Throughout the retrospective for photographer Walker Evans at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the 400 photos and pieces of art radiate with a warm sense of familiarity. Visitors may recognize specific, iconic images, but the feeling also comes from Evans’ fixation on the American vernacular, a driving theme in the organization of this show. The two full galleries that make up the exhibit create the sense that one is stepping into a well-curated time-capsule of a faded but still thoroughly recognizable America.

Roadside Stand Near Birmingham/Roadside Store Between Tuscaloosa and Greensboro, Alabama, 1936.

Walker Evans, collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

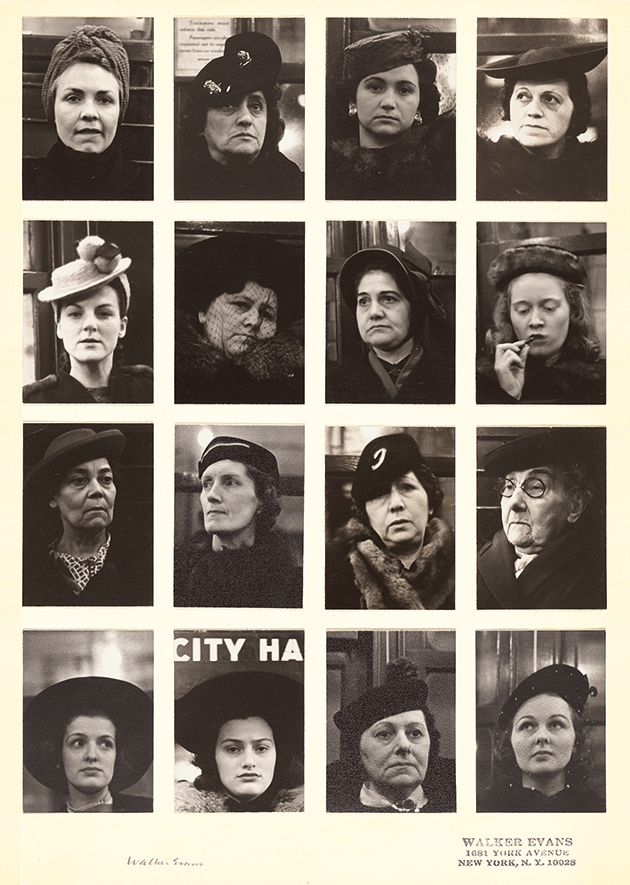

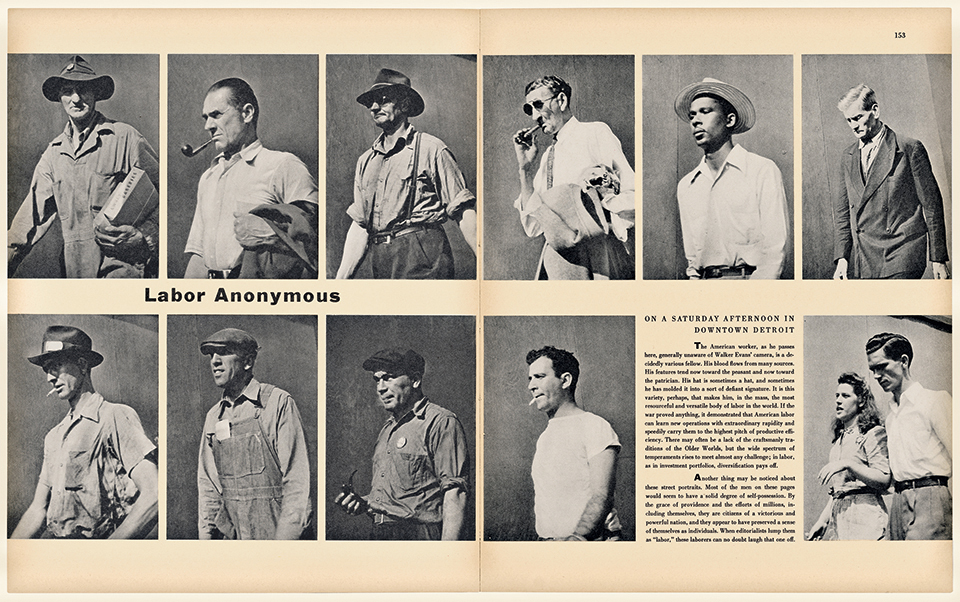

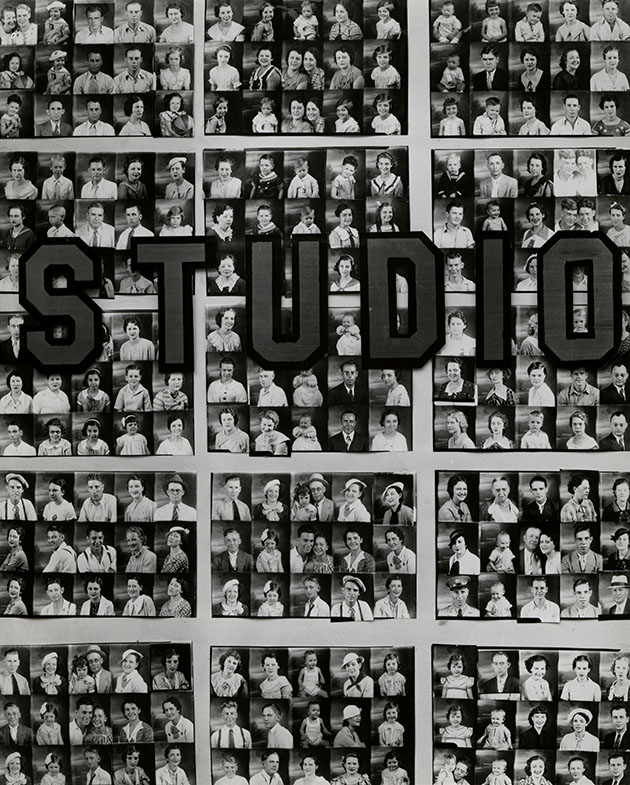

As a photographer, Evans was fascinated by everyday things, objects, and people—advertisements, catalogs, storefronts, street debris, graffiti, workers, strangers—that tend to blend into the background for most of us. He documented life around him, the monumental and mundane—photographing billboards as if he were collecting them, photographing Main Street as if he were shooting a postcard, secretly photographing fellow subway passengers, and making striking images of laborers going to or coming home from work. He studiously photographed junkyards and churches and trash in the street, relishing repetition in the everyday.

He documented America in a way that belies his obsessive collecting tendencies. The exhibit does an excellent job of mixing Evans’ photographs with the ephemera he collected as inspiration, from rusted, shot-up road signs to movie posters.

Main Street, Showing Confederate Monument, Lenoir, North Carolina, 1900–40.

Lenoir Book Co., collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Walker Evans Archive; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Main Street, Saratoga Springs, New York, 1931.

Walker Evans, private collection, San Francisco; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Subway Portraits, 1938–1941.

Walker Evans, collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

“The Pitch Direct. The Sidewalk Is the Last Stand of Unsophisticated Display,” Fortune 58, no. 4, October 1958.

Walker Evans, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Collection of David Campany; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Allie Mae Burroughs, Wife of a Cotton Sharecropper, Hale County, Alabama, 1936.

Walker Evans, private collection; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

To be sure, Evans wasn’t a photographer who shot one thing, one way. He played with the medium at a time when it was still young, yet to be fully defined.

He was also a documentarian and a photographer for Fortune magazine. In 1936, he and writer James Agee went to Alabama to document the life of tenant farmers during the Dust Bowl, a project that became the landmark book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The mix of reportage and portraiture by Evans, combined with Agee’s writing, set the tone for what the entire documentary genre could and should be.

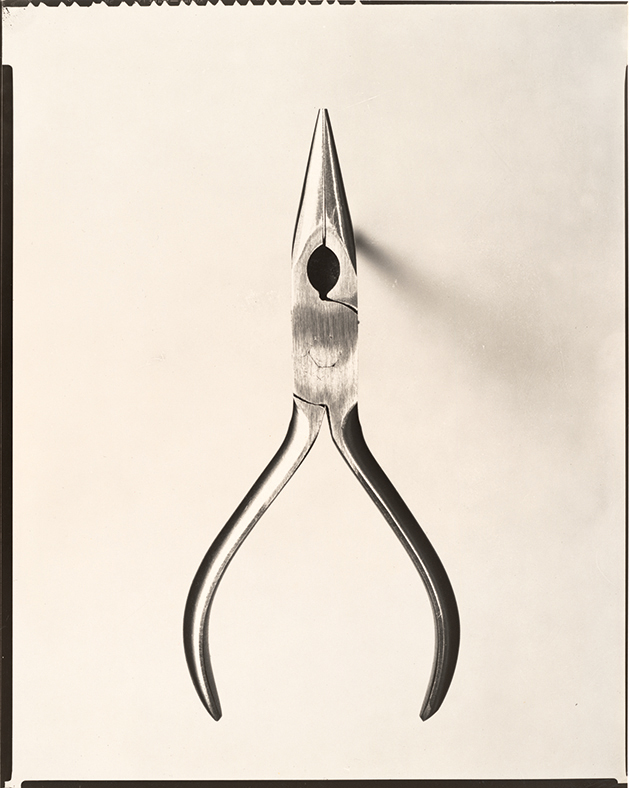

Contrasting his documentary work, Evans’ fascination with catalogs, specifically tool catalogs, led him to produce a portfolio of fine-art-level still life images of common work items—wrenches, pliers, screwdrivers. As boring as that may sound, the work still resonates with strong, simplistic beauty.

Chain-Nose Pliers, 1955.

Walker Evans, The Bluff Collection; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Resort Photographer at Work, 1941.

Walker Evans, collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

That sense of familiarity in the exhibit also comes from the fact that Evans’ influence bleeds all through 20th-century photography. It’s hard not to see reflections of other, later photographers’ work in Evans’ photos. You catch a whiff of Warhol in Evans’ early nod to pop art, collecting and photographing advertisements, as well as in his early-’70s Polaroid snapshots of friends and family. A photo of a tourist photographer at work reeks—in the best way—of Robert Frank or Garry Winogrand, two great street photographers and chroniclers of America themselves. And Evans’ photos of riders on the New York Subway—some of his earliest and most memorable—bring to mind Helen Levitt, Lee Friedlander, Bruce Davidson, and, notably, Luc Delahey, whose 1999 book L’Autre, shot in the Paris Metro, strongly evokes Evans’ repetitious collection of subway rider images.

Meanwhile, Evans’ fascination with postcards instantly recalls Martin Parr’s own collection (and subsequent publication) of Boring Postcards. The Alabama tenement photos inspired generations of photographers; Eugene Richards’ early work in the South can be considered a direct lineage. It’s no coincidence that Evans was also an early, vocal champion and mentor to many of these photographers.

Penny Picture Display, Savannah, 1936.

Walker Evans, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Collection of David Campany; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

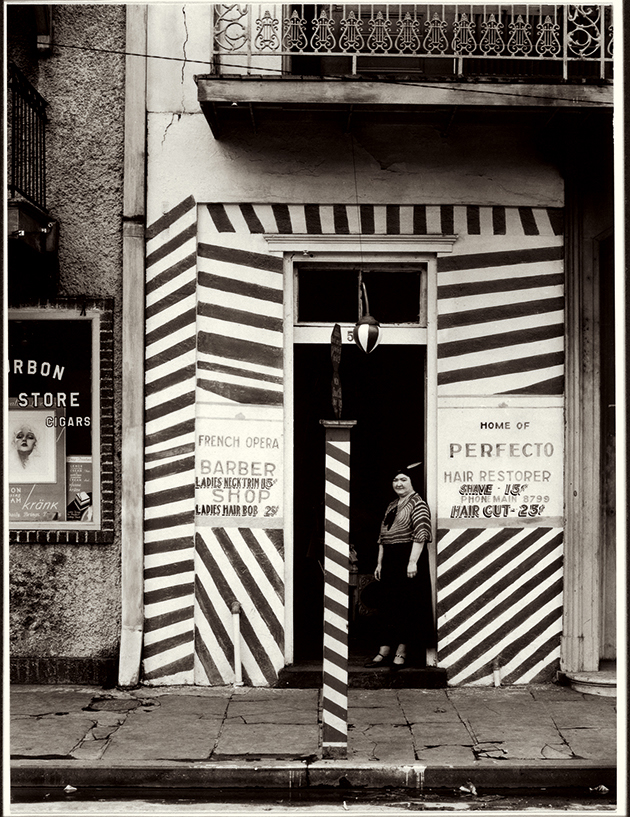

Sidewalk and Shopfront, New Orleans, 1935.

Walker Evans, collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of Willard Van Dyke; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Street Debris, New York City, 1968.

Walker Evans, private collection, San Francisco; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It’s not always the case that Evans did it first or even best. But this robust exhibit—first put together for the Musée National d’Art Moderne of Centre Pompidou in Paris, and which is only showing in the United States in San Francisco—still makes it seem that way. The show, with its 300 or so original prints and 100 documents from Evans’ collections, drives the point home that Evans set the mold for American photography; as senior SFMoMA curator Clément Chéroux put it, he is the “quintessential American photographer.”

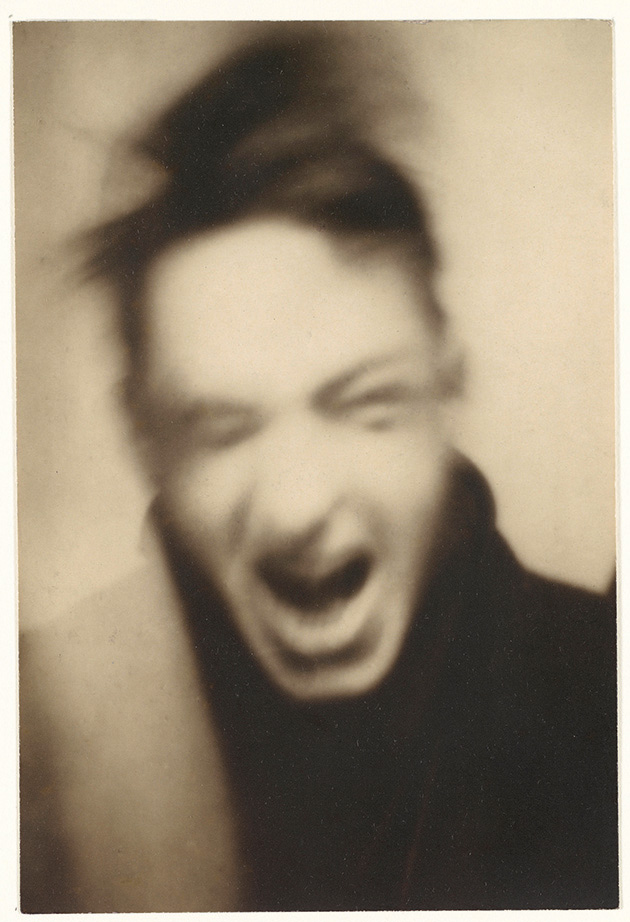

Self-Portrait, 1927.

Walker Evans, collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Interior of Walker Evans’s House, Fireplace with Painting of Car, 1975.

John T. Hill, private collection; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Subway Portrait, 1938–41.

Walker Evans, collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans can be seen at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, September 30, 2017, through February 4, 2018. An accompanying catalog, published by Prestel, is also available.