Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainees walk in September inside the Winn Correctional Center, a for-profit prison in Winnfield, Louisiana, operated by LaSalle Corrections.Gerald Herbert/AP

In August, Mother Jones reported that asylum seekers at a Louisiana jail were pepper-sprayed and beaten after protesting their indefinite detention. Now, following a damning inspection that confirmed the use of force, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has stopped using the jail.

The Bossier Parish Corrections Center stopped housing ICE detainees in the past few weeks, says Lt. Bill Davis of the Bossier Parish Sheriff’s Office. “ICE had been decreasing the number of detainees they were sending us for the last couple of months,” Davis says. “So they’ve decided they don’t need the facilities anymore.” ICE has been taking fewer people into custody in recent months, as border crossings have declined amid the Trump administration’s sharp crackdown on asylum seekers.

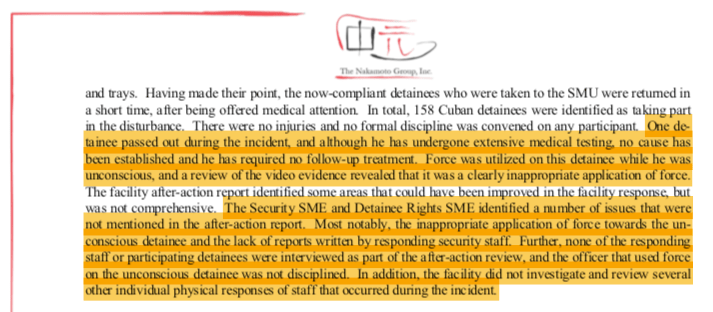

The Nakamoto Group, the company ICE pays to inspect detention centers, concluded in a December report that force was used against at least one detainee during the August protest. “Force was utilized on this detainee while he was unconscious,” the report states, “and a review of the video evidence revealed that it was a clearly inappropriate application of force.”

The company further faulted the facility for failing to include the incident in an after-action report. The officer who used force, the nature of which was not detailed in the inspection report, was not disciplined. The jail also failed to investigate several other unspecified “physical responses of staff” during the protest. The inspection, which has not been previously reported, was posted last month on ICE’s website.

An excerpt of the Nakamoto Group’s inspection.

An ICE spokesman did not respond to inquiries about whether the agency’s decision to stop using the jail was related to the problems identified by the Nakamoto Group. Louisiana attorneys had heard rumors that ICE planned to stop using the jail prior to the inspection. Across the country, the number of people detained by ICE has fallen from a record high of more than 55,000 to 39,983 at the start of the month, though that’s still about 5,000 more than at the end of the Obama administration.

The asylum seekers detained—and in some cases beaten or pepper-sprayed—at the Bossier jail had come to the United States exercising their legal right to seek protection from persecution. Instead of releasing asylum seekers while they await court hearings, as has been the case in the past, the Trump administration has subjected most of them to indefinite detention, often in jails that also hold convicted criminals.

The Nakamoto Group painted an unusually bleak picture of life inside the jail. Inspectors found that detainees at the Bossier jail were “inconsolable” about their situations. “They complained, almost unanimously, about the lack of information from the courts; lack of attention from ICE officers; and lack of knowledge regarding deportation status,” the report states.

Text messages provided to Mother Jones in August by attorney Lara Nochomovitz depicted a chaotic scene at the Bossier jail as Cuban detainees protested their indefinite detention. “There are lots of cops who came from another prison, they beat up the Cubans, they pepper-spray them and handcuff them,” one of the detainees wrote in Spanish. “There’s even an ambulance here. Help us please this is ugly!”

At the time, Davis called the incident a “small disturbance” that began when about 30 people started yelling at a lunch table. Davis said that although they didn’t get physically violent, deputies used pepper spray to “deescalate” the situation. He said that one of the detainees had to be transported to a local hospital “for anxiety attack issues” but denied that anyone was beaten.

Nakamoto Group inspectors determined that 158 Cubans participated in the protest—far more than was previously disclosed—and that a “chemical agent” was used against them. The report states that, at “a minimum,” a proper investigation of the incident should have established “review teams” that included ICE staff and health care workers at the jail, not just the jail’s security staff. According to the report, those teams should have taken statements from everyone involved, reviewed video footage, and collected all other available evidence. “Every physical response that went beyond the routine application of restraints should have been investigated individually,” the report states. “Staff that were determined to have applied either unjustified or excessive force should have been disciplined and re-trained.” None of that apparently happened.

The Nakamoto Group faulted ICE for failing to monitor conditions. Inspectors found that ICE officers were not conducting the weekly visits required by the agency’s detention standards. During one two-month period, inspectors were unable to find evidence of any ICE visits. The report recommended that ICE conduct announced and unannounced visits to monitor conditions and speak with detainees. The ICE spokesman did not respond to inquiries about whether those visits occurred.

In a January 2019 inspection, the Nakamoto Group identified 122 deficiencies at the Bossier jail, compared to an average of 11 at the other ICE detention centers it inspected last year. In December, it found 50. Despite the deficiencies, the facility indicated to inspectors that it had not been fined by ICE for non-compliance. Last year, the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General found that ICE routinely fails to hold noncompliant detention centers accountable through financial penalties.

The same DHS report criticized the Nakamoto Group, finding that the company’s inspections “do not fully examine actual conditions or identify all compliance deficiencies” and that its inspectors “are not always thorough.” Independent investigations have come to similar conclusions. Scott Shuchart, who spent eight years at DHS’s Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, told the Project on Government Oversight, “Nakamoto has no credibility because of the volume of problems it has failed to uncover at multiple facilities over multiple years…It is a checklist driven, superficial inspection process.” In light of the company’s track record of underreporting deficiencies, the Bossier inspection report is all the more striking.

The Bossier jail is located in Plain Dealing, about 30 miles north of Shreveport, and held about 260 immigration detainees on an average day last year. ICE started using the jail in June 2018 and began using seven for-profit detention centers in Louisiana in 2019. Nochomovitz says most of her Bossier clients have been transferred to River Correctional Center, one of the new for-profit jails. She says that while conditions appeared to be improving at Bossier, her clients are much happier at River. “It’s still jail,” she adds.

ICE paid local authorities more than $60 per night for each person housed at the Bossier jail, more than twice the rate the state of Louisiana pays for criminal detainees. Julian Whittington, the Bossier Parish sheriff, made no secret of the fact that money played a role in his decision to move out more than 180 prisoners to make room for ICE detainees.

In May, before the protest, Davis dismissed the political controversies over immigration. “We don’t care about that,” he said. “Our job is to house inmates…whether they’re ICE inmates, or whether they’re parish or state, we’re housing them. That’s it.” He called the jail a “top-notch correctional facility.”