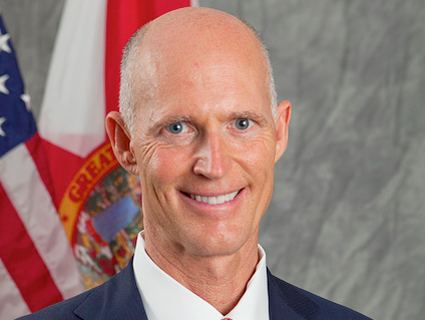

<a href="http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/09/Rick_Scott_official_portrait.jpg">Wikimedia</a>

Last year, political neophyte Rick Scott spent $73 million of his own money to bring the tea party’s anti-government, pro-privatization agenda to the Florida governor’s office. Today, the former executive pays just $30 a month for health care—and lets taxpayers cover the rest.

The governor, a proud bearer of the Republican Party’s deregulation standard, has spent his first half-year in office decrying government waste: He’s laid off thousands of Sunshine State employees, slashed their benefits, turned down (most of) the federal government’s health care dollars, and put extra financial pressure on Florida retirees and Medicaid recipients. But Scott and his dependents pay one-fifth what a janitor in the state Capitol pays for health insurance…and less than 3 percent of what a retired state trooper pays for life-saving coverage.

When asked about the double standard, a spokesman for Scott declined to comment, calling his family’s cheap state coverage “private matters.“

But the matter has huge implications for citizens of the state. Scott sits atop an upside-down benefits system that heavily subsidizes health care costs for the best-off state employees while forcing loyal rank-and-file workers to spend more of their shrinking paychecks for basic coverage. According to Gary Fineout, the longtime Tallahassee reporter who broke the story:

Scott is among nearly 32,000 people in state government who pay relatively low health insurance premiums. It’s a perk that is available to high-ranking state officials, including those in top management at all state agencies. Nearly all 160 state legislators are also enrolled in the program that costs just $8.34 a month for individual coverage and $30 a month for family coverage.

Florida’s elected politicians, judges, attorneys, prison wardens, department heads, and political staffers are members of the “special exempt service,” which allows their cozy incomes to be augmented by the extra health care subsidy. But most of Florida’s 176,816 insured state employees (PDF) are members of the “career service” and pay (PDF) $50 a month to cover themselves, or $180 a month to cover their families.

That means a $32,000-a-year administrative assistant for the driver’s license bureau pays $2,160 a year for herself and her dependents, or more than five times what Scott pays. (As of last month, Scott—who moved to Florida eight years ago—had a net worth of $103 million.)

State workers could have it worse, though. Retired Florida government employees—30-year veterans of the state’s police force, or firefighters, for example—get no subsidy from Tallahassee to keep their coverage in the golden years. Instead, they pay $1,243.34 a month, or nearly $15,000 a year, to stay insured. That’s 41 times what Scott’s health insurance costs.

So who pays to give Scott and his cronies their cut-rate coverage? Taxpayers do. It’s not clear how many of the state’s 32,000 top-ranking VIPs cover themselves, and how many get their entire families on the state plan. Depending on that breakdown, Floridians are paying between $1.3 and $4.8 million every month to extend this perk to their political elites. That could amount to as much as $57.6 million a year—12 times what the state spent on public broadcasting before Scott decided to defund the radio and TV stations, calling them “a special interest.“

News of the governor’s health care perk comes just as he’s attempting to improve his image and boost his national profile. Last week, Scott revived a Democratic predecessor’s tradition of spending an occasional day working alongside regular Floridians; his first foray, handling the counter of a Tampa doughnut shop, brought scads of protesters but generally positive coverage. Public approval of the governor rose to an anemic 35 percent last week—still better than his low of 29 percent in May, the worst of any governor in the nation. And Scott’s also taken a leading role in supporting erstwhile GOP presidential candidate Rick Perry. (“I think he’s in a nice position,” Scott said of the hardline Texas governor.)

If Scott hopes to climb all the way out of the political cellar, though, he’s going to have to explain why he favors government health care for his kin even though he’s against it for everyone else. State Sen. Nan Rich, a Democrat, told Fineout that the governor is clearly “entitled” to his insurance subsidy, as far as the law is concerned. But, she added, “I wish every Floridian had the same opportunity.”