<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-292134134/stock-photo-hand-in-jail.html?src=-ERFTrGNlyeRTYTygiqqTA-1-0">Pikul Noorod</a>/Shutterstock

In 2005, when the Supreme Court struck down the use of capital punishment sentences for juveniles, it was a step toward greater legal recognition that children are different from adults—that young people’s changing brains and social vulnerability make them less culpable for their actions, and that because they are young, they have a greater chance at reform. Another step in this direction came in 2012, in the case Miller v. Alabama, when the justices ruled the use of automatic life-without-parole sentences for juvenile offenders was unconstitutional. Today, an estimated 2,230 people in the United States are serving life without parole for crimes they committed before they turned 18. (Read the story of Taurus Buchanan, who was automatically sentenced to life for throwing a single punch when he was in ninth grade).

Data collected by the Phillips Black Project, a nonprofit law firm based in San Francisco, reveals striking disparities among people who are serving juvenile life-without-parole sentences in different states. What’s more, the numbers, gathered through Freedom of Information Act requests between May and October last year, are almost certainly an undercount. (Read more about how the Phillips Black Project gathered and analyzed the data.) Because most states don’t track which sentences were imposed under mandatory sentencing schemes and which ones were discretionary, the numbers include all inmates serving juvenile life without parole in 2015.

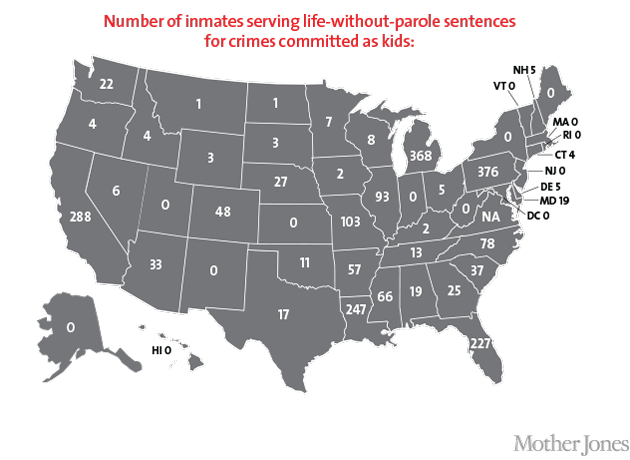

First, here’s where juvenile life-without-parole offenders are imprisoned:

What’s behind the geographic disparities? In part, the answer comes down to state policy and practice: A few places, like New York, have historically avoided imposing any juvenile life-without-parole sentences, while 16 states now ban it entirely. Other states used mandatory sentencing schemes for decades before the Miller v. Alabama decision. Meanwhile, most states still allow judges to impose a life-without-parole sentence at their discretion.

Yet the differences in numbers are even starker on a county-by-county level, says John Mills, Phillips Black’s lead researcher on the project. When it comes to throwing juveniles in jail with no chance for parole, the main culprits are officials in a handful of counties with a reputation for seeking and imposing harsh sentences on kids. Philadelphia alone is responsible for sentencing about 9 percent of America’s current juvenile life-without-parole inmates, Mills says, and the county used to be known for sentencing juvenile offenders to death: “I suspect that the same culture that led the prosecutor to seek a number of death sentences also informed [his or her] choices about juvenile life without parole.”

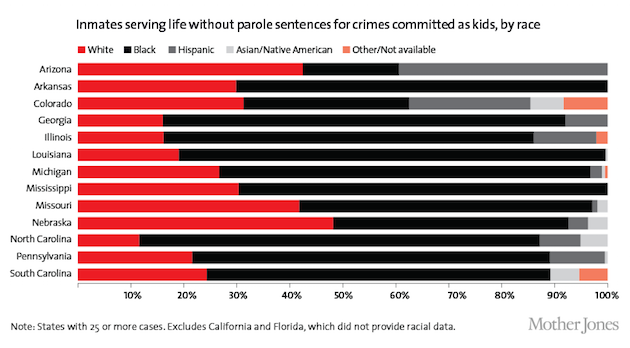

A prosecutor’s power comes from his or her decision of which charge—murder or manslaughter—to bring against a suspect, and, in some states, whether to transfer a suspect from juvenile to criminal court. (In some jurisdictions, anyone charged with certain serious crimes must be tried in criminal court, regardless of age.) According to Mills, this prosecutorial discretion is the most important reason why black and Hispanic youth offenders are overrepresented among the current juvenile life-without-parole inmate population:

Louisiana, with 247 juvenile life-without-parole inmates, has the highest number per capita of any state. But consider that while two-thirds of the state population is white, a whopping 81 percent of inmates who are serving juvenile life-without-parole sentences are black; in Arkansas, 80 percent of the population is white and 70 percent of juvenile life inmates are black. In Texas there are 17 people serving juvenile life without parole: 15 are black, 2 are Hispanic, and none are white.

In fact, since 1992, black children arrested for murder are twice as likely to end up sentenced to life without parole as white children arrested for murder, the Phillips Black Project found. That doesn’t account for policing practices, Mills points out. If police disproportionately arrest young black suspects over young white suspects, the disparity likely runs deeper than it appears.

“When we looked at the states that did provide us information about race, it was clear that who was receiving the sentences was troubling,” Mills says. “What we may be seeing is decision-makers discounting the youth of African Americans, and crediting white youth.”

The difference can be traced not only to prosecutors, but also to judges and juries, whose decisions may also be influenced by the race of the victim, Mills says: “If the lesson of the death penalty holds, that effect will be even greater when it’s a black defendant and a white victim.”

One strange outcome of the decision to end mandatory sentencing, in Miller v. Alabama, is that even though many fewer juvenile offenders now receive life-without-parole sentences compared with the late 90s, there is actually more opportunity for racial bias because sentences are now discretionary.

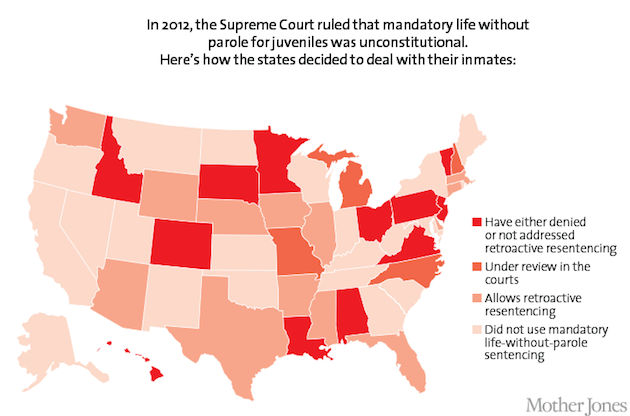

So what about those hundreds of people still behind bars under mandatory juvenile life-without-parole sentences? Since Miller, the states have reacted unevenly. Some, like Louisiana and Pennsylvania, have decided Miller is not retroactive—that is, the automatic sentences imposed before 2012 are still legitimate. Others, including California and Florida, have passed laws and made rulings that allow offenders who received mandatory sentences before Miller to be resentenced. Here’s the policy breakdown:

A case pending before the Supreme Court, Montgomery v. Louisiana, will address Miller‘s retroactivity in the coming weeks. Mills estimates that half of all inmates currently serving juvenile life without parole could become eligible for resentencing—at least 1,000 people. And many more could become eligible if states also apply the ruling to de facto “life sentences” that keep juvenile offenders in jail until they die of old age. That’s the case in Florida, where a state Supreme Court ruling on Miller’s retroactivity last spring qualified about 1,700 offenders for resentencing, according to the Tampa Bay Times.

Even if the Supreme Court decides the Miller ruling does not have to be applied retroactively, we can expect to see changes in the national population of juvenile life-without-parole inmates, Mills says, because the legal process to get a new sentence is laborious. This means that a lot of inmates who currently qualify for new sentencing hearings in states that applied Miller retroactively are still in prison, waiting for their cases to be heard. These inmates may also face challenges in obtaining skilled legal representation, Mills says. Inmates may not be eligible for a public defender until after they’ve successfully petitioned the state to grant them a hearing. Some of the cases are more than decade old, requiring a high degree of expertise to argue. (Public defenders in Florida are seeking additional funding to take on the case load, while the Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers has run seminars on how to argue a resentencing proceeding.) All that said, inmates still run the risk of being resentenced to life without parole, even after they’ve been granted a hearing.

Despite the difficulty of the resentencing process, the mere shot at a lesser sentence offers hope. And this time around, judges will have to account for the offender’s youth at the time of the crime. Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan wrote in Miller, “Given all we have said…about children’s diminished culpability and heightened capacity for change, we think appropriate occasions for sentencing juveniles to this harshest possible penalty will be uncommon.” Whether the Supreme Court will allow that hope for inmates serving juvenile life-without-parole sentences across all states remains an open question.