Allison V. Smith/New York Times/ReduxIf there’s a controversial new anti-immigration law that’s captured national attention, chances are that it has Kris Kobach’s imprimatur. A telegenic law professor with flawless academic credentials—Harvard undergrad, Yale Law School—Kobach helped Arizona lawmakers craft the infamous immigration law that passed in the spring of 2010. He’s coached legislators across the country in their efforts to pass dozens of similar measures, ranging from Alabama, Georgia, and Missouri to the small town of Fremont, Nebraska, pop. 26,000. His record has helped propel him into elected office, becoming Kansas’ secretary of state just six months after the passage of Arizona’s SB 1070.

Allison V. Smith/New York Times/ReduxIf there’s a controversial new anti-immigration law that’s captured national attention, chances are that it has Kris Kobach’s imprimatur. A telegenic law professor with flawless academic credentials—Harvard undergrad, Yale Law School—Kobach helped Arizona lawmakers craft the infamous immigration law that passed in the spring of 2010. He’s coached legislators across the country in their efforts to pass dozens of similar measures, ranging from Alabama, Georgia, and Missouri to the small town of Fremont, Nebraska, pop. 26,000. His record has helped propel him into elected office, becoming Kansas’ secretary of state just six months after the passage of Arizona’s SB 1070.

Kobach routinely denies that he’s the progenitor of the anti-immigration laws he’s drafted or defended. Rather, he insists he simply assists officials already committed to tougher enforcement policies. “I did not generate the motivation to pass the law…I am merely the attorney who comes in, refines, and drafts their statutes,” he says.

But advocates on both sides of the immigration debate agree that Kobach’s influence has been far-reaching. Rosemary Jenks of NumbersUSA, an anti-immigration group, calls Kobach “instrumental in helping states and localities deal with the federal government’s authority.” Vivek Malhotra, a lawyer who worked for the American Civil Liberties Union when it tussled with Kobach in court, says, “What Kris Kobach has done as a lawyer is really gone out to localities around the country and really used them as experimental laboratories for pushing questionable legal theories about how far states and local governments can go.”

Kobach, 45, has spent much of his professional life developing the legal framework that a growing number of officials have used to justify laws further criminalizing illegal immigration. A rising star in the Republican establishment, Kobach joined John Ashcroft’s Justice Department just days before 9/11. Over the next two years, he helped create a program that required all visiting citizens from 25 mostly Arab countries to be fingerprinted and monitored—a policy that critics said amounted to racial profiling.

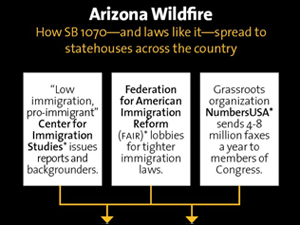

See the rest of the flowchart.During those years, Kobach advanced an idea that had long been circulating in conservative legal circles: that local and state officials have the “inherent authority” to enforce federal immigration laws. This unorthodox notion bucked the prevailing view—long held by both Republican and Democratic administrations—that the federal government has principal jurisdiction over immigration under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution. If local and state governments were to strike out on their own, they could undermine federal efforts, create jurisdictional chaos, and detract from law enforcement efforts by discouraging immigrants from cooperating with police, critics argue. In 2002, however, Ashcroft’s Office of Legal Counsel issued a memo, which Kobach helped review, supporting the “inherent authority” theory.

See the rest of the flowchart.During those years, Kobach advanced an idea that had long been circulating in conservative legal circles: that local and state officials have the “inherent authority” to enforce federal immigration laws. This unorthodox notion bucked the prevailing view—long held by both Republican and Democratic administrations—that the federal government has principal jurisdiction over immigration under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution. If local and state governments were to strike out on their own, they could undermine federal efforts, create jurisdictional chaos, and detract from law enforcement efforts by discouraging immigrants from cooperating with police, critics argue. In 2002, however, Ashcroft’s Office of Legal Counsel issued a memo, which Kobach helped review, supporting the “inherent authority” theory.

After leaving the Bush administration in 2003, Kobach joined the Immigration Reform Law Institute and began working with local officials across the country to combat illegal immigration on the ground level. He also pitched in as a defense attorney when such measures were challenged in court, defending legislation in Pennsylvania and Texas that would revoke operating licenses for businesses that hired illegal immigrants and fine landlords who rented to them. In 2006, he landed his first major gig in Arizona, hired by state officials to defend a law that made immigrant smuggling a state crime.

Kobach has worked hard to develop laws that can withstand court challenges. “[Arizona SB 1070] was very carefully crafted to track many provisions in federal law—it creates a plausible case for proponents to say we’re not doing anything new,” says Mary Giovagnoli, director of the Immigration Policy Center. “It’s a disingenuous argument, to say if it’s illegal in the federal law, it’s okay when it’s illegal in state law…but it’s very clever lawyering.” In fact, Kobach scored a big victory last year when the Supreme Court upheld a separate Arizona law he helped craft that punished employers who hired illegal immigrants.

That said, Obama’s Department of Justice has aggressively challenged the major laws that Kobach has helped author. In addition to filing lawsuits against the Arizona and Alabama laws, the DOJ has taken action against Arizona’s Sheriff Joe Arpaio, whose officers Kobach helped train in immigration enforcement. In December, Arpaio’s officers were forced to hand in their federal credentials due to complaints about their immigration enforcement tactics, which the DOJ called illegal and discriminatory.

But such legal challenges haven’t slowed down Kobach, who has endorsed Mitt Romney and provided the candidate his immigration talking points. In his first year in office as secretary of state, he successfully shepherded through a new Kansas voter ID law, claiming that the current laws allowed immigrants to commit voter fraud—a new front in the immigration wars that parallels the conservative push for stricter voting laws. He’s now advising Kansas legislators on a bill that would give local police far more latitude in checking the status of suspected illegal immigrants—effectively bringing Arizona’s law to his own backyard.