Image courtesy of Shutterstock

Got a tummy ache? It could well be something you ate. That’s the message from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest assessment of food-borne illnesses, dropped on its web site with zero fanfare, not even a press release, Friday afternoon. It shows that that infection rates from most common food-related pathogens are either inching up or holding steady—and occurring at levels above the CDC’s own targets.

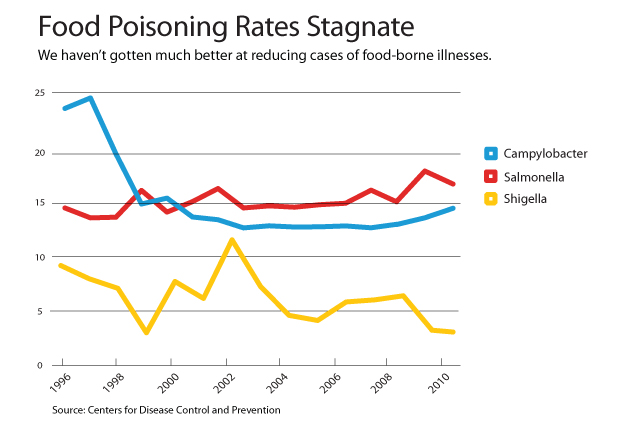

Here’s a look at how the rates three of the most common pathogens—campylobacter, salmonella, and shigella—have changed since 1996.

Chart by Azeen Ghorayshi

Chart by Azeen Ghorayshi

And for you disease wonks out there, here’s the data from the report, which includes numbers on some of the other common pathogens, as well. STEC refers to Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli strains—that is, the kinds that make you sick to your stomach—and the numbers are infections per 100,000 people.

Food poisoning: not getting better Source: CDC

Food poisoning: not getting better Source: CDC

The Consumer Federation of America, which publicized the CDC’s quiet release in a Friday post, is using the occasion to hector the Obama administration to move forward with the implementation of the food-safety overhaul, which he signed into law way back in January 2011. True, the administration has been egregiously slow in putting the law into effect, but it would have a limited effect on most of these diseases. Why? Because it has no bearing whatsoever on meat production, the main source of these pathogens. (Shigella infections, which are happily falling, have nothing to do with meat production—they come from food contaminated by “infected food handlers who forget to wash their hands with soap after using the bathroom,” the CDC reported.) The Food Safety Act overhauls only the nonmeat part of the food system, overseen by the Food and Drug Administration. It leaves the meat side, handled by the US Department of Agriculture, unreformed.

And as the Consumer Federation of America itself puts it, “Salmonella and Campylobacter illnesses are frequently associated with consumption of raw or undercooked poultry.”

Poultry production falls under the oversight of the US Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service—and amazingly, the USDA has proposed new rules that would essentially eliminate its own inspectors from poultry plants, leaving inspection to the industry itself, while also allowing for a dramatically speeded-up kill line. The Consumer Federation of America is not impressed with the plan:

[T]he Food Safety and Inspection Service has proposed a new inspection program for poultry, yet the agency has almost no data on how the program will actually affect Campylobacter rates on poultry. The agency’s proposal also does not require poultry plants to test for Salmonella and Campylobacter, significantly limiting the agency’s ability to assure that poultry plants are reducing contamination from these pathogens.

And then there’s the whole problem of antibiotic resistance, which the CDC report doesn’t touch on. Eighty percent of US antibiotic use occurs on livestock farms, the vast bulk of it on factory-scale animal farms, and the FDA has acknowledged that daily small doses of the drugs gives rise to meat laced with antibiotic-resistant pathogens.*

Note from the above chart that infection rates of the most famous pathogen of all, the extremely virulent E. coli (STEC) 0157, have fallen dramatically over the past decade and a half. That’s mainly because, after a deadly outbreak at Jack in the Box in 1993, the USDA cracked down on the beef industry, declaring the 0157 bug an adulterant. The agency did the same with six non-0157 E. coli (represented in the above chart as STEC 0157) strains this year—and it was about time, too, because rates of infection from these six non-0157 E. colis have risen dramatically since 2000. But other pathogens, including salmonella and campylobacter, aren’t considered adulterants and routinely show up on retail meat.

We know from the the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System, a collaboration of the Food and Drug Administration, the CDC, and the USDA, that the meat sold at supermarkets and other retail outlets is routinely riddled with pathogens resistant to one or more antibiotics. Here’s the latest report, which documents rising levels of antibiotic-resistant strains of salmonella. campylobacter, and non-0157 E. coli on common meat cuts.

Then there’s the problem of antibiotic-resistant pathogens that aren’t officially counted as food-borne, but which may well be infecting people through food. The most famous is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, better known as MRSA. This often deadly pathogen first appeared in hospitals, but it has been increasingly showing up in people who have had no recent contact with medical facilities. As The Atlantic‘s Brian Fung recently reported, MRSA infection rates have doubled over the past five years—and most of that increase is accounted for by infections that took place outside of hospitals. A likely vehicle for MRSA transmission is through pork—it’s rampant on large-scale hog farms and has been found on retail pork chops. Another example is a form of E. coli that doesn’t cause gastrointestinal trouble but appears to be causing antibiotic-resistant urinary-tract conditions in women, as the excellent reporter Maryn McKenna showed recently. Its likely source: chicken.

But after 30 years of foot dragging on regulation of antibiotic use on factory farms, the FDA finally proposed a new plan to deal with it in April—but, alas, the proposed new rules would be voluntary, and they contain a gaping loophole to boot.

While federal regulators play Keystone Cops with food safety, some serious public health issues are festering. For one thing, catching a bug from an undercooked chicken breast or a cross-contaminated cutting board can mean more than a bad tummy ache—even if doctors can get hold of an antibiotic that’s actually able to treat it. As McKenna reported in a recent issue of Scientific American, new research is linking common bouts of salmonella and campylobacter poisoning with long-term health disorders ranging from arthritis to Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare autoimmune disorder. McKenna writes:

As researchers look back at foodborne outbreaks, they are not only confirming that these complications appear in survivors but adding to the list of illnesses that may occur. A survey of 101,855 residents of Sweden who were made sick by food between 1997 and 2004 found, for instance, that they had higher-than-normal rates of aortic aneurysms, ulcerative colitis and reactive arthritis. A review of a major provincial health database in Australia revealed that people there who contracted any bacterial gastrointestinal infection were 57 percent more likely to develop either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, another chronic bowel condition, than people born in the same place and era who had not had such infections. And several years after a 2005 outbreak of Salmonella in Spain, 65 percent of 248 victims said they had developed joint or muscle pain or stiffness, compared with 24 percent of a control group who were not affected by the outbreak.

The CDC report reminds us that our food-safety situation isn’t getting any better. And the consequences may be worse than even critics like me currently think.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that 80 percent of US antibiotic use occurs on factory farms. The sentence has since been fixed.