harm the livestock drugs may be causing to the cattle, the environment, or the people eating the meat. They’ve left most of that work to scientists outside of agriculture, consumer groups, and others who take interest.

She paints a devastating picture: Public universities that have given up the pretense of serving the public interest and have instead have lapsed into research and (to an extent) marketing arms of large corporations. A similar dynamic holds for human-related medical research, Peterson notes, but the situation is even more stark in the livestock research world.

Yet unlike a growing number of medical schools around the country, where administrators have recently tightened rules to better police their faculty’s ties to pharmaceutical companies, the schools of agriculture have largely rejected critics’ concerns about industry cash. Administrators have set few limits on how much corporate money agricultural professors can accept. Faculty work with industry is governed by confidentiality rules that veil it from public view.

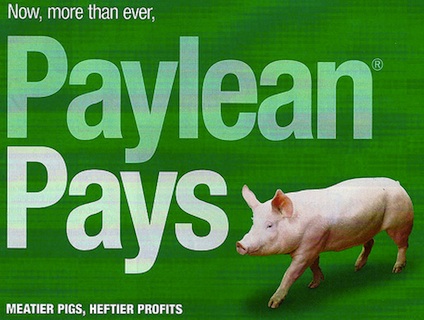

Peterson focuses on Merck’s Zilmax drug, which causes cows to bulk up quickly. Zilmax, Peterson reports, is what’s known as a beta-adrenergic agonist—a class of drugs that make animals put on lean muscle weight, but also causes them stress. Another beta-adrenergic agonist, pharma giant Elli Lilly’s ractopomine, is widely used to fatten hogs. Several countries, including Taiwan, China, and the members of the European Union, have banned these chemicals. Some refuse to import meat from animals that have been treated with it, causing trade tensions with the US.

Interestingly, Zilmax seems to serve no one’s interest besides Merck’s and the scientists in its hire. Peterson reports that gigantic beef processors like Cargill, which buy cows from feedlots for slaughter, want nothing to do with it, not only because the gigantic cows it produces lead to unwieldy beef cuts, but also because the resulting meat is tough and flavorless. Perhaps to overcome this resistance from industry, Merck is pushing ag scientists to convince farmers it’s in their interest to use the drug. One of the main researchers Peterson highlights, West Texas A&M University professor Ty E. Lawrence, touts the growth-enhancing effects of Zilmax to feedlot operators without mentioning that some processors reject cows that have been treated with it, Peterson reports.

Trouble with the processor isn’t the only factor that gives feedlot operators pause.

While products that make the cattle grow bigger increase the price that ranchers can get for their herds, the ranchers fear that the added expense of the drugs, as well as the cost of the extra feed that bigger cattle require, will leave them with no additional profit, or even with a loss.

Why would a pharma company expend resources promoting such a dud of a product? Likely, the company is trying hard to recoup the investment it took to develop Zilmax in the first place.

As for the cows themselves, being dosed with Zilmax sucks, especially in hot weather. Peterson reports that the animal-welfare expert and Colorado State University professor Temple Grandin has found that Zilmax and a rival beta-adrenergic agonist, Eli Lilly’s Optaflexx (the bovine version of its ractopamine), causes cows to go lame in the heat.

In effect, the pharmaceutical industry is producing drugs that make animals sick, not well—and enlisting academics to promote their dubious products.

The larger story here is what might be thought of as the leveraged buyout of public-university ag-science programs by corporate interests. Land-grant universities were founded in the 19th century to conduct farming research to benefit the broad public. Today, their animal-ag departments could be focusing on, say, innovative systems for raising cattle on pasture in rotation with crops, which would require less fertilizer, produce healthier cows and meat, and help sequester climate-heating carbon. Such research builds skill and knowledge among farmers—and doesn’t doesn’t require them to buy any products.

And that’s precisely why such research been orphaned in today’s land grant institutions —there’s no big company clamoring to fund it. As a result, our public animal-ag programs are focused narrowly on fattening cattle as fast as possible—and fattening the bottom lines of their Big Pharma sponsors.