Mike McQuade

When I was about 10, a classmate in my small-town school in Latvia liked to tell me in between classes that he hated Jews. I was the only Jewish kid in school, and one day as I walked home I heard steps behind me. My eyes caught his, and we stood there for a moment. I still remember his face—hazel eyes, closely cropped blond hair—and his navy uniform jacket over a white shirt. Suddenly, I heard a crunch as his fist landed on my left cheekbone, and I fell backward on a sidewalk damp with melting snow. I still remember the hollow ringing in my left ear. I looked around to scream for help, but the streets were empty. I’ve never felt more terrified and alone.

“There is nothing we can do to change him,” my father said in our garage the next day. He wore a large black boxing glove on his left hand that he made me practice hitting late into the night. “You have to throw the punch from your shoulder, and pack the weight of your entire body into it,” he said. “As soon as you show any fear, you’ve already lost.”

My mother and I eventually left Latvia, and bullying was a big reason for me. It’s been 22 years since I’ve thought about this particular incident—but the recent surge of media reports about xenophobic language and harassment across the United States brings those old fears roaring back. And now that we have an administration that has welcomed into the White House advisers with a long history of promoting Islamophobia and boosting white nationalists, I find myself wondering what that means for today’s bullies and their victims.

Extreme views can be socially contagious, especially among young people, who are more susceptible than adults to being influenced by their peers. As a journalist, I report on schools, and teachers have been telling me that violent rhetoric is more common, and that they’re struggling to find the right approaches to root it out. But some educators are also part of the problem. In a 2015 survey, 1 in 5 Muslim students in California said they experienced discrimination by a school staff member. According to a complaint filed by the American Civil Liberties Union last year, when a Muslim sixth-grader from Somalia raised his hand to answer a question, a teacher at a school in Phoenix snapped, “I can’t wait until Trump is elected. He’s going to deport all you Muslims…You’re going to be the next terrorist, I bet.” (The school denies these allegations.)

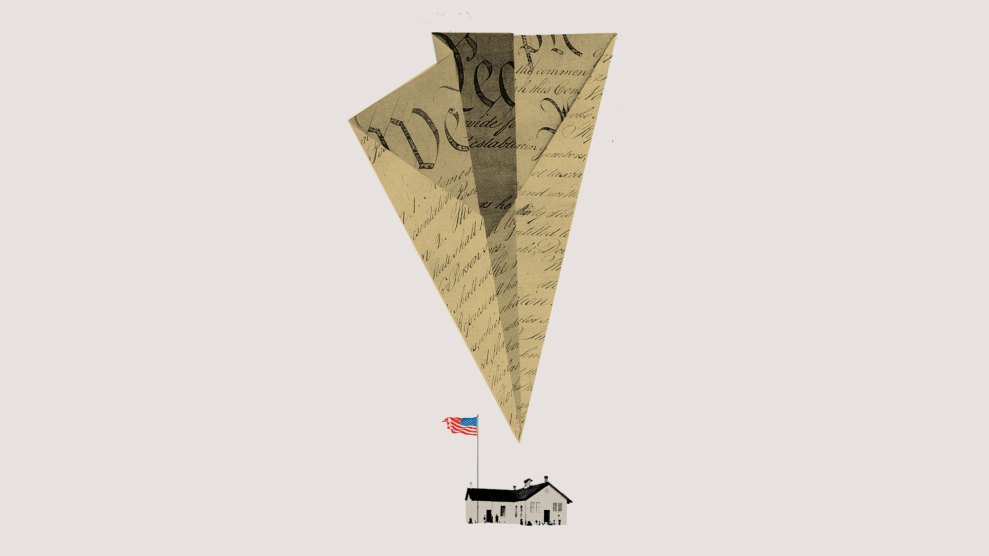

Such behavior is a far cry from the ideals of American public schools, which were founded to maintain a pluralistic democracy and protect citizens against the tyranny of the majority. Advocates for the public education system argued that the unique American experiment wouldn’t work without it—that schools were the most effective mechanism for instilling civic values such as abandoning unrestrained self-interest and opposing bigotry.

Until the late ’60s, three different courses in civic studies were common in American high schools, and they often focused on helping students apply the dry mechanics of government to solving problems in their own communities. Many social studies classes also aimed to highlight the fragility of the democratic process and the historic importance of civic engagement.

True, these classes were often heavy on jingoism and light on people of color, women, and LGBT communities, but that in itself prompted a civics lesson: a powerful movement for ethnic and gender studies that continues to expand.

But all that changed most notably in the 1980s, when, in addition to earlier cuts in civic studies, policymakers began shifting the focus from social studies toward easily testable subjects like math and reading. As Stanford University’s David F. Labaree argued in his intellectual history of American education, Someone Has to Fail, schools abandoned their civic mission in favor of preparing a new generation of skilled workers. The No Child Left Behind Act later accelerated this push, drawing on the work of a Reagan-era commission that postulated (with scant evidence) that test scores in reading and math would predict college and workplace performance.

In 2011, all federal funding for civics and social studies was eliminated. Some state and local funding dropped, too, forcing many cash-strapped districts to prioritize math and English—the subjects most prominently featured in standardized tests. A study by George Washington University’s Center on Education Policy found that between 2001 and 2007, 36 percent of districts decreased elementary classroom time spent on social studies, including civics—a drop that most affected underfunded schools serving working-class, poor, rural, and inner-city kids.*

In Detroit, for example, a veteran teacher named William Weir has struggled to keep civic education alive amid mandatory tests and funding cuts. Over the last three years, Weir’s school has lost its music, arts, and gym classes, as well as its teaching aides. Even though Weir is a social studies teacher, the principal asked him to teach English because it’s a tested subject. (The gym teacher became the new social studies teacher.) Meanwhile, Weir’s classes grew from 25 students to as many as 36.

Despite all this, Weir—who previously worked as a police officer—says teaching is the best job he’s ever had because he finds meaning in helping his students develop a sense of agency and confidence. Last year, Weir taught a course called “Take a Stand.” Students read about Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Cesar Chavez, and after a few weeks he assigned them a research project he had designed himself. “What would you like to take a stand on?” he asked a packed room of third- and fourth-graders. “I really miss our music and gym classes,” one student replied. “Why don’t we have them anymore?” asked another.

So Weir’s students read studies about the cognitive, physical, and emotional benefits of music and gym classes. They researched their school district’s financial woes, budget cuts, and emergency managers. Then they held a protest in front of the school and wrote letters to their federal, state, and local officials. With additional funding and a reduced testing burden, Weir told me, he could incorporate many more hands-on, relevant civics lessons like these.

The good news is that help may be on the way: The ideology of how to teach American history and civics might vary, says Ted McConnell, executive director of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, but there is strong bipartisan support for expanding social studies. If recent research is any indication, that support couldn’t come a moment sooner. When, in 2011, the World Values Survey asked US citizens in their late teens and early 20s whether democracy was a good way to run a country, about a quarter said it was “bad” or “very bad,” an increase of one-third since the late 1990s. Among citizens of all ages, 1 in 6 now say it would be fine for the “army to rule,” up from 1 in 16 in 1995. In a different national survey, about two-thirds of Americans could not name all three branches of the federal government or which party controlled the House of Representatives. In a third study, almost half of the respondents said the government should be permitted to prohibit a peaceful march.

Educator, author, and civil rights activist Jonathan Kozol has spent the past five decades writing about public schools. “Civic education should be empowering young people to ask discerning questions, and to feel that it’s okay to challenge the evils and injustices they perceive,” he said. But “civic engagement is being beaten out of kids by this tremendous emphasis on authoritarian instruction, and part of it is [the emphasis on] one right answer on the test. We need to empower young people to understand that the most important questions we face in life have limitless numbers of answers and that some of those answers will be distressing to the status quo.”

I’ve seen that work firsthand, at some of the country’s most diverse and equitable schools. I spent four years observing classes at San Francisco’s Mission High School, a destination for immigrants from more than 40 countries. There, civics is an integral part of instruction not only in history, economics, and ethnic studies classes, but also in literature classes, where students are asked to consider how people from different eras and cultures interpreted the meaning of empathy, courage, and collective responsibility.

Mission High students are also encouraged to practice civic engagement skills by serving on the youth advisory council that helps the principal make decisions about course offerings and the budget, and by meeting with school board members to provide feedback on how to make the city’s classrooms more effective for all students.

On countless occasions, I saw students show me, their peers, and other adults what it means to derive power from a sense of community, moral generosity, and an ability to integrate multiple perspectives—instead of via competition, threats, or exclusion.

One winter morning I watched students discuss a film based on the 1968 protests of thousands of Latino public school students in East Los Angeles. While the class went over the movie’s themes—courage to take a stand, commitment to collective goals, the importance of community support—a girl named Brianna jumped in.

“Speaking of stereotypes,” Brianna told her classmates, “I was in the bathroom with five other black girls, and we were fixing our hair. Two Asian American girls come in and they run out right away, thinking that we are going to bully them. I want to fix that. I’m a nice person!”

Brianna’s social studies teacher, Robert Roth, turned to another student and asked, “Rebecca, you were talking to me about this kind of stereotype the other day. Do you mind sharing what you said?”

“When we moved to St. Louis from China,” Rebecca said, “we went to an all African American school. My parents were telling me to stay away from black students. But African Americans were all really nice to us.”

She paused. “A lot of times, it’s coming from parents. But they just don’t know. My parents never met any black people in China.”

“Most parents,” George, a recent immigrant from China, said quietly. Then, in a slightly more confident voice, he added, “It’s not about the ethnicity. It’s about the person.”

“I love George,” Brianna said with a hand on her heart, as students shifted to the next activity.

When I observed moments like these, I felt a sense of regret that I was often the only white person in those classrooms. Kozol has long warned us about what’s lost when opportunities for learning mutual understanding disappear through resegregation. By most measures, our public schools today are more racially segregated than they were shortly after Brown v. Board of Education was decided, according to the Century Foundation, and white children are growing up in incredibly homogeneous environments: The average white kid goes to a school where 77 percent of students are white, and she is less likely than a student of color to interact with students from different racial or ethnic backgrounds.

Even three years after I finished my reporting at Mission High, these manifestations of deeper understanding burned in my memory more than any lessons of diversity and tolerance from lectures, history books, and pop culture. They can’t be conveniently translated into grades, test scores, and acceptance letters to elite colleges. But for many people like me, who left our homes, our best friends, our grandparents’ graves to be in a country that has a history of struggle for freedom and opportunity for all, their value is obvious.

*This sentence has been corrected to more accurately reflect the data available on classroom time spent on civics.