<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/adwriter/339057805/sizes/z/in/photostream/">adwriter</a>/Flickr

In The New Republic this week, Jon Cohn has an eye-opening piece, “The Two Year Window,” about advances in the science of early childhood development. It opens with a description of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, a study that removed infants from warehouse-style orphanages in Romania and adopted them out:

It was ten years after the fall of the Communist dictator Nicolae Ceau?escu, whose scheme for increasing the country’s population through bans on birth control and abortion had filled state-run institutions with children their parents couldn’t support…. The new government remained convinced that the institutions were a good idea—and was still warehousing at least 60,000 kids, some of them born after the old regime’s fall, in facilities where many received almost no meaningful human interaction. [Neuroscientist Charles Nelson] prevailed upon the government to allow them to remove some of the children from the orphanages and place them with foster families. Then, the researchers would observe how they fared over time in comparison with the children still in the orphanages.

…Prior to the project, investigators had observed that the orphans had a high frequency of serious developmental problems, from diminished IQs to extreme difficulty forming emotional attachments. Meanwhile, imaging and other tests revealed that some of the orphans had reduced activity in their brains. The Bucharest project confirmed that these findings were more than random observations. It also uncovered a striking pattern: Orphans who went to foster homes before their second birthdays often recovered some of their abilities. Those who went to foster homes after that point rarely did.

This past May, a team led by Stacy Drury of Tulane reported a similar finding—with an intriguing twist. The researchers found that telomeres, which are protective caps that sit on the ends of chromosomes, were shorter in children who had spent more time in the Romanian orphanages….It was the clearest signal yet that neglect of very young children does not merely stunt their emotional development. It changes the architecture of their brains.

…”The concept of disrupting brain circuitry is much more compelling than the concept that poverty is bad for your health,” says Jack Shonkoff, a Harvard pediatrician and chair of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. “It gives us a basis for developing new ideas, for going into policy areas, given what we know, and saying here are some new strategies worth trying.”

What’s new here isn’t really the idea that experiences in early childhood are important. In fact, in the era following the Second World War, the idea that habits established early in life are permanent was, if anything, belabored too much. “If mothers did not nurture their infants properly,” Jerome Kagan wrote in 1999, criticizing this widespread belief, “their children would be vulnerable to a dull mind, a wild spirit, and a downward spiral…This view of development rests on the assumption that every experience produces a permanent physical change somewhere in the central nervous system, and therefore the earliest experiences provide the scaffolding for the child’s future thought and behavior.”

What Kagan was criticizing, though, was primarily the idea that particular styles of parenting were necessary to produce well-adjusted children. Generally speaking, that turns out not to be true: You don’t need to play Mozart to your baby or jump through hoops to make sure she’s properly “attached.” Most middle-class kids turn out okay even though they’re exposed to a wide variety of parenting styles.

But Cohn’s piece is about something different: It’s about kids whose infancy is, to put it bluntly, fairly appalling. And not just in warehouses in Bucharest. Diana Rauner visited child care facilities in Chicago while she was working on her doctoral dissertation and “described facilities where infants were strapped in car seats, ‘watching The Lion King all day,’ while the older kids were ‘circling the room almost like sharks’ and throwing things at the infants, because they had nothing else to do.” That kind  of environment, it turns out, can cause permanent cognitive damage, sometimes at a biological level, and it’s probably a lot more common than you think.

of environment, it turns out, can cause permanent cognitive damage, sometimes at a biological level, and it’s probably a lot more common than you think.

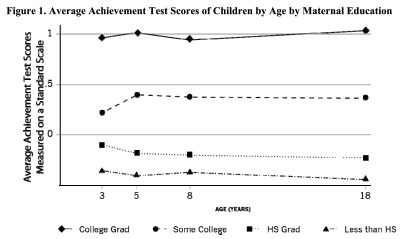

You can see more of the evidence for the importance of early childhood in the chart on the right, which I posted earlier this year. It comes from James Heckman, probably the preeminent researcher in this area, and it shows average achievement test scores for different classes of children. All show the exact same dynamic: Gaps show up as early as age three and persist pretty much forever. Some of this is due to genetic differences, but not all of it. It’s also due to differences in children’s early environments. The lesson is simple: If you want to have a real impact on how kids do in school, you have to get to them early.

But even this understates the benefit of intensive early interventions. The payoff, in general, doesn’t come in higher test scores, anyway. A large and growing body of research suggests that it comes in other behaviors: for example, the ability to delay gratification, the ability to hold a job, the ability to control your temper, and the ability to stay away from drugs and alcohol.

The problem, of course, is that early intervention costs money. Lots of money. According to Cohn, we currently spend about $11,000 per student in K-12 and about $4,000 per child under the age of four. That’s crazy. But if we wanted to equalize that spending, how could we do it? One option is just to raise more money. But if we spent $11,000 for every child under the age of four, that would come to over $100 billion per year in new spending. There’s no way that’s going to happen.

Another option would be to take the pot of money we already spend and equalize it: spend about $9,000 per child all the way from ages 1-18. Unfortunately, this is hardly any more likely: If we tried to reduce the amount we spend on K-12, teachers unions would go ballistic, ed reformers would go ballistic, and suburban parents would go ballistic. If I were a benevolent dictator, I’d do it anyway, because it would almost certainly be a far better use of our existing money. But I’m not, am I?

Still, this is an area that cuts across party lines and deserves far more attention than it gets. The evidence has been mounting for a long time that intensive early interventions produce a huge bang for the buck, far more than what we spend in primary and secondary schools. The problem is that the bucks have to be spent now, and the bang doesn’t arrive for another decade or two. Where’s Bill Gates when you need him?