<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-248556931/stock-photo-modern-chicken-farm-production-of-white-meat-shallow-doff.html?src=zrGGITlen5KW2wjrWWuKdg-1-10">Avatar_023</a>/Shutterstock

The US poultry and egg industries are enduring their largest-ever outbreak of a deadly (known as pathogenic) version of avian flu. Earlier this month, the disease careened through Minnesota’s industrial-scale turkey farms, affecting at least 3.6 million birds, and is now punishing Iowa’s massive egg-producing facilities, claiming 9.8 million—and counting—hens. Here’s what you need to know about the outbreak.

Where did this avian flu come from? So far, no one is sure exactly sure how the flu—which has shown no ability to infect humans—is spreading. The strain now circulating is in the US is “highly similar” to a novel variety that first appeared in South Korea in January 2014, before spreading to China and Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, according to a paper by a team led by US Geological Survey wildlife virologist Hon Ip.

How did it spread? The most likely carrier is wild birds, but it’s unclear how they deliver the virus into large production facilities, where birds are kept indoors under rigorous biosecurity protocols. On Thursday, the mystery deepened when birds in an Iowa hatchery containing 19,000 chickens tested positive for the virus. “This is thought to be first time the avian influenza virus has affected a broiler breeding farm in this outbreak,” Reuters reported. “Such breeding farms are traditionally known for having extremely tight biosecurity systems.” John Clifford, the US Department of Agriculture’s chief veterinary officer, recently speculated that the virus could be invading poultry confinements through wind carrying infected particles left by wild birds, taken onto the factory-farm floor by vents.

Can humans catch it? So far, no. But public health officials have been warning for decades that massive livestock confinements make an ideal breeding ground for new virus strains. In its authoritative 2009 report on industrial-scale meat production, the Pew Commission warned that the “continual cycling of viruses and other animal pathogens in large herds or flocks increases opportunities for the generation of novel flu viruses through mutation or recombinant events that could result in more efficient human-to-human transmissions.” It added: “agricultural workers serve as a bridging population between their communities and the animals in large confinement facilities.”

Is this bird flu affecting the poultry industry’s revenue? Yup. The specter of flu is already pinching Big Chicken’s bottom line. China and South Korea—which imported a combined $428.5 million in US poultry last year—have imposed bans on US chicken, drawing the ire of USDA chief Tom Vilsack, Reuters reports.

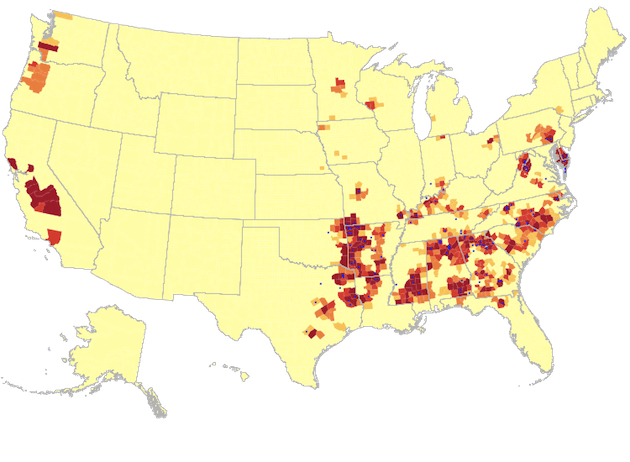

What’s the worst-case scenario? If the virus spread to the Southeast, Big Poultry will be in big trouble. Here’s a map showing where chicken production is concentrated (from Food and Water Watch). Already, the strain has turned up in wild birds as far south as Kentucky.

What are we doing to stop the flu from spreading further? All the flu-stricken birds not killed outright by the virus are euthanized—but beyond that, the strategy seems to be: ramp up biosecurity efforts at poultry facilities and cross your fingers. Flu viruses don’t thrive in the heat, so “when warm weather comes in consistently across the country I think we will stop seeing new cases,” USDA chief veterinarian Clifford recently said on a press call. But USDA officials recently told Reuters it’s “highly probable” that the virus will regain force when temperatures cool in the fall—and potentially be carried by wild birds to the southeast.