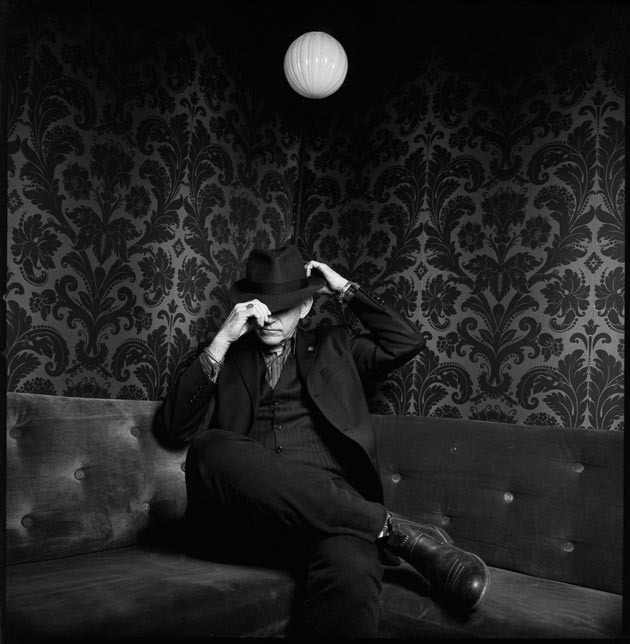

Benmont Tench III has helped create the musical fabric of hundreds of records, both as a founding member and piano/organ player of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and a session musician on recordings for the likes of Bob Dylan, Johnny and Roseanne Cash, Willie Nelson, Roy Orbison, John Prine, and Ryan Adams. Tench is the true musical insider, not just in the company he keeps, but also in his willingness to support the artistic visions of the legends he works with.

Forty years into his career, Tench recently released his solo debut, You Should Be So Lucky, on Blue Note Records. Consisting mainly of original songs, the album was produced by Glyn Johns (The Stones, Led Zeppelin, The Who, Eagles, etc, etc). Jacob Blickenstaff photographed and spoke with Benmont at Rockwood Music Hall in New York City, the following is in his words.

I had periods of downtime between tours. I never liked taking sessions just to make money and I didn’t have to because I had the Heartbreakers. It was more to learn something. What you learn, you bring to the next session, you bring that back to the band. I’ve come to believe that you shouldn’t take the session unless you like the people and the music, because you won’t be able to give it your all—and that’s your job, to give it your all.

What a good session musician does is listen, to the song, to the artist, and to the other players. That way you can help bring out the song and help the artist express what they want to express. It’s never about you stepping out and showing you can play something fancy. It struck me very early on, the simple way to do it, which I learned from listening to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, records on Stax and Atlantic. There’s so much power to something like “Louie, Louie.”

Listen to the Beatles’ “Things We Said Today.” Ringo Starr does not play a fill in the entire song. It doesn’t need it. “A Day In the Life” has gorgeous fills, but there the song needs it. When I play on any record, I’m striving to get where Ringo is. You play what doesn’t take you out of the song. It’s not a bad philosophy of life, if I could just learn to stick with it.

Glyn Johns had offered to do an album with me a long time ago. Part of me was like, “He can’t possibly mean it, he’s just being nice.” But when I came to believe in the songs, I took him up on it. I can say a bit facetiously: You make a record with Glyn Johns because how can you not? He really knew how to lead me in a certain way without telling me what to do. That’s a gift. And he’s a great hang.

It took me a long time to do a record because I wasn’t sure if the songs were good enough. I’ve spent most of my life playing with Tom Petty, and he’s a damn good songwriter. It’s a very high standard to hold yourself to. But I got encouragement from a lot of people. It wasn’t that I should get a hearing; it was that the songs should get hearing. I felt like they showed up for a reason, some of them were very fresh when we recorded them, a couple songs date back about 30 years. Some things that you are scared of are healthy things to do.

“Contact” is an occasional series of portraits and interviews by Jacob Blickenstaff.