<a href="https://interstellar.withgoogle.com/transmissions#/gallery">Paramount Pictures and Warner Bros. Pictures</a>

In the new sci-fi epic Interstellar, Matthew McConaughey and Anne Hathaway don astronaut suits, leave an Earth that has been so poisoned it can no longer produce food to support the human race, and zip through a wormhole in search of new planets where homo sapiens might be able start over—while Jessica Chastain works on a mathematical formula that will allow our species to defy gravity. The big-budget blockbuster is a familiar gotta-save-humanity cinematic romp, chock-full of dramatic chills and special effects thrills. But Interstellar, directed by Batman movie-maker Chris Nolan, also attempts to attain a certain gravitas by taking seriously the science invoked within the film. After all, Kip Thorne, one of the world’s leading theoretical physicists and experts on relativity, was an executive producer and consultant for the movie. And Neil DeGrasse Tyson has praised the flick for featuring scientific principles “as no other feature film has shown.” But one of our planet’s top astrobiologists has a somewhat different view.

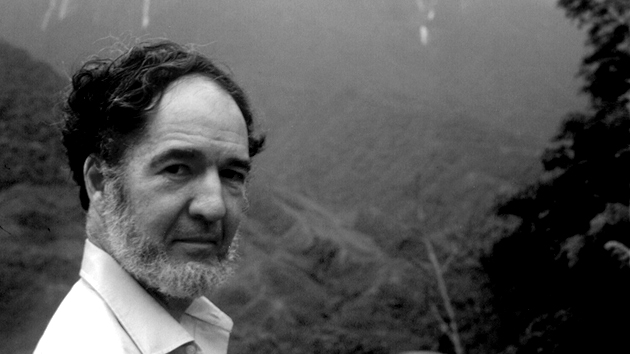

I took David Grinspoon, who holds the chair of astrobiology at the Library of Congress, to the Washington, DC, premiere of Interstellar—a posh event held at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum and attended by pundits, scientists, and aerospace firm officials and lobbyists. Afterward, he and I recorded an episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast focused on the science and themes of this grand film.

Grinspoon, a 2006 winner of the Carl Sagan Medal, advises NASA on planetary exploration and is involved with the Venus Express spacecraft and the Curiosity Rover on Mars. He is a widely-recognized expert on the possibility of life beyond Earth. He runs a funky website and is working on a book about the anthropocene—the somewhat controversial notion that the Earth is in a geologic epoch being shaped by human activity. And a few years ago, he attended a meeting of scientists called together by the makers of Interstellar—back when Steven Spielberg was slated to direct the film—to kick around the scientific ideas presented in the movie. That is, Grinspoon was the perfect date for this movie.

So, I asked him, what was it like to be present at creation? Grinspoon recalled:

There was a meeting of the minds that a bunch of us were invited to…on the Caltech campus. It was really fun. They had some astronomers, astrobiologists, psychologists…They presented the very basic premise of the film and asked us to brainstorm on some of the themes, and they recorded the whole thing. Spielberg showed up, and he brought his dad…It was a very wide-ranging discussion…What I remember of the treatment that we saw at that time…it had some of the same themes of getting to other planets and using black holes. But that was kind of it. It didn’t have the plot yet…If memory serves me, the original story actually had [theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen] Hawking as a character in the film, who was going to be sent into orbit. Experiencing weightlessness is something that helped him with his disability…I don’t know how much of this I’m conflating now. It’s been a few years. But I think there was even a love interest.

Stephen Hawking playing Stephen Hawking in love in outer space? “Exactly,” Grinspoon said. “Those themes of love and space are still in the final movie”—even though Hawking isn’t.

But back to the science: Do wormholes, which defy conventional physics and our down-to-earth notion of time, exist? Can they be stellar shortcuts used to get from one end of the universe to the other in a flash? And can they be created by sentient beings, as the movie suggests? Well, maybe, Grinspoon said, but there’s at least one big problem with using a wormhole for transportation:

It’s sort of pushing the edge of what is scientifically possible. It helps solve a problem. There is a big problem, if you’re going to have any kind of a fictional plot involving travel to other stars. If you do it with normal physics, it’s going to take hundreds of years. Who has the time for a movie that long? That’s the whole thing with Star Trek. We had warp drive.

Wormhole is sort of the modern version of warp drive. And, yeah, there are actually solutions to Einstein’s general relativity that produce these structures that have been called wormholes, where the geometry of space-time connects different places that in normal space are very distant in the universe. In theory, you can do that. The problem is, if you actually look at how that might work, it doesn’t really work. You’d end up ripping apart everything that went into the wormhole. It’s not like NASA is actually working on this. It’s a way to have your plot device fit the science.

In the movie, a scientist explains how a wormhole could make distant space exploration possible by placing a point at the top of a piece of paper and drawing a line to a point at the bottom. The bottom point, we are told, is very, very, very far from the top. Think galaxies apart. He then folds the paper in half so the points line up and punches a hole in the paper through both points. That hole is a wormhole. Is this, I asked Grinspoon, a scientifically accurate reflection of how space-time can bend?

I loved that scene. That’s exactly how a physicist would explain a wormhole…That is exactly how Kip Thorne would describe a wormhole, and he is the guy who came up with wormholes…That scene was great from a scientific point of view. That’s exactly how a physicist would explain it.

So the movie does take the science seriously? Well, Grinspoon says, not always:

Yes and no. Here I’m balancing my inner snob and my delight that people are interested in a movie on themes that I love. But there is a critique I can’t help but apply to this. The science is spotty. It’s interesting they had Kip Thorne involved. They paid a lot of attention to relativity and space-time. And yet there’s this whole other theme about what happens to the planet, what happens to the Earth, and these other planets. They go and find planets and there are conditions on them [not consistent with science]. The planetary parts of the film, I thought, were really weak. That’s my bailiwick.

For instance, they describe this ecological disaster on Earth. I like the fact they are talking about that and raising consciousness. It’s clear that it’s climate change and we screwed up the Earth…That’s a good theme. But the specific things they say about it—they say there’s this blight [attacking all crops] that’s building up the nitrogen [in the atmosphere] and that’s going to draw down the oxygen. Anybody who knows about planetary atmosphere is going to sit there at that point and go, “That’s a bunch of BS.” It’s not that that ruins the movie for most people. But why couldn’t they have run that by somebody? It wouldn’t change the plot…There are aspects to the planets they get to which also don’t make sense from basic physics. There’s a planet with ice clouds…That’s BS…Something like that would fall. Because of gravity! Is that so crucial to the plot? There’s a planet around a black hole…Some physicists might quibble whether that’s even possible or stable. But one obvious problem is, when they landed there it was daylight. But there’s no sun and a black hole doesn’t put out light. So where is the light coming from?

Is this being too picky? The filmmakers do try hard to show there is science underlying the seemingly impossible journey made. Yet at the end, several knotty plot dilemmas are resolved when—the most mild spoiler alert!—a character enters a black hole and is somehow able to communicate with others back on Earth and in the past. So, I put it to Grinspoon, is this science or…magic?

It’s on the fine line between science and magic…If you were at a cocktail party with a few physicists who had a few drinks, which I’ve been to, this is the kind of thing that comes up. And somebody said, “Name a subject that’s really on the edge between science and magic,” somebody will say, “Time travel through black holes.” You can find some equation when it sort of, maybe works. But, then, of course, if you have time travel, it introduces all these horrible paradoxes. What if you went back and told your mother not to marry your father?…In the movie I found it suspiciously close to magic. That was one thing that bothered me. It was kind of like they needed to tie up the plot: and, then there’s a black hole, and magical things happen, so everything is fine.

The ending was tough to figure. Can you really have a five-dimensional system manifested in a three-dimensional manner that allows someone to go back in time to the precise place he or she needs to be to save humanity? I confessed to Grinspoon that I was confused.

I kind of liked that aspect. I sort of like the fact that you are confused by that. Reality on that level is confusing. One of the weird things about modern physics is that we do find there are apparently these other dimensions that we don’t directly experience that explain some aspects of the overall geometry and reality of our universe. When you encounter the real physics of that stuff, you do get this feeling you are having now of going, “Well, that’s confusing, how could that be?” I’m not sure about the specific realism of how that was depicted. But I do like the idea that there’s a movie that is going to get people thinking, “Really? There could be other dimensions?” That is evoking something that people have when they encounter modern physics.

At first glance, Interstellar does seem to have a green message, warning that climate change could make the world uninhabitable for humans (and, presumably, other species). Yet there’s an odd twist. The tag line for the film is, “The end of the Earth will not be the end of us.” And the lead scientist, played by Michael Caine (no longer Alfred the Butler), says at one point: “We are not meant to save the world. We are meant to leave it.” In other words, if humans do trash the planet, don’t worry, some super-smart folks will help us make a nice get-away somewhere else in this swell and expanding universe. Given that Grinspoon researches life and planetary development, I wondered what he thought of this cut-and-run theme.

That tagline…is problematical. The reality is the opposite. It’s quite possible that the end of us will not be the end of the Earth. Even if we really screw things up and things go badly for us and our civilization, the Earth is pretty resilient. The current species here will have a mass extinction, but life will not extinguish and the Earth will recover and go on…We’re more fragile than life. And then there’s the moral implication: It doesn’t really matter, there are other planets out there, the heck with this one. I found that bothersome. Of course, in the very long run, if we are successful in getting through our current little problems of being a technological civilization, and we last for thousands, even millions and billions of years, ultimately the Earth and the sun will run their course. So if we become one of those super-wise beings that are implied in this film that make wormholes, at some point we will have to deal with the problem of moving.

That’s in the long run. The very long run.

To hear my full interview with David Grinspoon, listen to Inquiring Minds below:

Inquiring Minds is a podcast hosted by neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas. To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. We are also available on Stitcher. You can follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook. Inquiring Minds was also singled out as one of the “Best of 2013” on iTunes—you can learn more here.