Joe Papeo/Rex Shutterstock via ZUMA Press

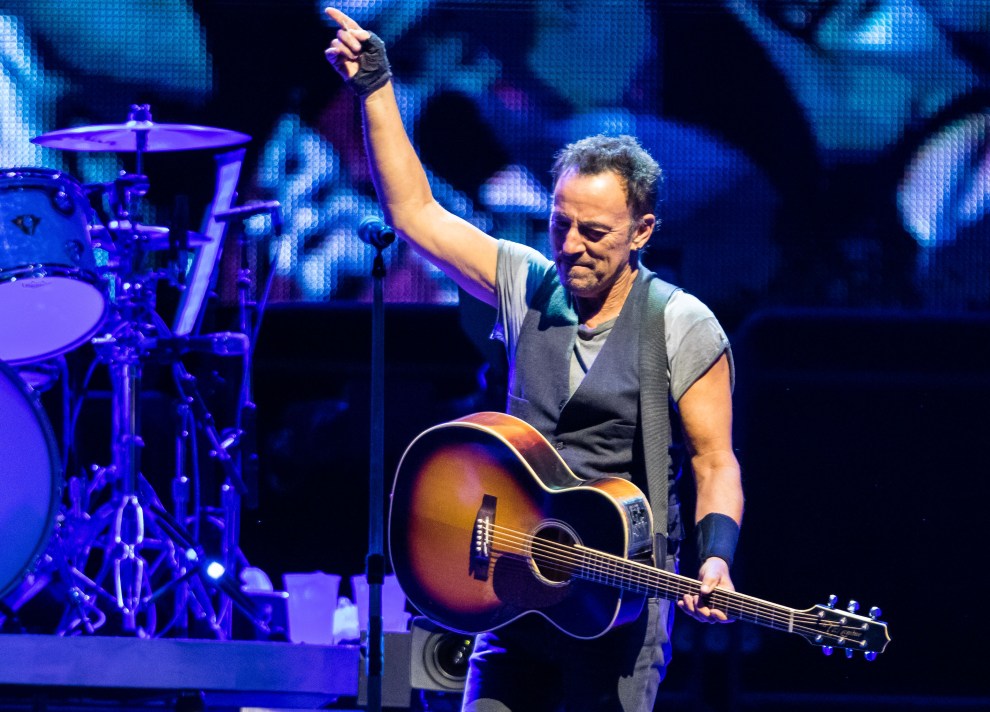

The fall of the Berlin Wall has been attributed to lots of things, from Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms and Ronald Reagan’s famous plea to the ineptitude of the Politiburo and the collective courage of the East German protesters. But there’s little doubt that David Bowie and Bruce Springsteen did their own small part.

When Bowie died this past January, the German Foreign Office noted as much in a memorial tweet: “Good-bye, David Bowie. You are now among #Heroes. Thank you for helping to bring down the #wall.” For Springsteen’s role, you can read the 2013 book Rocking the Wall: Bruce Springsteen—The Berlin Concert That Changed the World. But Springsteen’s recent memoir, Born to Run, offers his full account of that epic concert for the first time.

Many Americans are surprised to learn that our rock stars were even allowed to play in East Germany while the wall, constructed in 1961, remained in place. But Communist Party leaders, noting the tremendous buildup of anger and tension among their young people during the Gorbachev “glasnost” era, decided to provide a safety valve of sorts by allowing major rock concerts starting in 1987. Tens of thousands of East German kids were already flocking to the wall to listen as Bowie and others played just on the other side—and there had been clashes between the music-starved youth and East German police.

Bowie’s June 1987 performance was remarkable on several levels. The stage was set up in West Berlin, very close to the wall, with the old Reichstag building as a backdrop. Unlike most Western performers, he had a fitting song for the occasion: “Heroes,” written a few years earlier and purportedly inspired by Bowie’s time living in Berlin. The line about standing by the wall while “the guns shot above our heads” may refer to dramatic attempts by East Germans to escape the East—which happens to be the subject of my new book, The Tunnels: Escapes Under the Berlin Wall and the Historic Films the JFK White House Tried to Kill. (You can watch Bowie’s performance that day on YouTube.) And here, from a 2003 interview, is how he described it:

It was one of the most emotional performances I’ve ever done. I was in tears…And there were thousands on the other side that had come close to the wall. So it was like a double concert where the wall was the division. And we would hear them cheering and singing along from the other side. God, even now I get choked up. When we did “Heroes” it really felt anthemic, almost like a prayer. However well we do it these days, it’s almost like walking through it compared to that night, because it meant so much more. That’s the town where it was written, and that’s the particular situation that it was written about.

By then, Bob Dylan had been invited by a youth arm of the Communist Party to play in Treptower Park in the East on September 17, 1987, along with touring mates Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and Roger McGuinn. Protests were building against the regime and the wall, and East German officials hoped to defuse tensions with a few signs of openness.

Naturally, the Stasi (East Germany’s notorious secret police) were on top of it. Their six-page preview was filed at their headquarters under “Robert Zimmerman, No. HA XX 17578.” It mainly covered logistics and security—no secret bugging of Dylan, apparently—and the dispersal of 81,000 tickets, with at least one-third going to party officials and their pals. The Stasi didn’t seem too worried that Dylan, then in a down period in his career, would prove to be a rabble-rouser, as he was merely “an old master of rock” with no particular “resonance” with the youth of the day. The crowd, they predicted, would be mostly middle-aged and older. Dylan would act in a “disciplined” way and not cause undo “emotions.”

In the end, the gig played out pretty much as the Stasi had anticipated. By most accounts, Dylan—whose lyrical work just earned him the 2016 Nobel Prize for literature—gave a rather lackluster performance (his norm for the time), consisting of a couple of Christian tunes mixed in with hits like “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Rainy Day Women” and “Like a Rolling Stone.” He reportedly did not speak a single word from the stage.

This was not the case with Springsteen, who arrived in East Berlin 10 months later to play his biggest concert ever. More than 200,000 showed up, twice what Dylan had attracted. Springsteen opened, pointedly, with “Badlands,” but the indisputable highlight was his cover of “Chimes of Freedom,” a Dylan tune that Dylan himself had overlooked. The show, which in typical Springsteen style lasted nearly four hours, was beamed to millions of East Germans via state television. Many middle-aged Germans I interviewed for my book fondly recalled attending the performance or watching it on TV. “It was a nail in the coffin for East Germany,” one fan told the Guardian years later.

In Born to Run, Springsteen recounts a previous visit to East Berlin with bandmate Steve Van Zandt. “You could feel the boot,” he recalls. The wall, in Springsteen’s view, seemed almost “pornographic.” The experience helped shock the then-apolitical Van Zandt into decades of activism. “The power of the wall that split the world in two, its blunt, ugly, mesmerizing realness, couldn’t be underestimated,” Springsteen writes. “It was an offense to humanity.”

When Springsteen returned to East Berlin for his epic 1988 show, as I note in my own book, he unhappily discovered that the state was billing it as a “concert for the Sandinistas,” the pro-Communist Nicaraguans. So he delivered an impassioned speech. His German was grade-school level, but he got the point across: “I’m not here for any government. I’ve come to play rock and roll for you in the hope that one day all the barriers will be torn down.” East German officials backstage had somehow learned about Bruce’s original statement, which included the explosive word “walls,” and Springsteen’s manager, Jon Landau, had convinced him at the last minute to change it to “barriers.” But after finishing his statement, Springsteen quickly launched into “Chimes of Freedom,” which includes the key reference: “while the walls were tightening.”

The next day, he and the band “partied” at the East Berlin consulate, Springsteen writes, before heading back to the West to play a show for a mere 17,000 people—which “felt a lot less dramatic than what we’d just experienced.” Referring to the “stakes” of rock and roll, he writes, “The higher they’re pushed, the deeper and more thrilling the moment becomes. In East Germany in 1988, the center of the table was loaded down with a winner-take-all bounty that would explode into the liberating destruction of the Berlin Wall by the people.”

German historian Gerd Dietrich would later tell Rocking the Wall author Erik Kirschbaum, “Springsteen’s concert and speech certainly contributed in a large sense to the events leading up to the fall of the wall. It made people more eager for more and more change,” he said. “Springsteen aroused a greater interest in the West. It showed people how locked up they really were.”

As Springsteen himself would later put it, “Once in a while you play a place, you play a show that ends up staying inside of you, living with you for the rest of your life. East Berlin in 1988 was certainly one of them.”

Greg Mitchell is the author of The Tunnels: Escapes Under the Berlin Wall and the Historic Films the JFK White House Tried to Kill.