In the sentencing phase of a death penalty trial, a good defense lawyer presents mitigating evidence. That’s information that may show that the defendant lacks the “extreme culpability” the courts require for execution—in theory, at least. He may be intellectually disabled (a.k.a. mentally retarded), a circumstance for which the Supreme Court has issued a blanket exception (although it is not always heeded). He may be insane, a harder-to-prove designation that applies only to certain defendants with severe mental illness. He may (and many do) have a history of severe trauma. Or he may simply be young. The Supreme Court has banned the execution of anyone under 18 at the time of his crime, although that, of course, is arbitrary. Lawyers for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was 19 when he helped his older brother carry out the Boston Marathon bombings, have spent the past couple of weeks arguing that he should be spared, essentially because he was a kid in the thrall of his brother, the alleged ringleader.

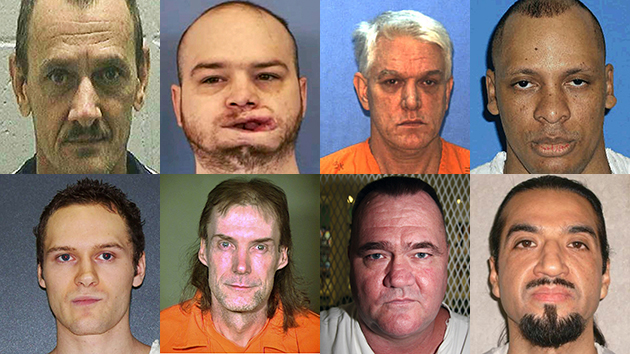

After scrutinizing all of the mitigating factors in 100 recent execution cases, legal researchers Robert Smith, Sophie Cull, and Zoë Robinson published their results in Hastings Law Journal last year. They concluded that only 13 of the 100 prisoners executed had actually met the legal criteria for extreme culpability. (To see why that didn’t save them, read my accompanying story: “87 Reasons to Rethink the Death Penalty.“) Below you’ll find brief summaries from eight of the cases they examined. Let’s assume that you believe the death penalty is warranted in some circumstances. Put yourself in the jury box, read these case details and ask: How would I have voted?

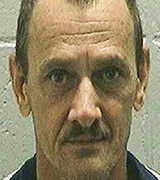

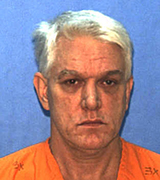

Name: Roy Willard Blankenship

Executed: Georgia, 2011

Mitigating factors: Trauma

Blankenship’s family had a history of mental illness. His uncle spent most of his life in an institution and his twin sisters had paranoid schizophrenia. Blankenship was raised by an abusive alcoholic father who regularly beat his mother, including when she was pregnant. The family was so poor they couldn’t afford a crib, so he slept in a dresser drawer. Days after his birth, Blankenship’s father came home drunk and slammed the drawer closed; the dresser fell over, nearly killing the infant.

In the years after his father and aunt died of carbon monoxide poisoning in a hotel room, Blankenship’s mother remarried three times. One of the stepfathers beat Blankenship frequently and tortured and killed his pets in front of him. A neighbor sodomized Blankenship when he was eight or nine, and when a witness reported these assaults to his mother, she beat her son. She later abandoned her children entirely. Blankenship was convicted and sentenced to death in 1978 for the murder of an elderly woman, whom he also raped.

Name: Elmer Carroll

Executed: Florida, 2013

Mitigating factors: Intellectual disability, trauma

Carroll started out at a disadvantage thanks to fetal alcohol syndrome. His parents were abusive alcoholics who found it amusing to feed their toddler booze until he got sick or fell down. His father once chopped up a live puppy in front of his kids. His mother was mentally ill and would beat her head against walls. According to court documents, she at one point threw Carroll’s brother, six at the time, “into” a woodstove, leaving him permanently scarred. She also would beat Carroll with a hickory stick until she passed out or grew too exhausted. She would also claim he was possessed by demons, and perform exorcisms on him.

By age six, Carroll himself was an alcoholic. When he was 12, a neighbor began forcing him to perform oral sex, and occasionally urinated on the boy’s face—the abuse lasted a year before the man was arrested. Carroll dropped out of middle school. As a teen, he was a serious drunk who experienced blackouts and hallucinations from binge drinking. He was later tested and determined to have brain damage as the result of the fetal alcohol syndrome, the beatings, and trauma from barroom fights—one of which caused a “significant head injury.” He also was diagnosed with borderline mental retardation that left him the intellectual equivalent of an 11-year-old.

Name: Elroy Chester

Execution place and year: Texas, 2013

Mitigating factors: Intellectual disability

From the age of seven up through his stint on death row for rape and murder, Chester was given five IQ tests. On four of them, he tested below 70, a score the Supreme Court has identified as strong evidence of intellectual disability. Chester spent most of his school years in special education, and never advanced beyond a third-grade level. When he was in prison, Texas enrolled him in its Mentally Retarded Offenders Program. Far from disputing his intellectual disability, the state argued that it was a compelling reason the jury should vote for death.

Name: Richard Cobb

Executed: Texas, 2013

Mitigating factors: Youth, trauma

Had Richard Cobb been born five months earlier, it would have been illegal to execute him. As is, he was born with brain damage due to alcohol exposure in the womb, which his lawyers argued made him effectively intellectually disabled. His mother would pick him up from daycare drunk—when she bothered to pick him up at all. It was mandatory daycare, ordered by child welfare authorities, and Richard and his brothers arrived there bruised, hungry, and underweight, according to the staff. One day after his mother left him there, a worker took Cobb home to find his baby brother home alone in a crib, covered in roaches.

Mental illness ran in the family; one brother was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, another with paranoid schizophrenia. Richard and his younger brother were taken from their mother when he was three and adopted to another family. When he was 16, his mother informed him that the man he knew as his father was not. Five months past his 18th birthday, Cobb was arrested with an accomplice for killing a man and shooting two others they’d taken as hostages in a convenience store robbery. He was executed at 29. After the drugs were administered, his final words were: “Wow! That is great. That is awesome! Thank you, warden! Thank you fucking warden!”

Name: Daniel Cook

Executed: Arizona, 2012

Mitigating factors: Trauma

The abuse Daniel Cook experienced was almost beyond comprehension. He started out with brain damage thanks in part to his manic-depressive mother’s substance abuse during pregnancy. He was sexually abused by his mother, father, and grandparents. His grandmother’s husband forced him to have sex with his sister, according to court documents, and his biological father burned his son’s penis with a lit cigarette—a crime Cook would eventually replicate in the rape and murder of a roommate that led to his death sentence.

Placed in foster care and group homes, he continued to endure horrific abuse: In one home, the adults would handcuff him to a bed in a “peek-a-boo room” with a one-way mirror, allowing others to watch while a foster parent raped him. The same foster parent forcibly circumcised him at age 15 and coerced other boys in the home to gang-rape him. Cook, not surprisingly, developed drug and alcohol problems and was hospitalized several times for trying to kill himself. His case was so extreme that the prosecutor who’d put him on death row tried to save him once his past came to light—which it never did at trial, since Cook had initially represented himself and asked for the death penalty. Arizona obliged.

Name: Cleve Foster

Executed: Texas, 2012

Mitigating factors: Trauma

Foster, who said he was routinely beaten with belts and tree branches as a child, saw his alcoholic father sexually abuse his brother repeatedly and later learned that his father had molested his sisters as well. He joined the Army and served in Operation Desert Storm. He was later diagnosed with PTSD and became a meth addict. When Foster was around 30, his brother was murdered. When he visited the crime scene with his mother after the burial, he discovered decomposing body parts missed by the people who had removed the rest of his brother’s corpse. He and another man were tried and convicted for the 2002 rape and murder of a woman they’d met in a Fort Worth bar.

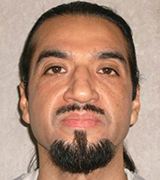

Name: George Ochoa

Executed: Oklahoma, 2012

Mitigating factors: Mental illness, mental disability, youth

Ochoa was 18 when he was accused of murdering two people during a home invasion. After his arrest, he was sent to a mental hospital for evaluation for psychosis, and his competency for trial was questioned. His lawyers argued that he was borderline mentally retarded. He also suffered from a neurological disorder, had abused inhalants and booze from an early age—which interfered with his mental development, his lawyers argued—and had brain trauma from a fall.

Before he was executed, his lawyers appealed to the federal courts for a stay because his mental state had deteriorated further in prison. They reported being unable to communicate with Ochoa because he’d become delusional and fixated on the voices he was hearing and his belief that he was being shocked all over his body all day long. Death row staff reported that Ochoa repeatedly kicked the toilet in his cell because he thought it was electrocuting him and that voices were coming out of it. He was so delusional that a defense psychiatrist couldn’t even evaluate him. The courts still deemed him sane enough to execute.

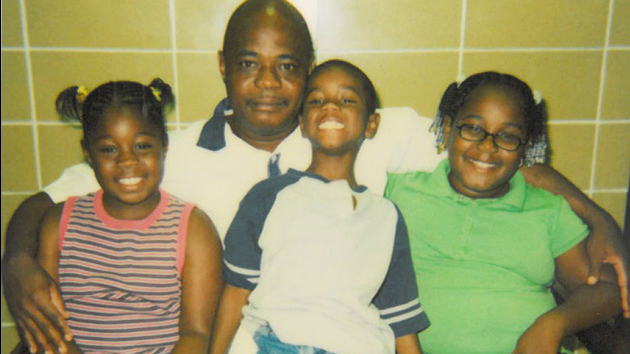

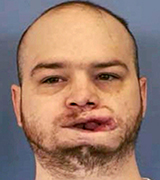

Name: Edwin Hart Turner

Executed: Mississippi, 2012

Mitigating factors: Mental illness, trauma, youth

Turner spent most of his life wearing a towel around his face to hide his disfigurement after he tried to kill himself with a rifle at age 18. His parents were abusive drunks, and his mother twice attempted suicide. His father died when Turner was 12 after shooting at a shed full of dynamite in what family members assumed was a suicide. (A friend from school called to say he’d seen police on TV putting pieces of Turner’s dad into garbage bags.) His mother hit the skids after that, drinking even more heavily. She married another abusive drunk, who beat her kids black and blue.

Turner’s grandmother and great-grandmother were both committed to mental institutions due to schizophrenia. By 15, Turner was showing symptoms of mental illness, too, and his mother twice took him to mental hospital for treatment. Two weeks after the second hospital visit he shot himself in the face. His parents eventually threw him out of the house, so he began living in a tent in the woods. He was repeatedly hospitalized for his mental illness in the four years after the first suicide attempt. Then, in 1995, he slit his wrists and was hospitalized for several weeks. He was released and then promptly sent back to the hospital for an involuntary commitment. After his subsequent release, with a prescription for Prozac, his behavior grew even more manic and bizarre. Doctors later confirmed he had bipolar disorder, a disease whose manic symptoms are exacerbated by Prozac. Six weeks later, at the age of 22, he murdered two people in a string of random convenience store robberies.