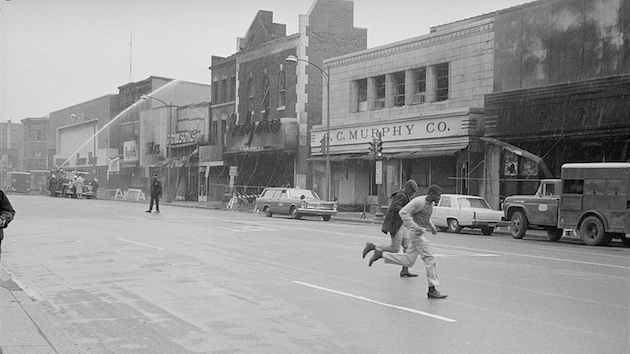

Warren K. Leffler/Library of Congress

For a moment, the peace seemed to hold. It was the evening of April 4, 1968, and Martin Luther King Jr. had just been killed by a gunman in Memphis. An angry crowd had gathered at 14th and U streets NW, the nexus of African American commerce and culture in Washington, DC. The demonstrators were making a simple request of local shopowners: Shut down to pay your respects. The owners readily complied. The crowd moved on.

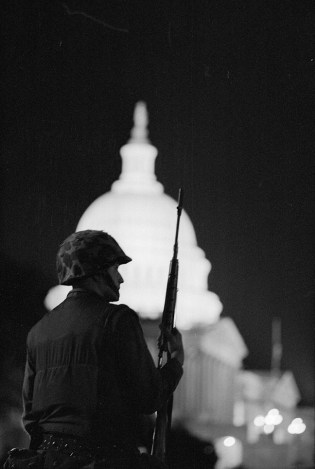

King was declared dead at 8:05 p.m. Eastern time. At 9:25 p.m., the first window shattered. It belonged to a Peoples Drug Store—part of a large DC chain—which had just closed its doors in accordance with the crowd’s demands. From there, the chaos metastasized. A 15-year-old boy broke into the Republic Theatre and emerged with a bag of popcorn. A Safeway supermarket up the street fell to looters, and then an appliance store. By midnight there were fires, first on 14th Street, and then in other black neighborhoods: 7th Street NW, H Street NE, and communities east of the Anacostia River. Violent clashes, fire bombings, and widespread property destruction rocked the city. Eventually, the Army and National Guard were called in and strict curfews were imposed. On April 6, order was partially restored, but by then, the damage was vast. When the dust finally settled, the toll stood at 13 dead, 1,201 injured, 7,640 arrested, 5,248 tear gas grenades launched, and more than $27 million in damage, or around $200 million in today’s dollars.

At the height of the bedlam, Gen. Ralph E. Haines Jr., the Army’s vice chief of staff, reported, “Most of 14th Street is gone.” Historian J. Samuel Walker takes that bleak assessment as the title of his new book, which explores the question that policymakers around the country were asking after the 1968 riots that rocked DC, Baltimore, Kansas City, and Chicago, and those the year before in Detroit, Newark, and other major metropolitan areas: Why did African American residents visit such destruction upon their cities?

But 50 years later, with racial inequality and police violence still rampant, the converse question might be more relevant: Why haven’t people similarly risen up in recent decades?

After all, Walker says in an interview, “the conditions in most cities are still there.”

Following the destruction of 1967, President Lyndon Johnson convened the Kerner Commission to assess its causes and solutions. The commission found that black frustration was prompted by discrimination, high rates of poverty and unemployment, police brutality, and inadequate schools and housing—all of which are still largely present today. The commission famously observed the country was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” Some of these issues may have diminished, but none have disappeared. Twenty years after the riots, as cities continued to struggle in their aftermath, former Sen. Fred Harris (D-Okla.) co-edited a retrospective on the commission, on which he’d served. In it, he asked, “If things are worse, why aren’t blacks rioting today? Nobody knows.”

“The best conclusion that people have come up with,” Walker says 30 years later, “is that we don’t know.”

Government officials hadn’t expected riots in Washington in 1968 either. Even after the destruction elsewhere in 1967, Walker writes, city leaders were hopeful that DC would avoid a similar fate because it enjoyed three distinct advantages: a sizable black middle class, a newly semi-autonomous local government headed by an African American mayor, and the fact that the city’s troubled “ghetto” areas were spread throughout the District rather than concentrated in one place where a single spark could set off a blaze of protest.

Obviously, these factors didn’t protect the city from riots, and now the shortcomings of the prophecy carry a renewed sense of portent. Political and economic progress don’t necessarily insulate a city from unrest; sometimes they might just serve to emphasize the gap that exists between a particular community’s circumstances and full equality.

Consider the question of high unemployment within some black communities and how it may contribute to social instability. The black unemployment rate was actually close to a historic low in 1968—it was higher last year, and it hit its highest levels on record in the early- to mid-1980s, when there were no major riots. Political representation? The 1960s riots came after Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act and black mayors took charge of major cities, and yet life failed to improve for many African Americans. Similarly, the recent black protest movements followed the recovery from the recession, which didn’t lift all socioeconomic groups equally. The election of the country’s first black president not only didn’t end racial discrimination and police brutality but prompted a backlash that swept Donald Trump into power.

Economic inequality has only widened since 1968. The wealth gap between black and white households has more than tripled in the past half century; the net worth of the average white family is now 10 times that of its black counterpart. The percentage of African Americans who are incarcerated has nearly tripled since 1968, going from 5.4 times the white rate to 6.4 times. The Kerner report stated, “To some Negroes, policemen have come to symbolize white power, white racism and white repression.” Many African Americans would argue that hasn’t changed.

In 1988, looking back on the riots 20 years earlier, Washington Post columnist William Raspberry wrote that African Americans had resorted to looting and destruction because they felt they had “nothing to lose.” Thirty years later, Trump used the same language on the campaign trail in remarks that were widely condemned as wrong and offensive. Trump’s depiction of majority-black city neighborhoods as urban hellscapes recalls Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign speeches about the “national disgrace” of “the disorders and the crime and violence that are now commonplace in Washington.” This rhetoric may appeal to some suburban voters who value law and order, but they’re extraordinarily frustrating to city residents. Walker quotes a DC schoolteacher who commented in 1963, “I keep reading that Washington is a jungle. We don’t consider it a jungle. It’s our home.”

Another reason DC was supposedly riot-proof was that poorer black neighborhoods were not concentrated in one area. It’s trickier to measure the changes on this front, but one thing is clear: The most prominent of the old so-called “ghettos” where the riots began in 1968 have been radically transformed. 14th Street NW has become the city’s epicenter of upscale restaurants and luxury apartments. 7th Street NW and H Street NE, which followed 14th in the spread of arson, have in recent years followed it in the spread of rapid gentrification. Some longtime Washingtonians are convinced it’s all part of a conspiracy known as “The Plan,” concocted by white residents to drive African Americans out of the city; others say it’s just due to the central location of these areas and the nationwide trend of inner-city revival. The neighborhoods east of the Anacostia, meanwhile, remain overwhelmingly black, and some are the poorest in the city.

Priced out of the city, low-income African Americans are increasingly moving to the suburbs, reflecting a broader trend across the country, where Americans in poverty are now more likely to live in the suburbs than the cities. (The Kerner Commission actually recommended moving African Americans out of the cities in order to promote integration, but the new pockets of concentrated poverty in the suburbs surely weren’t what the commissioners had in mind.) That’s one reason the most famous racial protest movement in recent years was born not in a major city but in Ferguson, Missouri, a St. Louis suburb that was 99 percent white in 1970 and majority-black by 2000. In the DC area, the number of poor people in the suburbs grew by two-thirds between 2000 and 2015.

“Police departments after the ’67 and ’68 riots made efforts to improve community relations, to hire more African American officers, and that helped—especially in larger cities,” says Walker. “A lot of the problems we’ve had recently are in smaller cities.”

But African Americans weren’t the only group in DC to feel persecuted by the police. In the early 1990s, the Latino population, which had swelled as people fled Central American conflict zones, complained of routine harassment by a force that had few Latino officers. When an African American officer shot a Salvadoran man in the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood in 1991, Latinos living nearby rose up in protest, and a major riot quickly began. Police cars were flipped and torched, and stores were looted. No one was killed, but the riots sent a similar message to the ones 23 years earlier: The city could ignore its racial and ethnic inequality only at its own peril.

If the underlying social and economic conditions that frustrated African Americans were an important factor in the riots of 1967 and 1968, each one was catalyzed by specific events. In the 1967 riots, the spark was police actions seen as racially hostile; in DC, Baltimore, Chicago, and New York, the King assassination was the tipping point. In fact, of the 10 costliest civil disorders in US history, as compiled by the Chicago Tribune, 9 were triggered by either the King assassination or police conflicts. (The Los Angeles riots of 1992 that occurred after officers were acquitted in the beating of Rodney King were the clear exception to the absence of widely destructive and lethal riots in recent decades, leaving more than 50 people dead and 2,000 injured.) Police brutality led to the death of Freddie Gray in 2015 and prompted Baltimore’s most violent episode since 1968. That one stayed under control—no one died during the police clashes—but the next one might not.

There’s an unfortunate Groundhog Day quality to the whole thing: After each riot, there’s plenty of soul-searching, but the racism and the inequality and the brutality persist, as the pressure continues to build until the next eruption. Kenneth Clark, a social scientist who appeared before the Kerner Commission after the 1967 clashes, recalled a riot half a century before that. “I read that report…of the 1919 riot in Chicago,” he told the commission, “and it is as if I were reading the report of the investigating committee on the Harlem riot of ’35, the report of the investigating committee on the Harlem riot of ’43, the report of the McCone Commission on the Watts riot.” It was, he said, “the same moving picture re-shown over and over again, the same analysis, the same recommendations, and the same inaction.”