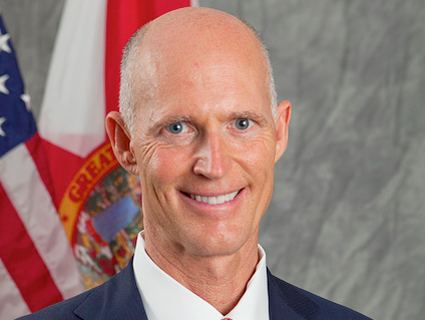

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/publik15/4440720319/">Publik15</a>/Flickr

Florida’s neophyte Republican governor, tea-party-friendly Rick Scott, signed a bill back in June requiring the state’s welfare recipients to undergo drug-testing urinalysis before collecting their monthly assistance check of around $241-to-$303. The measure, he said, would save taxpayer money by barring drug addicts from getting the dole. “Studies show that people that are on welfare are higher users of drugs than people not on welfare,” he said.

Florida’s welfare recipients are proving that Scott’s assumption wasn’t worth a warm bucket of pee. Now, the state is effectively being forced to pay for 11.5 gallons of welfare applicants’ drug-free urine every month, to the tune of around $34,000.

Of the 1,000 or so recipients who have taken the required drug tests (at their own expense) since early July, only 2 percent have tested positive for drugs, according to the Tampa Tribune. That’s well below the national population’s average, and it’s so low that the testing plan—which was expected to cost $187 million by some analysts’ estimates—could end up costing taxpayers even more in the long run.

The way it was supposed to work, according to Scott and other supporters, was this: Everyone who took the test at a state-approved private lab (PDF) would have to pay for it out of pocket. (Never mind where a poor Floridian is supposed to scrape together 25 to 30 percent of their monthly benefit on their own.) If they tested negative for illegal drugs, they’d be reimbursed for the urinalysis, anywhere from $10 to $82, in their welfare check. Drug addicts would be out the testing cost and barred from receiving benefits for a year. The theory, then, was that the presumably huge population of drug-addled free riders would be kicked off the bus, and Florida would reap the savings. (The plan was briefly held up when it came to light that a health care firm started by Scott, Solantic, could get a contract for the urinalysis.)

But with 96 percent of applicants passing the test with flying colors (and another 2 percent getting inconclusive results), the state is having to buy back a lot of clean pee: 11.5 gallons at $34,300 every month, assuming an average sample size of 1.5 ounces and and average test price of $35. Not only that, but Florida’s rules allow parents who fail the test to designate another adult who can collect the benefits on behalf of any dependent children. And since the state’s welfare program is oriented toward families, it seems likely that most of the failures’ benefits will still be paid out to someone. (Given the scarce numbers offered by the Florida Department of Children and Families, it’s also not immediately clear whether the amount of applicants for assistance changed significantly after the whiz quizzes were instituted.)

Local reporters around the state have run smaller investigations and found the economics to be grim. TV station WFTV found that 40 applicants were tested in Central Florida, and two popped positive for drugs. The testing cost to taxpayers was at least $1,140; the theoretical savings in benefits to the two who failed was $240—at most. “We have a diminishing amount of returns for our tax dollars,” ACLU spokesman attorney Derek Brett, an opponent of the drug plan, told WFTV.* “Do we want our governor throwing our precious tax dollars into a program that has already been proven not to work?”

The Tribune engaged in some creative accounting to show that the testing program could still show a modest net savings on benefits payments, of roughly $40,000 to $60,000 a year in total, or half of what most senior staffers in Gov. Scott’s office make. But that doesn’t take into account the state’s costs to process the test results and administer the program, which nobody seems to know yet—least of all the governor who sold state residents on the idea. “We don’t have a dollar cost estimate at this time,” Scott’s spokesman said on June 6…five six days after Scott signed the bill into law.* (Interestingly, Florida requires all state ballot initiatives to be accompanied by an estimate of the proposals’ financial impacts; Scott and the Legislature, though, don’t have to do any such calculations for their bills.)

Despite Florida conservatives’ miscalculations—miscalculations that critics say are based on bogus stereotypes—many states are considering following its lead on drug tests for welfare applicants. Last spring, Idaho’s Legislature commissioned a study on the subject, which found that the plan would end up costing more than it took in.

But then, Idaho analysts also assumed the state would put its failures in publicly financed drug-counseling programs. By contrast, Florida’s welfare information site stresses that the state “does not pay or reimburse for the cost of drug treatment programs.”