Shutterstock

A chemical common in food packaging—Bisphenol-A (BPA)—has for years been scrutinized for potential links to reproductive problems, heart disease, cancer, and even anxiety. And now new research suggests BPA, which leeches out from things like aluminum cans, drink straws, plastic packaging, and even cashier’s receipts, could increase the risk for obesity in preteen girls.

A Kaiser Permanente study, published this week in PLOS ONE, examined obesity and BPA levels in a group of Chinese school children. While most of the kids were not significantly effected by the chemical, 9-12 year-old girls with high BPA levels in their urine were found to be twice as likely to be obese than other girls their age. In girls with especially high levels (more than 10 micrograms per liter) the risk of obesity was five times as great.

This isn’t the first study to reveal BPA’s particular effect on girls. My colleague Jaeah Lee explored how girls exposed to the chemical as fetuses were more likely to be anxious and depressed than boys, and another study on rhesus monkeys revealed how it messes with the reproductive system. So why are women more susceptible to the chemical?

The new Kaiser study suggests that, long after fetal development, girls in the throes of puberty may be particularly sensitive to BPA. Though his research didn’t focus on why exactly BPA might impact pubescent girls, Dr. De-Kun Li, the study’s principal investigator, offered some clues. BPA, considered an endocrine disrupter, mimics the hormone estrogen. Estrogen doesn’t just impact reproductive functions, says Li, a reproductive and perinatal epidemiologist. It also shapes the metabolic process: how the body absorbs, metabolizes, and stores energy. “Puberty is the process of accelerated growth, what we commonly call a growth spurt,” he explained. In puberty, girls’ bodies produce more estrogen, triggering all kinds of transformations that rely on heightened metabolism. Add higher levels of BPA, and the body’s delicate chemical balance could become disrupted. “For whatever reason—we still don’t have all this worked out—you screw up your normal process, resulting in over-storage or over-absorption [of fat], or it reduces metabolism.”

And there’s more evidence supporting the theory that girls could be especially vulnerable to BPA: A large international study of twins last year revealed that environmental factors have a greater impact on girls’ weight than on boys’, which is more swayed by genetics.

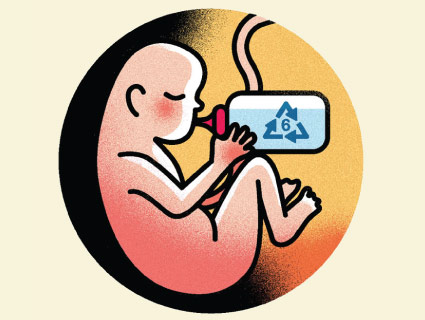

Li’s study adds to a growing body of research that sheds a darker light on this chemical, such as a 2012 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association that also found links between high BPA levels and obesity in kids and adolescents. The FDA remains skeptical that low levels of BPA cause any harm, and the food industry continues to happily put it in all sorts of packaging, like the can linings of Coca-Cola products. In a move meant to assuage parental concerns as much as to address safety, the FDA banned BPA from baby bottles and sippy cups in 2012. The agency also claims to be “supporting efforts to replace BPA or minimize BPA levels in other food can linings.”

Li, who in the past has published studies on BPA’s association with low birth weight, decreased sperm count, and higher risk of sexual dysfunction, indicated that research on women may eventually prove the chemical’s risk to humans and its role in the obesity crisis. His next field of study? “In utero exposure, that’s the key. When you’re born, your development is already damaged. People are just starting to realize that that’s the problem.”