Indiana Rep. Mike Pence (center).Photo by Peter Marovich/Zuma

Like other super-PACs, RGA Right Direction PAC is authorized to spend unlimited money supporting or opposing federal candidates, so long as it doesn’t donate directly to them. So what is it doing giving $1 million to Rep. Mike Pence, Indiana’s Republican candidate for governor?

If Pence were running to keep his 6th District congressional seat, his campaign couldn’t accept a dime from Right Direction. Yet because he’s running for an office in a state that allows unlimited PAC contributions to candidates, the super-PAC can wire cash directly to his war chest.

Right Direction is funded entirely by the Republican Governors Association, a 527 organization dedicated to electing as many Republicans to governorships as possible—a mission fueled by contributions from some of the largest corporations in the country. In Indiana, candidates can accept unlimited donations from individuals and political action committees but only $5,000 from corporations and unions. Corporations and unions can also give to state PACs, but only in small sums.

The $1 million gift from Right Direction accounts for a third of Pence’s haul since April in his race to follow Gov. Mitch Daniels to the governor’s mansion. A week after getting the super-PAC infusion, Pence launched an early TV ad blitz. The first ad featured his wife recounting Pence’s homegrown Hoosier credentials.

Whether the check from the RGA super-PAC to Pence was drawn on a bank account that contained corporate money is not clear. In an email, RGA spokesman Michael Schrimpf said that “nothing in our reports suggests” that the organization gave corporate funds to Pence. All RGA expenditures, he said, come from a general fund. The Pence campaign did not return calls for comment.

But the gift, the largest one Pence has received, may be a way around state laws limiting corporate contributions to candidates. “In one way, it’s legal,” said Andrew Downs of the Center for Indiana Politics, at Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne. “But if you say this is a way to give in excess of corporate limits, that’s also absolutely true.” Bob Biersack, a senior fellow at the Center for Responsive Politics and former Federal Election Commission (FEC) staffer described it as “the new model of disclosure subterfuge. It’s not what a normal human being would call transparent.”

The donation to Pence appeared in FEC filings July 15. It is the latest in a series of campaign finance maneuvers by the RGA that have prompted legal challenges by two states that claim the group has violated limits on corporate giving.

In federal records, Right Direction reports its only donors as the RGA—which effectively obscures the original source of the $1 million check to Pence. The super-PAC reported receiving four contributions totaling $1.3 million from the RGA since January.

Right Direction’s 2010 boilerplate registration letter filed with the FEC said it “intends to make independent expenditures”—ad buys and other spending that supports or opposes candidates. FEC filings show the group has not reported any independent expenditures, but has spent money helping state candidates in Ohio in 2010 when it was known as RGA Ohio PAC. In addition to Right Direction’s $1 million contribution to Pence, it also made two contributions to the Montana Republican Party totaling $200,000.

The Right Direction PAC is registered with both Indiana and federal election regulators. But the state does not require any paperwork that might show whether its funds came from the RGA’s corporate donors. According to Abbey Taylor, a campaign finance analyst at the Indiana Election Division, “It’s a pretty nice little loophole, and loopholes are meant to be exploited.”

If a corporation wants to support a candidate for governor in Indiana, it can give only $5,000 to a PAC during each election cycle. PACs registered only inside Indiana must report those contributions to the state. For example, the Indiana Merit Construction PAC, gathered donations from dozens of construction companies and gave $32,500 to Mike Pence in June, bringing its total giving to the campaign to $69,000.

But Right Direction is not required to file such a report, according to state election officials. Because the Washington, DC-based Right Direction is registered with both the state and the federal government, the Indiana Election Division cannot regulate its spending activity. IED codirector Trent Deckard says state law limits his agency to regulating PACs that are solely registered with the state. “I truly understand the public concern here,” said Deckard, “but there’s 150 members of the legislature who would have to vote on this question. We can always hope for greater transparency.”

Corporations can also give directly to Indiana candidates, but no more than $5,000. Since January, Drug giant AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson have each given $2,500 and Nestle USA has given $5,000 to the Pence campaign. These same companies gave $350,000, $25,000, and $12,500 respectively, to the RGA’s parent 527 organization during the same time period.

The RGA’s Schrimpf says it is following the relevant state and federal campaign finance laws “as efficiently as possible.”

The RGA’s Schrimpf says it is following the relevant state and federal campaign finance laws “as efficiently as possible.”

The RGA has been a pervasive force in state elections. It has spent $80 million on state races in 40 states since 1999; its total election spending in 2010 was $131.8 million. More than half of that money has gone directly to candidates, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics. It gave seven-figure sums to six different gubernatorial candidates in 2010. The group was a top donor in the Pennsylvania, Illinois, Texas, Oregon, New Mexico, and Iowa races. In 2004 and 2008, its PAC also gave a total of nearly $3.9 million directly to Mitch Daniels’ successful bids for Indiana governor, according to the institute. “The RGA is confident they can get away with this—they’re riding on a new level of hubris,” said Edwin Bender, director of the institute.

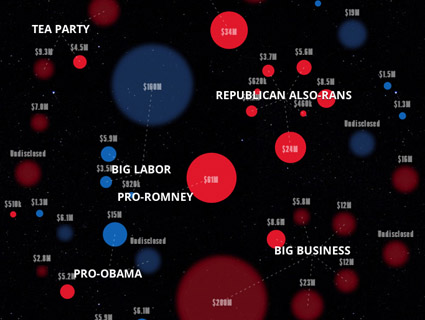

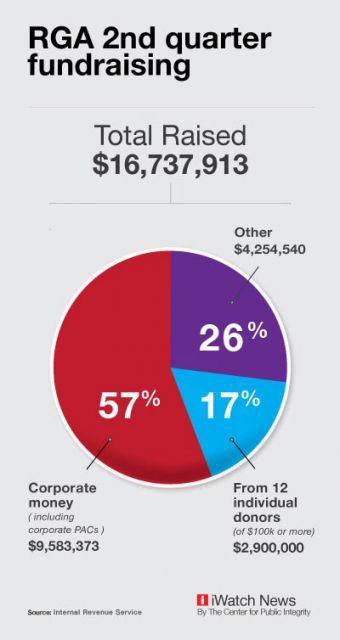

The RGA’s 527 has raised $16.7 million since April, nearly twice as much as its Democratic counterpart, the Democratic Governors Association (DGA). Fifty seven percent of that money came from corporate treasuries and corporate PACs, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of IRS records. Like super-PACs, 527s can accept unlimited contributions from corporations, unions, and individuals and may not give money directly to federal candidates. They are regulated by the Internal Revenue Service and are required to report their donors and spending.

In the 2012 election cycle, Koch Industries has given the RGA $2 million, health insurance giant Blue Cross/Blue Shield $1.6 million, and Sheldon Adelson’s Sands Casino group $1 million. The US Chamber of Commerce and Bob Perry have each added $750,000 to the RGA coffers, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

As of July 16, Pence had twice as much cash as his Democratic opponent John Gregg. The DGA has given Gregg $29,000 since January. The DGA’s June filing with the FEC reports that it has received money from small donors as well as $250,000 checks from each of the national teachers unions. Its Indiana PAC lists the DGA’s 527 as its only donor, raising similar questions about the origin of its contributions to Gregg. Officials at the DGA say its contributions are in compliance with state election law.

Following “the RGA’s million-dollar bailout,” Gregg spokesman Daniel Altman cited large donations from billionaire donors including the Koch brothers and Rick Santorum backer Foster Friess as evidence that Pence is “financed by out-of-state donors who do not have Indiana’s best interests at heart.” The $1 million contribution dwarfs one made by conservative industrialist David Koch, who gave $100,000 to Pence in January. Koch also gave $1 million to the RGA in February.

Indiana has not seen a seven-figure direct contribution to a candidate since 2003 when Bren Simon, the widow of an Indiana mall magnate, gave $1.3 million to former Democratic National Committee chairman Joe Andrew’s unsuccessful gubernatorial bid.

Some states have been concerned about the RGA’s influence. North Carolina and Vermont agencies have taken legal action against it, claiming it violated their states’ caps on corporate giving and must be regulated as a state PAC. In both cases, the RGA has used its pervasive reach as a defense, claiming that its “major purpose” is not to influence elections in any one state. Therefore, it has argued, no state can regulate it as a state PAC. “By that logic, they’re not a PAC anywhere, and can’t be regulated anywhere,” said Stetson Law professor Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, an election law expert. “Do we have political entities that are too big to regulate?”

In North Carolina, the RGA carried the day, despite spending way beyond the state’s limits for PACs. In Vermont, the RGA set up a state-affiliated PAC, but also bought ads through its 527 during the 2010 campaign—without reporting that spending to the state. Vermont’s Attorney General argued that this was a violation of campaign finance law, and the RGA has yet to present its defense. Vermont also claimed that a DGA-funded 527 called Green Mountain Future violated campaign finance law in 2010. The case is headed for the state’s Supreme Court.

“You need a state that’s willing to pick a fight with the RGA,” said Torres-Spelliscy, “but they’re so powerful that there’s this natural reticence to ticket them for running the red light.”

The Indiana Election Division usually does not take up its own investigations unless prompted by citizen complaints. So far, none have been lodged against the RGA’s activity. “Whether it passes the smell test is for voters to decide,” said Downs. “This is part of the shell game that concerns people about campaign finance.”

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit, independent investigative news outlet.