September is upon us, and American kids are filling up their backpacks. But lots of kids won’t be going back to school—at least not very much. The map above shows the results of a national report released Tuesday by nonprofit Attendance Works, which zooms in on a statistic called “chronic absenteeism,” generally defined as the number of kids who miss at least 10 percent of school days over the course of a year. The measure has become popular among education reformers over the past few years because unlike other measures like average daily attendance or truancy, chronic absenteeism focuses on the specific kids who are regularly missing instructional time, regardless of the reason why or the overall performance of the school.

Several studies have shown that missing 10 percent of school seems to be a threshold of sorts: If you miss more than that, your odds of scoring well on tests, graduating high school, and attending college are significantly lower. A statewide study in Utah, for example, found that kids who were chronically absent for a year between 8th and 12th grades were more than seven times more likely to drop out. The pattern starts early in the year: A 2013 Baltimore study found that half of the students who missed two to four days of school in September went on to be chronically absent.

The Attendance Works study, which used missing three days per month as a proxy for the 10 percent threshold, categorized students missing school by location, race, and socioeconomic status. Here’s what they found:

Oddly enough, the federal government doesn’t track absenteeism. Seventeen states do, and, as David Cardinali wrote in the New York Times last week, states have found that school attendance often falls on socioeconomic lines: In Maryland, nearly a third of high school students who receive free or reduced lunch are chronically absent.

In order to work with a national dataset, Attendance Works looked at the results of the National Assessment for Educational Attainment, the nation’s largest continuing standardized test, taken by a sample of fourth- and eighth-graders across the country every two years. In addition to academic content, the test asks students a series of nonacademic questions, including how many days of school they have missed in the past month. If students reported missing three or more days, they had crossed the 10 percent threshold; assuming that month is representative of the rest of the year, the kids qualify as chronically absent.

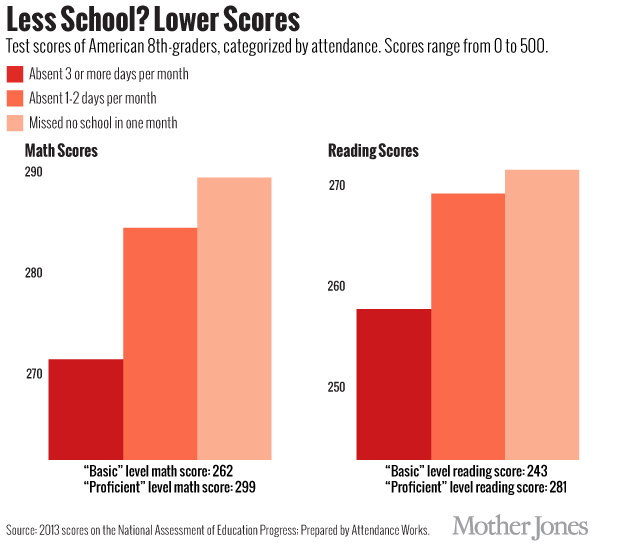

Obviously, there’s a huge disclaimer here: Students may not remember or accurately report their own absences, and one month may not be representative of an entire school year. But at the same time, the results were remarkably consistent, reflecting conclusions from localized studies: Students in poverty are less likely to come to school, and as the chart below shows, students who come to school less perform markedly worse on tests. (For reference, an improvement of 10 points on the National Assessment for Educational Progress is roughly equivalent to jumping a grade level.)

Phyllis Jordan, a coauthor of the Attendance Works report, hopes that as schools look more into the data, they’ll be able to identify the core reasons for the absence: “If everybody from a certain neighborhood is missing school and they have to walk through a bad neighborhood, then suddenly you say, ‘Oh, we should run a school bus through there.’ If it’s all the kids with asthma and you don’t have a school nurse, maybe that’s a reason. Or maybe it’s all concentrated in a single classroom, and you have an issue with the teacher.”

The good news is that citywide studies in New York City and Chicago show that when chronically absent kids start coming to school more, they can make substantial academic gains. And the simple act of tracking and prioritizing absenteeism can lead to statewide progress: When Hawaii started keeping track of chronic absenteeism in 2012, the state went from having a chronic absentee rate of 18 to 11 percent over the course of a single year.