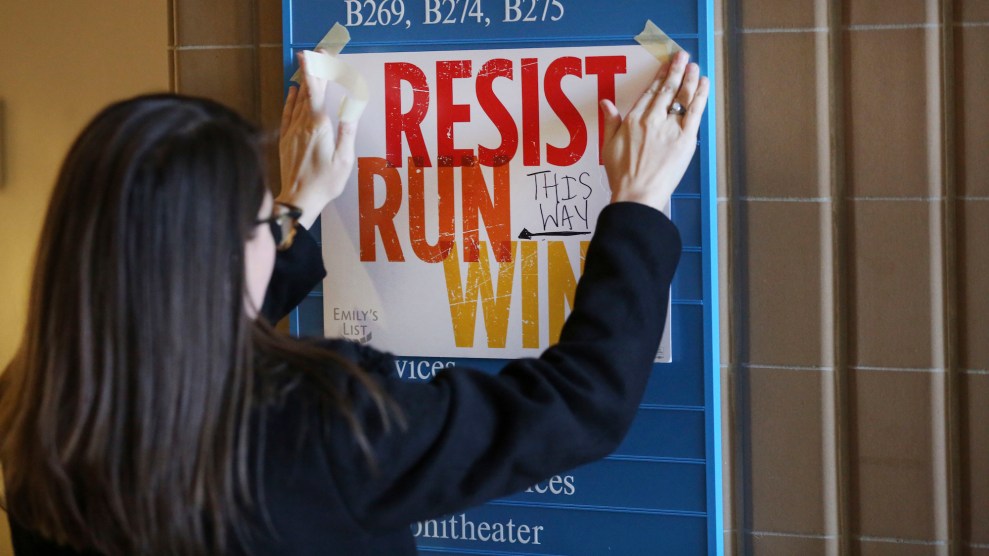

Lianna Stroster, the training director at EMILY's List, posts a sign directing to a women's candidate training workshop in Dallas on December 9, 2017.LM Otero/AP

In the days leading up to Maine’s June 12 primary, Maine Women Together, a Portland-based political action committee, launched a barrage of Facebook attacks on Adam Cote, a leading candidate running in the Democratic gubernatorial primary. Six ads, almost exclusively aimed at a female audience, called out Cote’s past as a self-identified Republican and lambasted him for a debate appearance in which he referred to his opponent’s gun control stance as “political theater.”

The ad campaign had cost nearly $200,000 dollars. And Maine Women Together hadn’t raised the money itself: It had been provided by Women Vote!, the independent expenditure arm of EMILY’s List, the national political group that aids pro-choice women candidates. Cote, a pro-choice candidate himself, decried the move as “outrageous” and called the “outside group” spending “unprecedented and exactly what people hate about politics.” Cote ultimately lost the Democratic nomination to the advertisement’s intended beneficiary: current Maine Attorney General Janet Mills.

Cote hasn’t been the only Democrat to attack EMILY’s List in 2018. David Min, who lost in the primary for California’s 45th District, slammed fellow Democrat and eventual primary winner Katie Porter in an advertisement for taking money from “Washington insiders.” In Pennsylvania’s 7th District primary, District Attorney John Morganelli, a staunch anti-abortion Democrat, took issue with the group after EMILY’s List spent $370,000 to boost the primary’s eventual winner, Susan Wild, stating that the organization had mischaracterized his record.

Ahead of Kansas’ August 7 primary, EMILY’s List has spent $400,000 on an ad campaign touting the credentials of Sharice Davids, a gay Native American activist, attorney, and former Obama White House fellow running for Congress in Kansas’ 3rd Congressional District. The ads drew ire from supporters of Brent Welder, a Bernie Sanders-backed Democratic candidate and Davids’ biggest challenge. When Sanders campaigned for his former delegate in July, he took a dig at Davids’ backers. “We don’t want to be supportive of candidates who simply raise money from the wealthy and then put 30-second ads on TV,” Sanders said.

A record number of women are seeking office this year, a momentous surge that’s left some male candidates wondering if being female is a political advantage in and of itself. The majority of this wave reflects the values that EMILY’s List desires in candidates—nearly 70 percent of the more than 2,600 women running for state or federal office are Democrats, a demographic likely to stand up for abortion rights. And EMILY’s List has been both a chief beneficiary and champion of the observed increase in women’s political engagement: More than 40,000 women have contacted EMILY’s List about running for office during the midterms, eager to tap into resources that not only include the half a billion dollars the group has raised for candidates over the course of its 33-year history, but also political advising and media buys.

The group’s imposing presence has led candidates on the receiving end of its political offensive to smear the group as a juggernaut wielding Washington-style influence. EMILY’s List and its endorsed candidates, meanwhile, assert that the group’s influence is still required to balance the playing field in a time when the number of women running is still a notable observation.

The origin story of EMILY’s List has become a well-trodden legend. Founder Ellen Malcolm, a former political press secretary, gathered 25 Rolodex-wielding women into her basement so they could inform their friends—mostly fellow women—about a new network that would raise money for pro-choice Democratic women candidates. That group eventually became EMILY’s List, named for the acronym “Early Money is Like Yeast.” The simile captured the group’s stated purpose: raise money for women candidates early in a race in order to attract other big donors later, which Malcolm identified as one of the chief barriers facing women candidates seeking office.

Those humble beginnings stand in sharp contrast to the organization’s influence more than three decades later. The membership-based organization’s initial group of 25 backers has now grown to more than 5 million. They’ve helped elect nearly a thousand women to political office, including 139 to Congress. With more than $47 million in the bank for direct candidate support and another almost $16 million at the ready for independent support or attack initiatives, it’s on pace to break its own fundraising records and ranks in the top five across all political action committees in donations this cycle. Malcolm’s own professional journey speaks to how much the organization has elevated women candidates: She served as co-chair of Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign.

2018 is hardly the first time EMILY’s List has been attacked for its influence. Almost every election since the 1990s has yielded news stories about the group’s increasing power, and that growing footprint has had its attendant number of critics. But in the past, those attacks have generally come from Republicans. Back in 2000, for example, Republican Mike Rogers—who went on to serve seven terms in Congress representing Michigan’s 8th District—slammed the group for running ads in his race, demanding his opponent, Democrat Dianne Byrum, “disavow” the attack.

But the criticism has been much more rampant this cycle, coming heavily from progressives and fellow Democrats who would have likely once championed the group’s efforts. In an election year that’s been defined not only by women candidates, but also women voters and volunteers, it’s easy to see why they’re irked—EMILY’s List-backed candidates have been, on the whole, winning, and the group’s attacks have been crippling to otherwise viable campaigns. The attack ads on Cote in Maine came at a crucial moment for a candidate attempting to position himself as a progressive who could attract women voters. Women Vote! dropped nearly a quarter of a million dollars to support Porter in California, an amount Min’s campaign couldn’t keep pace with. In Davids’ Kansas race, the EMILY’s List ad campaign cost twice more than what Davids had raised herself by that time.

Julie McClain Downey, senior director of campaign communications at EMILY’s List, finds the criticism unwarranted, a result of candidates “screaming foul” because they’re losing to women the group has backed. “The legacy of EMILY’s List is really what we’re seeing coming to fruition today,” she says of the successful bids. Press Secretary Alexandra De Luca attributes the rise in attacks not to increased animosity, but to the fact there are just more women running campaigns in 2018. “I think it stems from the sheer number of women running this cycle,” De Luca says. “It makes sense that this kind of opposition is coming.”

The vast number of women running has been particularly thorny in races where Democratic women face one another—when EMILY’s List has endorsed one pro-choice candidate over another. In Georgia’s Democratic gubernatorial primary, for example, candidate Stacey Evans took umbrage when the group endorsed her competitor and eventual Democratic nominee, Stacey Abrams, even though both candidates had been pro-choice. “If I were a donor, I would be very upset to know that my dollars were going to fight for one pro-choice woman against another,” Evans told the New York Times in May.

A recent article from the Intercept detailed similar criticisms, noting that EMILY’s List had failed to offer timely endorsements, or any at all, to women running for Congress in New York. But with a staff of only about 120 people and tens of thousands of women seeking EMILY’s List’s help—43 times the number who sought help in 2016—it’s inevitable that the organization would skip out on supporting some candidates. Every endorsement requires research into a nominee’s past and interviews with the candidates and their teams. Being able to prove a candidate’s viability without a national boost is key in that endorsement too, something a Splinter article from earlier this year noted through the story of Lucy Flores, a Nevada assemblywoman who EMILY’s List had passed on during her 2016 run for Congress because, the article suggests, Flores hadn’t raised as much money as her fellow Democratic female competitor. “EMILY’s List’s involvement was never a given,” a spokesperson for Davids’ campaign says. “We had to work really hard to show them that we were a viable candidacy.”

EMILY’s List’s Downey says she understood that hardship, one reason why she says the organization is still so critical to the candidates who seek it out. “If this was easy, we wouldn’t need to exist,” Downey says. “It is harder for women to run successful campaigns.” Gina Ortiz Jones, the Democratic nominee for Texas’ 23rd Congressional District, argued much of the same when a Democratic competitor attacked her national endorsements during a February primary debate. “I’m proud of all of the support that I have received from organizations that want to help underrepresented communities,” Ortiz Jones said, taking a moment to specifically recognize EMILY’s List’s support.

Just over 19 percent of House members are women, as are 23 percent of US senators, and only six women currently sit in governor’s mansions. Kelly Dittmar, an assistant professor of political science at Rutgers University-Camden and a scholar at the Center for American Women and Politics, worries that much of the focus on women candidates and the support they’re getting will obscure the fact that women in politics are still the exception, not the rule. “In the effort to celebrate the increase in women candidates, we’ve forgotten to remind people that they’re still a minority of candidates—more men are running as well,” she explains, adding, “It’s so important to put that in context, so the story in November is not to talk about how women failed. We don’t want a narrative that discourages other people from running.”