Will Seberger/ZUMAPress.com

Naming its long-awaited comprehensive immigration bill the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013 wasn’t just an alphabetical flourish by the bipartisan Senate Gang of Eight: Securing the border always was going to be its No. 1 stated goal.

So it’s no surprise that the bill calls for the Department of Homeland Security to present Congress with plans for security and fencing strategies for the southern border before any of the country’s 11 million undocumented immigrants can become “Registered Provisional Immigrants,” allowing them to legally live and work in the United States. And before RPIs can apply for green cards, a border enforcement plan must be “substantially operational,” “maintaining effective control in all high-risk border sectors” in the Southwest.

Too bad, though, that there’s still no way to know how the bill’s benchmark border security stats will be determined.

According to the bill outline, the two key metrics in high-risk border sectors are:

1) Persistent surveillance in High Risk Sectors along the Southern Border; and

2) An Effectiveness Rate of 90% in a fiscal year for all High Risk Sectors along the Southern Border

Definitions are important here. The Senate outline defines high-risk border sectors as those “where apprehensions are above 30,000 individuals per year”; in fiscal 2012, that included three of nine southern border sectors (PDF): Tucson (120,000 apprehensions), Rio Grande Valley (97,762), and Laredo (44,872).

“Persistent surveillance” is a little trickier. Does it imply merely detecting illegal activity, perhaps with the drones that will be paid for with the $3 billion allotted for the southern-border security strategy? Or does it mean something akin to what the Border Patrol has called operational control, in which the agency has “the capability to detect, respond to, and interdict cross-border illegal activity”? As this chart from a February GAO report (PDF) shows, the Border Patrol’s operational control over the southern border at the end of fiscal 2010 varies quite a bit from sector to sector, with 44 percent of the 2,000-mile border covered:

The Border Patrol switched in fiscal 2011 from operational control to apprehension totals as a stop-gap security metric. The plan had been for Homeland Security to develop a holistic measure called the border condition index, but as Secretary Janet Napolitano admitted at a March roundtable with reporters, the BCI still doesn’t exist. (After Napolitano warned against relying on one security statistic as a sort of border Holy Grail, Rep. Candice Miller (R-Mich.) responded, “I don’t think we’re searching for the Holy Grail, as they say. It is not rocket scientry.”)

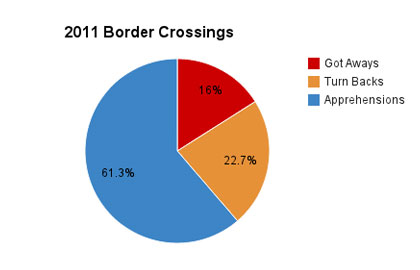

That’s where the Border Patrol’s effectiveness rate comes in: The bill outline defines it as apprehensions plus “turn backs” divided by the total number of illegal entries. Therefore, in high-risk sectors, the Border Patrol must catch at least 90 percent of border-crossers. While the Border Patrol doesn’t share its data on attempted crossings on its site, another GAO report (PDF) from December 2012 did, showing an 84 percent effectiveness rate along the entire southern border in 2011.

As far as the highest-risk sectors went, Tucson (86.9 percent) and Laredo (84 percent) finished right around average, while Rio Grande (70.8 percent) had the second highest percentage of got aways after Big Bend (68 percent) in 2011.

The thing is, those numbers are flawed. According to that December 2012 GAO report, differences in how individual Border Patrol sectors define, collect, and report data on turn backs and got aways have kept the agency from comparing results across regions. And as the New York Times‘ Damien Cave pointed out last month, the data includes “only the immigrants they detect, not the countless others who cross without anyone noticing.”

So what happens if the Border Patrol doesn’t meet its border security goals? If it doesn’t report a 90 percent effectiveness rate in high-risk sectors within five years, then a commission made up of border governors and other appointees will form to make suggestions. As my colleague Adam Serwer has pointed out, that type of commission is, well, problematic.

“We are going to get the toughest enforcement measures in the history of this country,” said Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) during his tour of Sunday’s morning political shows. “We are going to secure the border to the extent that’s possible.”

Whether that’s enough to get a bill passed remains to be seen.