A mishmash of state plans and existing laws doesn’t sound like much. Climate experts have long preferred a national, economy-wide approach to cutting carbon pollution. But existing and announced state plans would do more good than you might assume.

Ten northeastern states already run a functional cap-and-trade system, and 11 Western states and Canadian provinces are planning to start their own, the Western Climate Initiative, in 2012. And the Environmental Protection Agency continues its own march toward regulating climate pollution—which the Supreme Court directed it to do.

So it’s pretty darn useful that the World Resources Institute has a new report out today that calculates what exactly states and federal agencies could accomplish in the absence of Congressional action. The WRI research group looked at current and in-the-works state programs, as well as existing law directing federal agencies to cut carbon emissions. They measured the impact of these combined activities against President Obama’s pledge in Copenhagen last year to cut emissions “in the range of 17 percent” below 2005 levels by 2020.

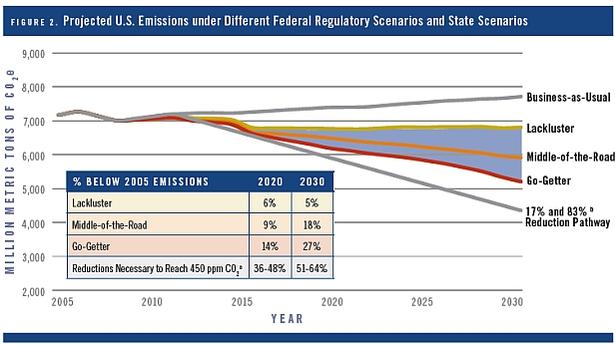

The top-line finding: States and federal agencies could keep us on track in the near-term—until about 2016—but after that they would be insufficient. That’s the best-case scenario. Because there’s so much uncertainty about how state and federal agency plans will be executed, WRI mapped out “lackluster,” “middle-of-the-road,” and “go-getter” scenarios.

Here’s how each would perform compared to business as usual: Courtesy WRI.org

Courtesy WRI.org

The bottom line on that graph charts the CO2 reductions the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says the whole world must achieve to avert catastrophic climate change. But even meeting those targets only gets us down to 450 parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide-equivalent in the atmosphere; scientific consensus holds that 350 ppm is the safe upper limit.

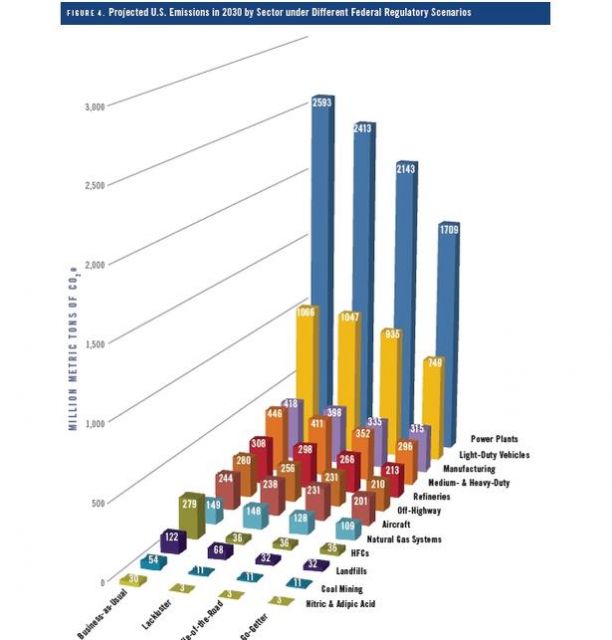

WRI also mapped out the projected emissions from different sectors of the economy based on the various scenarios: Courtesy WRI.org

Courtesy WRI.org

The electricity industry (in blue) is the biggest reduction target by far, and that’s where things get wonky quickly. The report considers regulatory action the EPA could take under several parts of the Clean Air Act—New Source Performance Standards, Best Available Control Technology, and even more obscure titles and section numbers. But none of this works if Congress strips the EPA’s authority to regulate climate pollution under the Clean Air Act—something some senators have threatened to do.

“The study highlights both the need to pass climate legislation and the importance of preserving existing authorities,” WRI President Jonathan Lash said in a prepared statement. “The study’s findings make it very clear that current efforts by Congress to curb EPA authority will undermine U.S. competitiveness in a clean energy world economy, block control of dangerous pollutants, and put the U.S. at odds with its allies.”

The report also looks at steps the energy and transportation departments could take to boost efficiency standards for appliances and automobiles. Notably, it does not measure transportation planning—which has a profound effect on oil consumption—or forestry or agriculture.

The authors also concede something that these sorts of reports tend to downplay: It’s hard to predict the future. “Longer-term reductions post-2020 are less certain under all analyzed scenarios,” they write, “primarily due to uncertainty about how quickly aging power plants will be replaced and the transportation sector can be transformed.”

Hence the focus on the next ten years. The report will no doubt meet criticism somewhere—in a hyper-partisan era, it’s easy to dismiss think-tank research as so much political ammunition. What’s interesting about this report is that it doesn’t make any claims about the amount of jobs created, money saved, double rainbows produced, etc. WRI makes it clear it wants a climate bill; here it looks at what may happen without one.

So is this any comfort? Good news or bad? The devil, as always, is in the details and the execution. The report illustrates the wide range between “lackluster” and “go-getter” policy. That’s the field of play for anyone who wants to help.

Update: Here’s an explanatory video from WRI:

This post was produced by Grist for the Climate Desk collaboration.