Image: Andreanna Lynn Seymore

Five clumps of pens, rubber-banded together, spill from an overstuffed envelope to the floor of Dr. Bob Goodman’s office. Each ball point bears the name of a different blockbuster drug — Lipitor, Paxil, Zocor. They have been sent in by a doctor who’d learned about Goodman’s one-man organization, No Free Lunch, and its “Pen Amnesty” program: Turn in your collection of industry-supplied freebies, and Goodman will send back a few replacement pens bearing the No Free Lunch insignia. “It’s a money loser,” Goodman says, “but it’s a fun way to spread the word.”

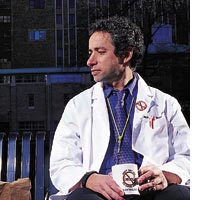

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the pharmaceutical industry spends $8,000 to $13,000 per physician each year to promote its wares, which are hawked by a sales force of roughly 80,000 representatives. “If you randomly look at a doctor’s white coat, you’ll see a stethoscope tag with one drug company’s name on it,” says Goodman, an internist who also teaches at Columbia University’s medical school. “Then there are several pens in their pockets, and calipers, each with a drug company’s name. We’re walking advertisements.”

The ubiquity of perks has bothered Goodman since his med-school days in the late 1980s, when he felt uneasy eating pizzas supplied by drug salesmen. In 1999, Goodman was opening a new clinic for low-income patients in the Washington Heights neighborhood of upper Manhattan. He decided to keep the clinic off-limits to drug sales representatives, but that meant cutting off access to the free drug samples doctors often give to patients who don’t have medical coverage. “So I decided I was going to make up some pens and mugs in order to raise money to buy meds for patients,” says Goodman. He created a website to sell the items, called it NoFreeLunch.org, and included some salient figures on the industry’s marketing excesses. The site now attracts roughly 300 visitors a day, and well over 1,000 pens have been turned in.

Maryann Napoli, associate director of the Center for Medical Consumers, a nonprofit dedicated to drug-marketing reform, says it’s crucial for doctors and patients to see that not all health care providers are comfortable with corporate gifts. “I find [No Free Lunch] to be one of the few hopeful things in this area,” she says. “So many doctors are now bought and paid for.”

Though bad press has forced drug companies to scale back some of their more extravagant gifts, like the Caribbean getaways of yore, Goodman says expensive dinners, and tickets to Broadway shows and big-league games remain commonplace. One popular sales technique involves trailing a doctor to a gas station, then offering to pay for a lube job — during the wait at the shop, the sales representative has ample time to talk up his product. Then there are the more lavish perks, like dinner and complimentary rooms at New York’s Plaza Hotel; as the Washington Post reported last year, doctors who attended one such gala were also handed $500 checks from the event’s sponsor, Forest Laboratories.

“Doctors take such umbrage when you suggest that [the perks] influence what they prescribe,” says Goodman. “But of course they do — otherwise, they wouldn’t be given out.” Indeed, numerous studies have shown that perks and meals nudge physicians toward prescribing certain drugs, even when better and less expensive options are available. By way of example, Goodman cites the calcium-channel blockers, like Pfizer’s Norvasc, which treat high blood pressure and can cost more than $2 per pill. Last December, a study published in JAMA confirmed that those pills don’t work nearly as well as thiazide diuretics, or water pills, which cost just pennies per dose; yet the more expensive drugs, which are heavily marketed to doctors, are far more frequently prescribed.

To alert physicians to such troubling data, Goodman has begun setting up informational booths at medical conferences, prowling the hallways in a T-shirt sporting the No Free Lunch logo. He has also started “The Pledge,” an online oath that asks doctors to swear off pharmaceutical gifts; so far, more than 200 visitors to his site have signed the pledge.

Goodman’s next step is to convince med schools to educate their students about the ethical perils of accepting corporate gifts. Campus chapters of No Free Lunch regularly hold “pen exchange days” to get the message out, and Goodman works the lecture circuit. “But that’s going to do very little if med students look around and see their role models doing this,” he notes. “I’ll give a lecture to first-year students who that afternoon are going to spend their day with a [doctor] in the clinic. And those rounds will start with lunch with a drug rep.”