Anonymous

Position: Occupational therapist

As told to AJ Vicens

I chose to be in occupational therapy because I wanted to do something that helped people. I didn’t think I could stomach doing injections and the medical side, because I didn’t want to hurt people. I was more interested in the greater context of people’s lives than physical therapy, where they just work on the muscles. I really found a calling. It seemed like the most practical type of therapy you do. You’re addressing exactly what the person needs to be able to do in their life. Most of the time, I felt like I was making a difference.

When the coronavirus first arrived in America, and there were cases in my state, the management where I worked continued to act like it was overblown. Any kind of mitigating PPE was just going to scare everybody. They weren’t taking enough action to limit exposure and to protect people because it would cost them money.

One of my co-workers was wearing a mask, and nobody else was really wearing masks. It was sort of an optional thing. If you wanted to, you could, but they weren’t really distributing them. Some people started wearing them and literally one of the guys whose family owned the company was in the hallway in front of everybody else saying: “Why are you even wearing that? It’s not going to help anyway.”

Everybody’s scared. They’re talking of shutting down the state, and then to just have that kind of attitude so openly, and to just call her out in the middle of the hallway where everybody else could hear—that was the first time that I thought this is not going right.

We tried to voice concerns: “Why aren’t we tracking who’s going in and out of rooms? Why aren’t we limiting XYZ?” They were starting to talk about having us start going to some of the houses where some of our clients lived—and that would have exposed more people instead of less people.

It’s not like they were considering precautions beyond the economic price of taking those precautions. That just did not sit right with me from the beginning: They were going to expose us and expose the clients to continue to make money.

Everybody was very, very concerned. We were immediately considered essential workers. We were given a letter to carry with us in the car in case we were pulled over so that we could show that we were essential workers.

Anytime we voiced concerns about how things were being handled, we were told: “Just be happy you have a job. Everybody else is losing their job, just be happy you have a job.” But in our minds, we didn’t feel protected.

It was like it was a constant state of processing. You couldn’t catch up. You couldn’t catch your breath. You couldn’t feel like you had something under control, that you felt like you were facing the day prepared.

Instead, it always felt like, “What’s this new fresh hell I’m going to experience today? What am I not going to feel like I’m safe doing? What am I going to feel like I’m not safe for other people?”

I felt like I was potentially exposing other people. The clients essentially lived in this nursing home where they’re not going in and out of the building. But we were, and then anyone I had contact with outside of work.

My family—that was where I felt scared. Very scared.

I didn’t want to go to work. Every day felt like I was preparing for combat. Soon they started to institute the PPE. We started with a mask and an N95, and then we had to put a surgical mask over the N95 because the N95 is not supposed to be used repeatedly. So in order to keep it fresh and clean, we had to put the surgical mask over, and then we had a face shield over that, and then we had a gown added on top of that. It was so hot.

Every day you’re physically uncomfortable You’re doing a physical job rehabilitating people. I’m moving people, showering people, dressing people, changing people, transferring people, doing therapy.

But in addition, you’re doing other people’s jobs because other people started phoning it in or quitting, so then we all had to pick up the slack. So I was physically exhausted, mentally exhausted, and terrified all the time.

I felt like every day, I was failing someone, like I wasn’t meeting expectations. I wasn’t able to do my job. I was trying to do so many other people’s jobs just to care for these people who were trapped.

I felt like I was losing sight of what my job actually was. Eventually, once people started quitting, they needed us to pick up the slack and do extra work. But it was so mismanaged that the people who cared did the lion’s share of the work and just got so drained and exhausted, on top of already feeling disillusioned. Every day felt surreal, like you were in some kind of nightmare that was never going to end. And then they would have a meeting to discuss new cases and new protocols, and if people were going to and from the hospital, how they were going to deal with that. I just felt like I was in a nightmare.

Once things were starting to shut down, I started to be afraid. We pulled our kids from daycare, and the schools shut down. That was like: “Okay, the schools are shutting down, that’s a big sign that this is not going away anytime soon. And this is not good. This is a real serious problem.”

The tipping point for me was in the very beginning, before they instituted the PPE. I worked with a client without a mask in his room. This person had not been out of his room for months, because he’d been on bed rest. I ended up learning that within that week he died of COVID. This was in March, when people weren’t aware of how it spread so easily and that you could be a silent carrier. I was so terrified. And my employer told me, “You can just come back to work as long as you don’t have symptoms.”

I was appalled that they wouldn’t take it more seriously: quarantine the people who have been exposed to him without PPE; don’t bring those people back in to potentially expose it to other clients, very vulnerable people with tracheotomies, people on ventilators, and people whose health and immune systems were compromised. The bottom line wasn’t taking it more seriously and protecting people. The bottom line was, “How do we stay a viable business?”

After he died, I started calling everybody I could. I called the state health department, the county health department, I called my doctor. They all basically said the same thing: “Well, CDC guidelines say because you’re an essential worker, you can go back to work as long as you don’t have any symptoms.”

But that didn’t feel right to me. So I took the week off. Within the next day or two my youngest son, who’s 2, came down with a high fever and a headache and not feeling well. That’s when I started to really panic. I called his doctor and the health department again.

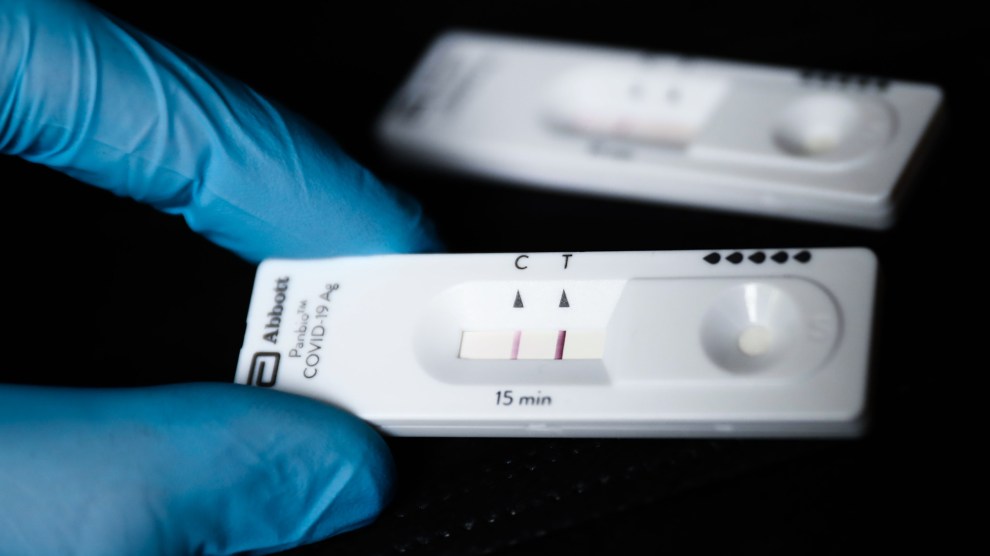

Nobody would test at that time. There was no testing available, so I just had to wait it out. Which was the scariest first 24 hours, and I wondered, “How is this going to go?”

They said it goes easily for children, and they get over it quickly. I started to backtrack in my mind: “Who did I have contact with? Who did I potentially have exposure to? Did I give this to my mother through some groceries I left on her porch? Did I give this to my aunt who is immunocompromised?”

I felt like I was the carrier because the kids hadn’t been out of the house for over two, three weeks at that point. So there was nobody going in and out of the house but me who had direct exposure to someone who died of COVID. I felt sheer panic. There were no answers.

Luckily the kids were OK, but both children ended up getting it. I don’t know if it was COVID because there were no tests available. But calling all these places they said to treat it as if it is, to quarantine them.

My employer was like, “Eh, come on back to work.”

That was when I realized it wasn’t about people, and they didn’t really care about their employees enough to handle this seriously. So that was the tipping point. And there was no recovery of trust after that.

I felt obligated to the people I worked with and the clients I served, to be there for them, and I felt obligated to my family to continue to provide an income. I was not given any option to get laid off, so if I was going to leave my job it was going to be that I quit. I started to feel like it was going to come to a boiling point. I was either going to have a breakdown at work and then not be able to recover from that and damage having a reference in the future. Or I was not going to be able to function anymore at home. I was going to continue to break down.

Everybody I was working with felt trapped and felt like they couldn’t leave their jobs. I was fortunate enough to go to my family and say: “I can’t handle this anymore. I don’t know what my options are. What if I quit? How will I be able to provide for my family? How will I be able to make the bills. If it comes to that point, will you help me?”

That was the first time I ever had to ask my family for money. I pride myself on being independent and being able to take care of myself and my family. So that was a really hard thing to do just for my own pride. But I had to. I had to know what my options were.

I never thought I would be in that position, especially because going into health care, everybody tells you: “Oh, that’s great. You know, you’ll get a job in no time—a secure job and you’ll never have to worry about being employed.”

I’ve been employed basically since I was 17. Being unemployed is new to me. And I wouldn’t have been able to take that leap without support from my family. That saddens me, too, because I know there are people trapped in really bad circumstances that they can’t leave because they don’t have the family support. I don’t regret leaving. I wish I would have been able to wait till I had another job lined up, but I wasn’t going to be able to function anymore.

It’s been my identity for the past 13 years. I’ve been an employee to this family-owned company, and they always talked about how it was one big family. They did do kind of special things for us. I felt for a long time that I was in this exceptional place that really cared about people. In the end, when push came to shove, it became not about that anymore. It just became about the money and the business, and that’s not why I went into health care.

I still am an occupational therapist, and I still have a license, and I’m going to go and continue to practice. But I do feel like a big part of my life is over. It’s sort of an identity crisis. Who am I now? I was grieving leaving the people I cared about, leaving clients I was dedicated to. I really cared about their progress and their rehabilitation, and that was just being pushed aside for the wrong reasons. In the end, I’m not going to die over my job. I’m not going to continue to risk my family for a job. You know, I had options, and other people don’t. And that’s very sad.