RyanKing999/iStock

Poverty was down in the United States last year and so was the number of Americans without health insurance. Our median household incomes had their best one-year increase ever, topping $56,500—the highest level since 2007, just before the Great Recession.

New figures released this week by the US Census Bureau show that many Americans are finally reaping the benefits of the nation’s economic recovery. The changes accompany a year of job growth—unemployment dropped from 6.2 percent in 2014 to 5.3 percent in 2015—and modest raises to minimum wages in 21 states and DC, notes Sheldon Danziger, president of the Russell Sage Foundation. Danzinger says he also anticipates a “modest gain” in growth for 2016. “The good news is the economy is moving in the right direction. We’ve recovered almost all the ground lost during the Great Recession,” he says. “The bad news, of course: We’ve got a long way to go to get people at the bottom and in the middle to where they were at the turn of the century.”

Here are some highlights from the new Census data:

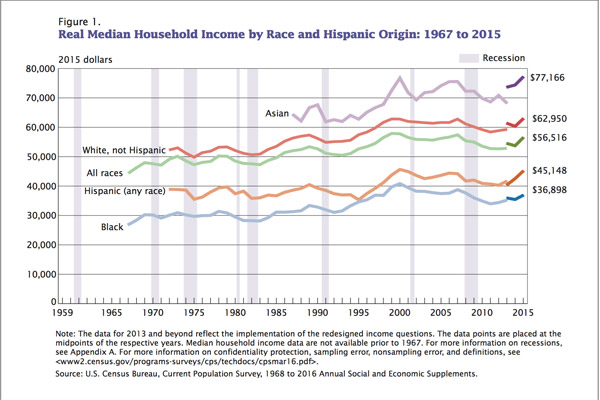

Raises for most: Americans across the board benefited from increases in household income from 2014 to 2015, regardless of their race, gender, age, or legal status. Hispanic families saw the largest gains (6.1 percent) in median household income, followed by white families (4.4 percent) and black families (4.1 percent). Still, those incomes remained below their pre-recession highs.

The gender pay gap decreased, if barely: In 2015, women earned 80 cents for each dollar earned by men, up a penny from the year before. A woman working full-time in 2015 earned $40,742, a 3 percent bump from 2014, but still $10,000 less than what the median man made.

Black and Hispanic women fared better compared with men of the same race. Among Hispanics, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, women made 87 cents to a man’s dollar. Black women earned 88 cents. But when compared with white men, Hispanic women made 54 cents per dollar, while black women earned 63 cents.

The poor and the middle class gained—but the rich gained more: While median household incomes rose at a higher rate for poor and middle-class families, the rich reaped far more in absolute terms. For example, a 5.2 percent income gain netted middle-class families an extra $2,798, while the 3.7 percent gain by the top 5 percent brought those households an additional $7,656 each. What’s more, the household earnings of those rich families were up 6 percent over their pre-recession earnings in 2007, whereas the earnings of the bottom 60 percent of households remain lower today than they were in 2007. (Scroll over the chart below to see the dollar amounts.)

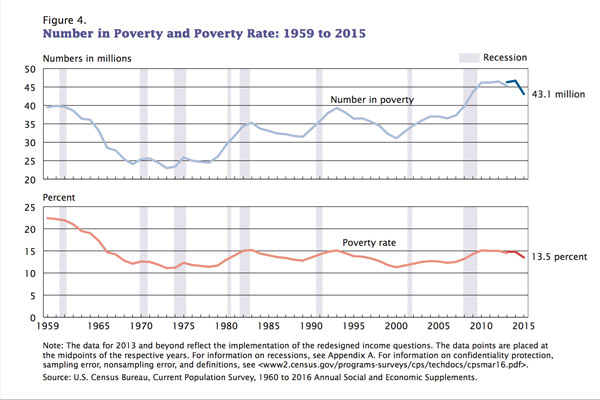

America’s poorest got a lift: Though 43 million people remained in poverty in 2015, including 14.5 million children, America’s poorest saw their biggest gains since 1968, an indication that job growth is reaching the bottom rung. “When jobs become available, the penetration of work into the poorest of the poor is really deep,” Kathryn Edin, a sociology professor at Johns Hopkins University and co-author of the book $2 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America. “You’re not going to get out of poverty if you’re not working full time.” Last year, the US economy gained more than 2.6 million jobs, the second-highest increase since 1999.

Meanwhile, the number of people living in poverty dropped by 3.5 million, falling from a bit under 15 percent in 2014 to 13.5 percent in 2015, the largest dip since 1967. More than 8 million families were in poverty last year, down from 9.5 million in 2014. And the number of children under 18 dropped by 1 million. For the first time, the Census Bureau also calculated poverty rates based on people’s actual take-home income—taking into account tax credits and government subsidies such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. (The poverty rate is normally calculated based on pre-tax income only.) And while more than 2 million additional Americans were impoverished based on the alternate calculation, 3 million children fell out of poverty.

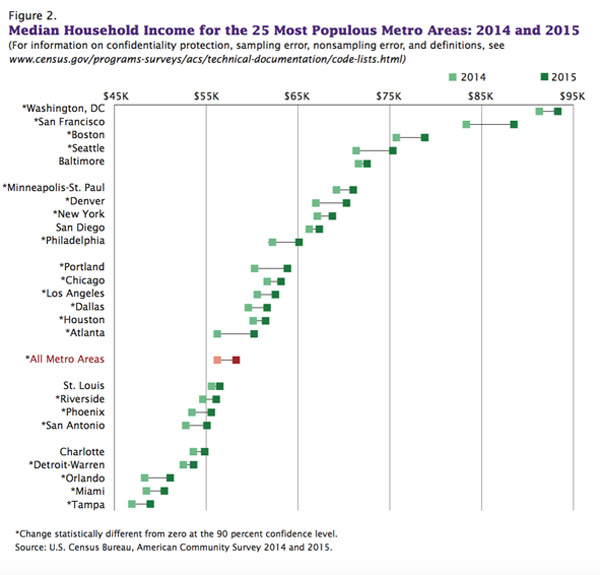

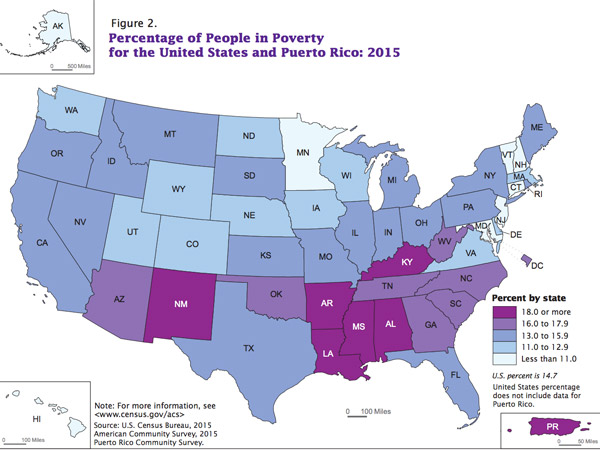

City dwellers got an economic boost, but rural America remained stagnant: Twenty-three states saw declines in their poverty rates. Mississippi maintained the nation’s most impoverished state, with 22 percent living in poverty, while New Hampshire saw the lowest rate—8 percent.

Much of the economic growth was confined to cities, however. Household incomes in cities within metropolitan areas grew 7.3 percent and poverty rates dropped. Rural dwellers—those outside the Census’ metropolitan areas—saw a 2 percent decline in median household income, and about the same rate of poverty as city dwellers.