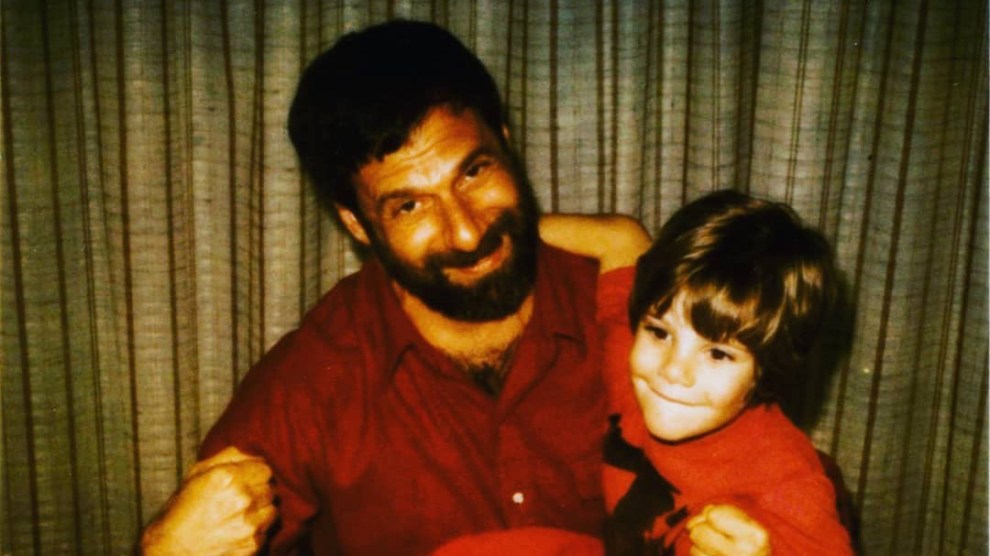

Chesa Boudin as a boy with his dad, David GilbertCourtesy of Chesa Boudin

San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin was at home cooking on Saturday afternoon when his dad, David Gilbert, called from a prison in upstate New York. Boudin was glad to hear his father’s voice. But he was worried about his old man: Someone in the cell next to him had tested positive for the coronavirus.

At 75, Gilbert is one of the oldest prisoners in the state. Even calling his son is risky for him now, since hundreds of guys at Shawangunk Correctional Facility share the same phones to call home. Before dialing his son, Gilbert wrapped the receiver with an undershirt to avoid touching it to his face. He would hand-wash the shirt after returning to his cell.

As the coronavirus sweeps through the country’s prisons and jails, Gilbert is one of the tens of thousands of elderly inmates at high risk for complications. In New York, about 2,600 prisoners were at least 60 years old in 2018. A greater number have other serious underlying conditions. Now Gilbert is part of a group of vulnerable inmates petitioning a court to protect them from the deadly virus by releasing them early.

In 1981, when Boudin was just 14 months old, his mother, Kathy Boudin, and Gilbert—both members of the leftist Weather Underground group—were arrested for serving as getaway drivers during the notorious Brinks heist, which resulted in the deaths of a company guard and two police officers. Boudin was raised in Chicago by his parents’ professor friends, fellow Weathermen Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn. He got to know his own mother and father through phone calls. They liked to tell him fictional adventure stories—Gilbert calling to share a chapter one day, and Kathy Boudin following up later with another. She was paroled in 2003, the year Boudin became a Rhodes Scholar. Gilbert received a longer sentence and has many years left in prison. Boudin visited him last November, on the same day he learned he had been elected as San Francisco’s DA.

Since then, the coronavirus has sickened at least 20 incarcerated people at Shawangunk, and 414 in other New York state prisons. Fifteen inmates have died. Nationally, the percentage of people in state prisons who are 55 and older more than tripled between 2000 and 2016, to 150,000 people, according to a recent Marshall Project analysis, which noted that for the first time ever, these older adults compose a greater percentage of the prison population than people between the ages of 18 and 24.

Gilbert is trying to be careful: He’s skipping some meals to avoid the crowded mess hall, and forgoing breaks outside and exercise in the yard. But his cell has a wall of bars that open onto a pathway, so he’s regularly within six feet of other people. “We’re really worried about him,” says Boudin, who notes that his dad has underlying medical problems, including hypothyroid disorder and damage to his digestive system, that have been exacerbated by the decades he’s spent in prison.

And the prison, Boudin argues, cannot keep his father safe. Social distancing is virtually impossible behind bars, and protective equipment and tests are in short supply. Because of this, many states have started releasing some people early, especially those who committed nonviolent crimes, are almost done with their sentences, and have medical conditions that put them at greater risk of complications.

But New York, an epicenter of the virus, has been relatively slow to let them go. Gov. Andrew Cuomo has resisted using his clemency powers to release people, leaving stacks of applications—including Gilbert’s—pending. The state has only freed 162 inmates, less than half of 1 percent of its prison population, in response to the pandemic. All of them were 55 and older and convicted of nonviolent crimes, with less than 90 days remaining on their sentence. By comparison, California, where Boudin is based, has let 3,500 prisoners go home early in response to the pandemic, or nearly 3 percent of its total prison population.

Gilbert and 21 other people in Ulster County prisons filed a habeas corpus petition for release on Monday with help from the Legal Aid Society of New York. The inmates argue their continued imprisonment during the pandemic, in facilities where they are at substantially higher risk of infection, violates the Eighth Amendment. “By design and operation, New York state prisons make it impossible for [them] to engage in the necessary hygiene, cleaning, and social distancing measures that experts implore all of us to take to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 transmission,” their petition states. Infrequent testing in New York prisons means the infection rate is likely much higher than has been reported. “In the absence of executive action by Governor Cuomo, courts must act to protect our clients’ constitutional rights to be protected from cruel and unusual punishment,” says Lauren Jones, their attorney.

Some of the prisoners who filed the petition are elderly and have served decades in prison; others have weakened immune systems from medication, cancer, or HIV, or struggle to breathe because of asthma, emphysema, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. One of the petitioners, Julio Rivera, reports that when he goes to his prison’s medical clinic to get insulin for his diabetes, he often encounters 20 or 30 other people there, and must stand closer than six feet next to some of them in line.

Another petitioner, Robert Drach, says that the medical unit where he receives chemotherapy also houses men who tested positive for COVID-19. Their family members worry they may not make it out of prison alive. “They deserve to get a second chance,” says Geannie Chalk, whose brother Richard Lee Chalk, 61, another petitioner, has atrial fibrillation, diabetes, asthma, hypertension, and sleep apnea. “There are nights my wife and I cannot even close our eyes” to sleep, says Roy Williams Sr., whose son Roy, 47, takes an immunosuppressive drug three times a day to treat his Crohn’s disease at Eastern prison, where 17 people have tested positive for COVID-19.

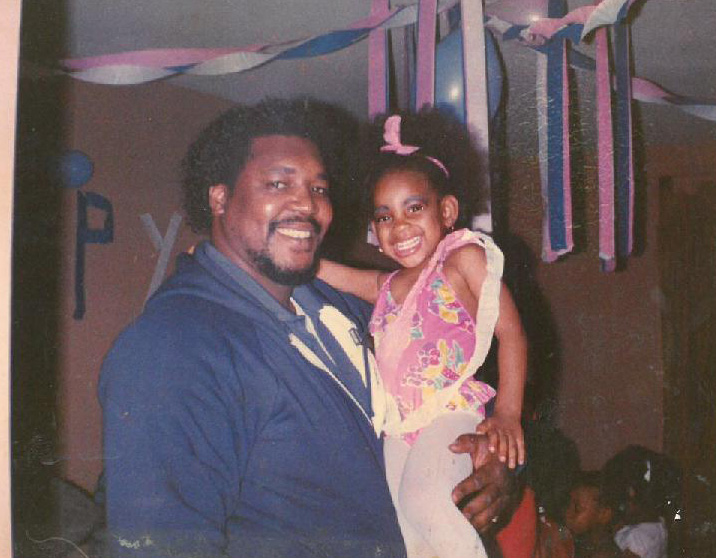

Courtesy of Legal Aid Society

Gilbert and the other men in the petition argue they are not a public safety risk, and that continuing to lock them up is unnecessary during the pandemic. New York’s Department of Corrections and Community Supervision declined to comment on the pending litigation.

In the nearly 40 years that Gilbert has spent in prison, he has never once received a disciplinary infraction, according to his attorneys. And during that time, he has become a mentor to younger incarcerated men. Jerome Wright, a civil rights activist, first met Gilbert at Great Meadow Correctional Facility in the 1980s. The two men worked together to develop peer education classes in prison about the AIDS epidemic. “I was much younger than him, in my 20s, and he was instrumental in quelling a lot of fear that the younger guys had about the prevalence of HIV infection, how you got it, and the conspiracy theories,” Wright recalls. “He would talk to us about what we could do to protect ourselves and our family. Because of his calm, quiet way of talking and the celebrity he had in the fight for justice for Black and brown people, we would listen to him. He was one of the mentors that helped me develop as a young man.”

Boudin says his father has also influenced how he approaches his job as district attorney. When Boudin campaigned last year for office, after years working as a public defender, he made national headlines by pledging to request prison sentences only as a last resort—an unusual stance for a prosecutor. During the pandemic, he has tried to find alternatives to jail for people who are older or medically vulnerable. And he helped reduce San Francisco’s jail population by 40 percent since January. Crime has dropped too, and the infection rate in the city’s jails has remained relatively low, even with widespread testing: Three inmates have tested positive so far (all three during intake). In jails in Chicago and New York City, by comparison, hundreds have been sickened by the virus. Boudin hopes to convince Gov. Gavin Newsom to enact statewide policy changes that could help release more elderly and medically vulnerable people from prisons during the pandemic.

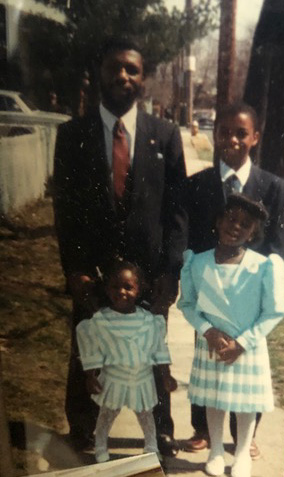

Courtesy of Legal Aid Society

Boudin tends to condemn his parents’ crime. “There are three families that don’t have a father anymore because of the crime that my parents participated in,” he told NPR’s Terry Gross recently. (Gilbert was not armed during the Brinks heist and did not attack anyone, but received a 75-year-to-life sentence under New York’s felony murder law.) As a district attorney, Boudin also emphasizes that public safety is his top goal. But his father and the other aging, sick prisoners in Ulster County have long since rehabilitated, he says, and keeping them in prison needlessly puts them at risk of death without any benefit to the broader community. “They are not a public safety risk,” he says. “They have all served long prison terms—they’ve changed, they’ve grown old.”

Research shows that, overwhelmingly, people usually age out of crime: One study of New York prisoners who were 65 or older found that only 4 percent were convicted of another crime after their release, compared to 16 percent of men younger than 50. Studies in other states have shown even lower recidivism rates for the elderly.

His dad continues to call regularly with updates. It’s a strange feeling, fielding the calls from New York during breaks from his own work to get people out of San Francisco’s jails. “I grew up feeling largely powerless to help my father,” Boudin tells me. “And now I’m district attorney, and I have a really concrete power and responsibility.” He pauses: “It’s an intense contrast, to have the responsibility and power to make these decisions with regard to so many people who are accused of crimes in San Francisco—and to be so powerless when it comes to my father.”