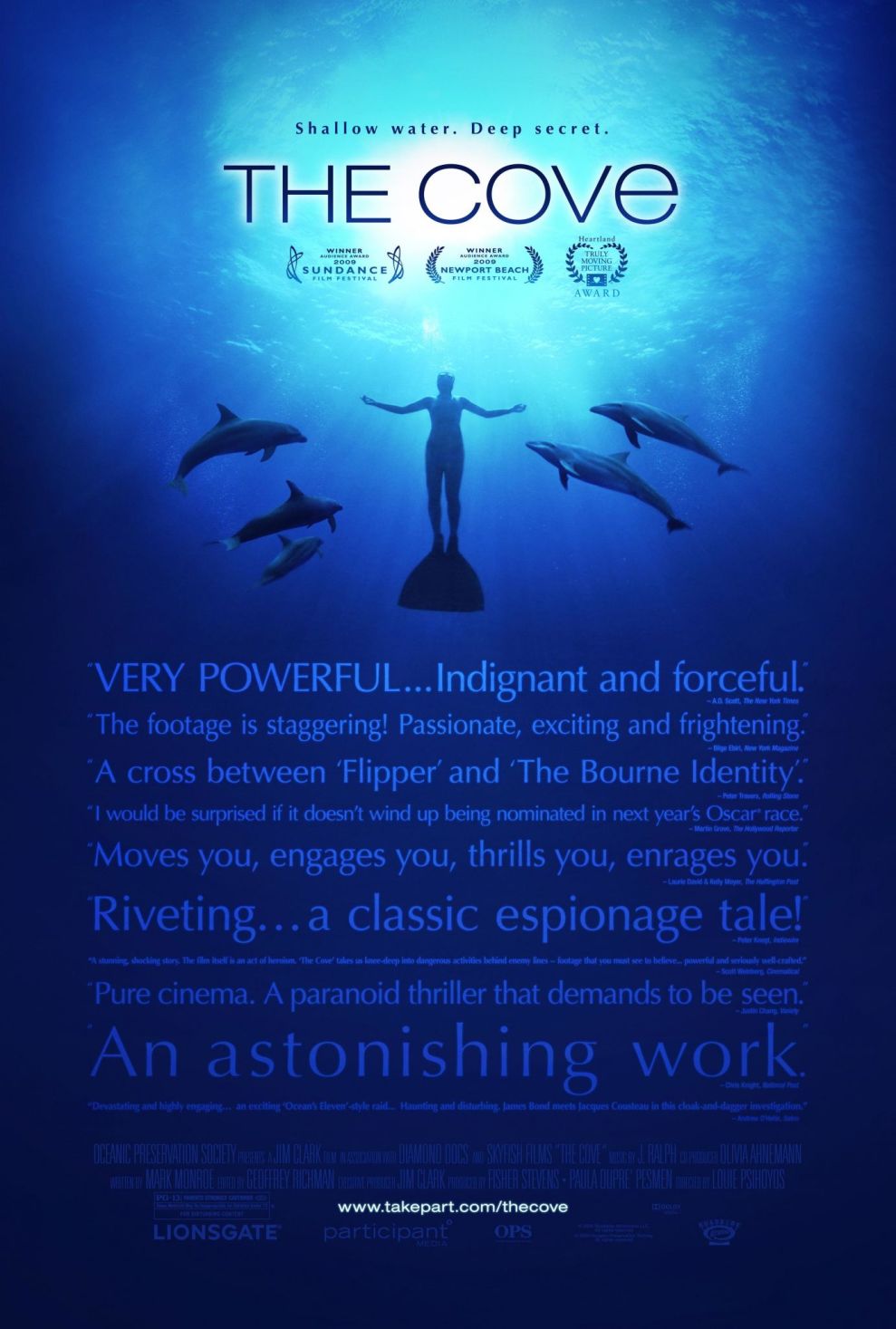

There’s something fishy about the coastal town of Taiji, Japan: Statues and murals of dolphins line the streets, yet every year, the town’s fishermen kill thousands of dolphins and sell their meat. That’s a whole lot of dead dolphins—you’d think some enterprising activist journalist would have blown Taiji’s cover long ago. They tried, but no one could penetrate the heavily guarded cove where the killing takes place. Until now. When photographer Louie Psihoyos heard about Taiji, he teamed up with marine mammal activist (and former Flipper TV dolphin trainer) Ric O’Barry. Together, the two launched a high-tech espionage mission to infiltrate the cove and expose the slaughter. We spoke with O’Barry and Psihoyos about making The Cove, assembling an Ocean’s Eleven-style team, and why a little paranoia can be a good thing.

Mother Jones: Louie, you’re a photographer by training. How did you get involved with making a documentary?

Louie Psihoyos: Jim Clark—the guy who financed the movie—he and I have been dive buddies for years. He’s a serial entrepreneur—he started Netscape. We’d been diving around the world and watching the degradation of the oceans. During a trip to the Galápagos in October 2005, Jim said, We should do something about this. So he had the idea of starting the Oceanic Preservation Society. Two months later I met Ric at a marine mammals conference. He was banned from talking. I called him, and he started telling me about the dolphin slaughter in Taiji. He said, “I’m going next week. Want to come?” I took a three-day crash course on how to make a film. And I went to Taiji.

MJ: What were your first impressions of Taiji?

LP: It was like walking into a Stephen King novel. Everywhere you go there are statues of whales and dolphins. There are signs that say, “We love dolphins.” But in the center of town is this horror show. Right between the whaling museum and City Hall. It’s in a national park! If you were to write this as a novel, people would say it was too over the top. My journalistic instincts turned on. I thought, this is a great story. But here’s the problem: All the dirty business happens in this secret cove, but you can’t see it. People have been coming for decades to try to document it. At that point, I realized I was no longer just a journalist covering a story. By trying to get into the cove, I was becoming an activist.

MJ: Louie, in the film, you say you were feeling like you had gone halfway around the world to end up in a car with this paranoid guy (meaning O’Barry). Ric, how did you convince Louie that you weren’t just some wacko?

Ric O’Barry: [Laughs.] Well I never did!

LP: First of all, the cops were behind us. The paranoia was well founded.

RO: If you’re a Westerner and you’re in Taiji and you’re not paranoid, you’re not paying attention. It really is dangerous there. The police aren’t our enemy. Neither are the fishermen, though they are very angry, and there’s always a chance one of them will get drunk and do something stupid. But the real danger is the Yakuza, the Japanese mafia. They’re always lurking around. Some of the fishermen are connected. The Yakuza is very involved in the fishing and whaling industry, so they know what’s going on. They normally don’t bother with Westerners, but this is a special situation. So being on high alert all the time is the safe thing to do.

MJ: The Yakuza didn’t really make it into the movie. Why not?

LP: They were following us around for a bit. After a while we had identified the cars, determined who was in which car. The Yakuza really stood out in that community. Slicked-back hair, wraparound glasses; they looked like they came out of central casting. A Japanese version of The Sopranos. But the police were the ones that were following us around 24-7. We had five hotel rooms; the police had five hotel rooms. We would go out; they would go out. Even in the middle of the night, they’d follow us. They would stay four or five blocks behind. We would set up decoys to throw them off. We had a car that was rented by a Japanese assistant, in his name. We’d park it outside of town; we’d go around a corner and all hop out of the van and hide behind it. The police would follow this other car, and we’d just take them on a wild goose chase for a few hours outside of town while some members of our team were at the cove.

MJ: But in the movie, you never have a real run-in with the police.

LP: But we did have run-ins. They were really curious about what we were doing late at night. After a few weeks of that the chief of police asked us what we were doing. I said, “We’re looking for a place to live.” He said, “What are you here for?” I said, “That’s kind of a rude question to ask of a foreigner. Why do you want to know?” He said, “I need to get some sleep.” The 24-hour surveillance was really cramping his style. We got run out of the prefecture once. The chief of police said, “You have to go right now or I’m going to arrest you.” He was obviously under a lot of pressure to find out what we were doing there. He couldn’t figure it out. Two months later I was back again.

MJ: They couldn’t figure out why you were there? They must have known it had something to do with the dolphin slaughter.

LP: A lot of times, our high-tech cameras, hidden in rocks, were rolling while we were back at the hotel. So they couldn’t figure it out. We tried never to be seen at the cove.

MJ: What was the hardest part of the whole operation?

LP: Just getting it all together was the hardest part. There were so many moving parts. It was like an Ocean’s Eleven team. We had 60 cases of high-tech surveillance gear that we had to get through customs, and a lot of this stuff wasn’t off the shelf; we actually had to make it. And we had to bring all these people together. The joke of the movie was that we’re all professionals, just not at this. We had a world champion free diver who could go down to 300 feet, and now she’s setting up microphones and underwater cameras for us. Implementing it was hard, too. A lot of it was done in the middle of the night: You’re awake, you’re afraid, you’ve been up for days getting all this gear together, and now it’s go time. You know the cops are out there. If the cops had searched our car that probably would have been enough to put us in jail for several months. We had runners whose only job was to get the footage off the camera, back it up, then get it out of the country. We didn’t want to be caught with more than one day’s footage. It’s a lot of stress. I stopped drinking for fourteen months. It would have been too easy to have a glass of wine at the hotel every night. But I wanted to be completely aware of what was going on.

MJ: Were there scenes that got edited that you wish had stayed in?

LP: There was one scene I fought for so hard: We had this rock camera in front of a campfire scene. These fishermen were sitting around on the beach and talking about how you used to be able to kill the large whales, just like the dolphins. These guys are responsible for killing blue whales, which still haven’t recovered from the ’70s. Now they’re about to do the same thing with dolphins. Another great scene that didn’t make the cut: One of those same fishermen said, “I was trying to watch TV last night but I couldn’t hear it. I turned up the sound all the way. My wife and son said, ‘Why do you even bother watching TV? You can’t hear it anyway.'” We’re thinking, he has mercury poisoning.

MJ: What do you think are the chances that once this film is released in Japan, dolphin slaughter will end?

RO: I think that’s going to happen. If the film does well, that kind of external pressure will be hard for the Japanese government to deal with.

MJ: Have you had any reaction from the Japanese government to the film?

LP: Last year I was going down to Santiago, Chile. Sitting next to me on the plane was the head of the Japanese fisheries. I showed him a preview of the movie. So he had the information, but a year has gone by and he hasn’t done anything about it. So it seems like he is complicit.

MJ: The fishermen at the cove say that killing dolphins is the Japanese way of life, something they’ve been doing for generations. Is there any cultural or economic legitimacy to that claim?

RO: How can it be the culture if the Japanese people don’t even know about it? We interviewed a hundred people on the streets of Kyoto. They simply don’t know. The reason they don’t know is that there’s a media blackout on all whale and dolphin stories. But for a moment, let’s assume they’re right and I’m wrong, that it is their culture. It doesn’t mean it’s okay.

LP: And it’s not just an animal rights issue. These animals are so toxic that it becomes a health issue. Their mercury levels are through the roof. Some of the meat tested had 5,000 times more mercury than is allowed by Japanese law. One of the great ironies of this movie is that dolphins are one of the only animals that will come to the aid of human beings. What’s going to save the dolphins is that humans have made them toxic. That’s the one thing that’s going to save them from being eaten.

Read the Mother Jones review of The Cove here.