Can a state ban a type of abortion, entirely? That’s the question the US Supreme Court is now weighing.

In June, the court agreed to hear a challenge to a 2011 Oklahoma law that bars doctors from prescribing abortion drugs, unless they follow the FDA label. Supporters of the bill argue the goal is to protect women’s health. “Oklahoma has acted to regulate a dangerous off-label use of a drug regimen that is tied to the deaths of at least eight women,” says Mailee Smith, a lawyer for Americans United for Life, which drafted the legislation. But critics maintain the language is so broad it would block access to all abortion drugs—including those used to treat life-threatening ectopic pregnancies. And the Oklahoma Supreme Court agrees. In response to a query from the US Supreme Court, on Tuesday the state court ruled that the bill effectively “bans all medication abortions” and thus is unconstitutional.

It may seem counterintuitive that following the FDA labeling would hamper access. But two of the three most commonly used abortion drugs, misoprostol and methotrexate, were initially approved to treat other conditions. The World Health Organization and independent researchers have since found that they are a safe and effective way to end an early pregnancy, and doctors routinely prescribe them for this purpose. But the drugs’ manufacturers never went through the costly process of updating their FDA labels. This is not unusual. Once a drug is approved, the FDA normally doesn’t change the label unless new risks come to light. But doctors are free to tailor treatments to reflect the latest research, which is one reason that roughly 20 percent of all outpatient prescriptions are off label.

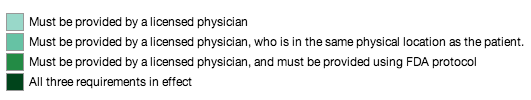

A state-by-state LOOK AT abortion drug restrictions

Hover over a state to see a breakdown of restrictions in place there. Source: Guttmacher Institute.

?

Women’s health advocates are particularly alarmed by the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s finding that the law would ban the use of methotrexate to treat ectopic pregnancies (when an embryo develops outside of the womb). The only other treatment for this condition is surgery. According to Nancy Stanwood, the chairwoman of Physicians for Reproductive Health and chief of family planning at the Yale School of Medicine, this isn’t a safe option for every patient. “Some women may not be candidates for surgery because they have underlying medical conditions or a high-risk of complications from anesthesia,” she explains. “Taking methotrexate off the table would be devastating.”

The Oklahoma Supreme Court also found the measure would bar the use of the lone FDA-labeled abortion drug, RU486 (also known as Mifeprex or mifepristone). Why? Because RU486’s label calls for taking it in combination with another pill that’s not FDA-approved for abortion—meaning it’s impossible to prescribe the two drugs in a way that complies with both of their FDA labels.

Shortly after the Oklahoma Legislature passed the abortion-drug law in 2011, the Coalition for Reproductive Justice and the Center for Reproductive Rights sued to block it—and won. In his opinion, District Judge Donald Worthington concluded that the law was “so completely at odds with the standard that governs the practice of medicine that it can serve no purpose other than to prevent women from obtaining abortions.” The Oklahoma Supreme Court later upheld the decision, but it didn’t spell out its rationale.

After it agreed to take the case, the US Supreme Court asked the Oklahoma Supreme Court to clarify the breadth of the law and whether it barred all abortion drugs, which is how Tuesday’s ruling came about. Some court watchers suspect the Oklahoma court’s finding will be enough to persuade the US Supreme Court justices to drop the case. “They may well dismiss the case as improvidently granted, meaning they say, ‘Never mind, we’re not going to weigh in,'” explains Hank Greely, who directs the Center for Law and Biosciences at Stanford University. If that happens, the law would remain blocked.

The Oklahoma measure is part of a wave of restrictions on abortion drugs sweeping through the United States. According to the Guttmacher Institute, in recent years at least 39 states have passed bills clamping down on abortion drugs by, among other things, requiring doctors to be physically present when patient takes the drug.

On Monday, a federal court in Texas upheld the part of the state’s ultra-strict abortion law requiring women to use RU486 according to the FDA label. While less restrictive than the Oklahoma bill, critics argue the Texas measure—and similar ones on the books in three other states—seriously intrude on the doctor-patient relationship.

Under these laws, doctors would be required to use the exact RU486 regimen called for in its FDA label, which was approved 13 years ago. Since then, studies by the World Health Organization and independent scientists have found that the drug is equally effective at a third of the original dose. What’s more, the drug can be used nine weeks into pregnancy, rather than just seven, as its label states. Both the WHO and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommend a lower dose and fewer doctors’ visits than outlined by the FDA. In its Monday ruling, the Texas court explained why the FDA-recommended approach has fallen out of favor:

[T]he FDA protocol is assuredly more imposing and unpleasant for the woman, requiring at least one additional visit to a clinic and allowing less control over the timing and convenience of the medically induced miscarriage. It also requires more of the physician’s time, as the physician must administer the second dose. The FDA protocol is also marginally more expensive, due to the increased dosage, notwithstanding any additional cost of travel, time off of work, and childcare. Most importantly, the FDA protocol removes medication abortion as an option for any woman who discovers she is pregnant or decides to terminate a pregnancy after [7 weeks].

Still, the court found the law was constitutional, except in cases where a woman’s life was endangered by lack of access to abortion medications.

When the FDA approved RU486 in 2000, some predicted it would lead to a surge in abortions and make it more difficult for opponents to fight—no more picketing abortion clinics. In fact, the overall number of abortions has dropped, and a greater share of women are getting abortions in the first weeks of pregnancy, thanks partly to abortion drugs, which can be used earlier than other readily available abortion methods. (One in five early abortions in the United States today are performed with medication.)

Abortion drugs can make it easier for rural women, in particular, to access early abortions. As New York magazine has reported, in 2008, Planned Parenthood of the Heartland launched a program to improve access in far-flung parts of Iowa by allowing doctors to prescribe abortion drugs remotely. Women could walk into any of the state’s 17 clinics, get an ultrasound, and consult with a doctor at one of Planned Parenthood’s larger, urban offices using internet video conferencing, after which the doctor would push a button and dispense the first dose.

But that model is slowly disappearing. Seventeen states—including Iowa—have laws on the books requiring the doctors who prescribe abortion drugs to be physically present. Like the Texas law requiring abortions to be performed in a particular kind of surgical center, the abortion-drug measures are ostensibly meant to protect women’s health. But in practice they block access. If the US Supreme Court moves ahead with the Oklahoma case, Greely of Stanford says it could be a litmus test for this strategy of restricting abortion through piecemeal legislation based on dubious concerns. “Any Supreme Court decision upholding one of these measures,” he says, “makes all the others that much more viable.”