Click the highlighted text for more.

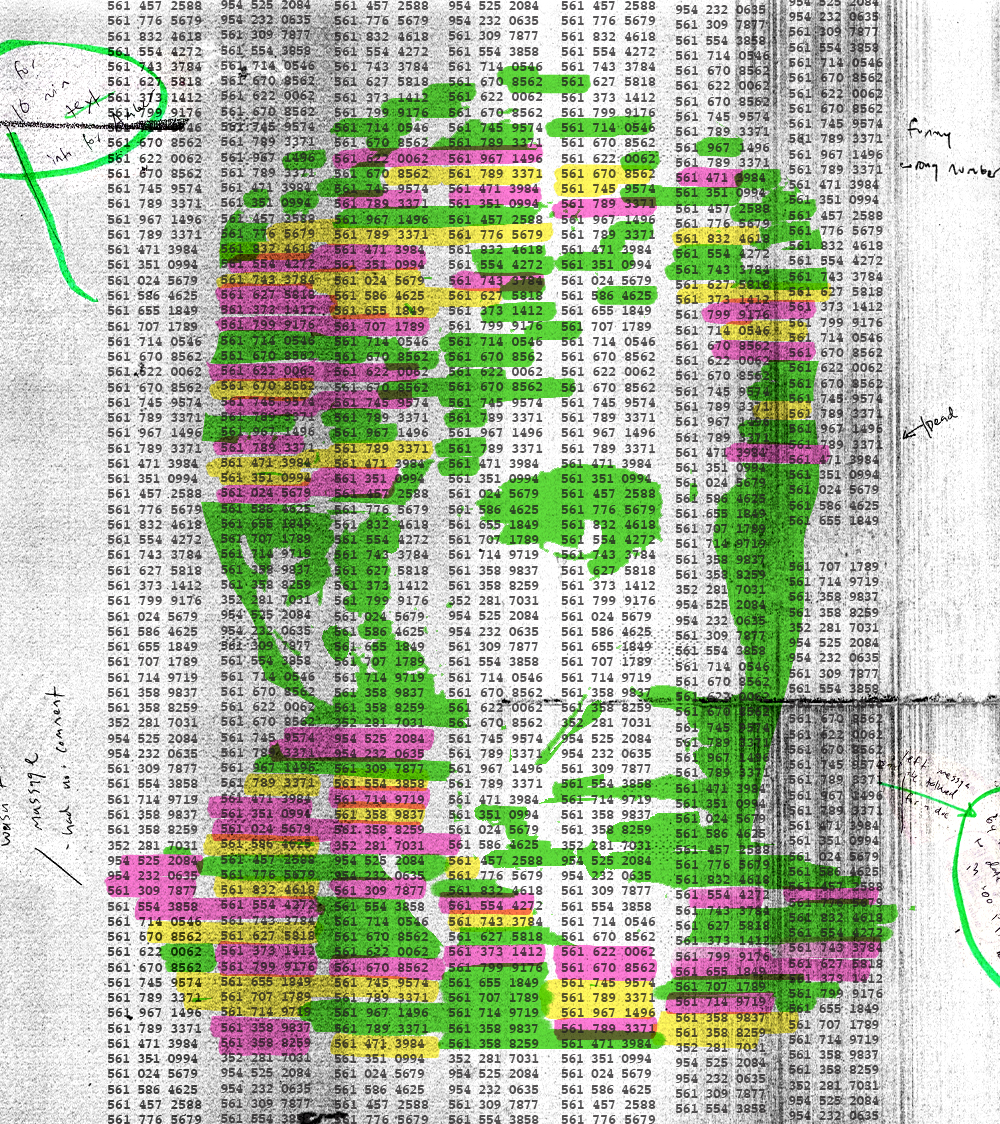

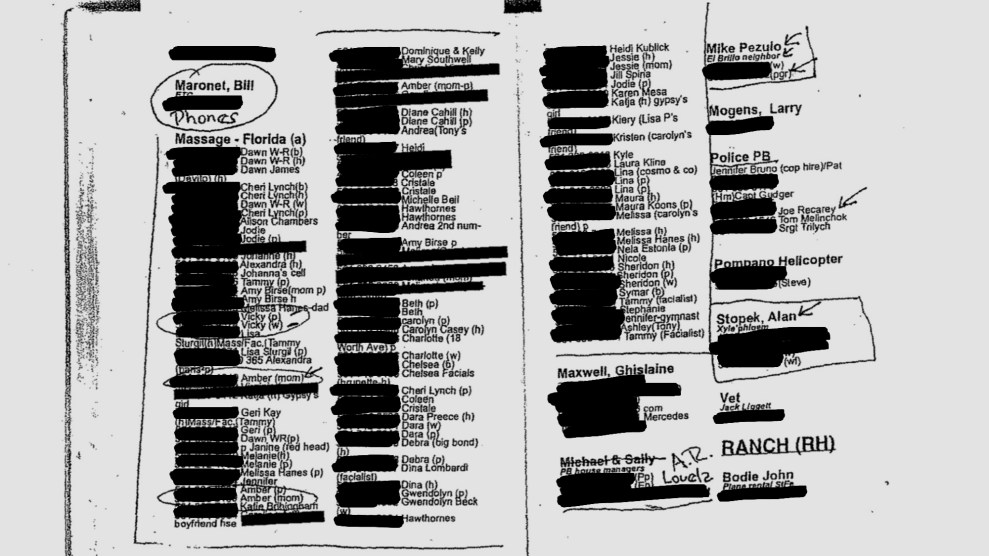

Jeffrey Epstein’s little black book is one of the most cursed documents ever compiled in this miserable, dying country. Totaling 97 pages and containing the names, numbers, and addresses of a considerable cross section of the global elite, Epstein’s personal contact book first turned up in a courtroom in 2009 after his former butler, Alfredo Rodriguez, tried to sell it to lawyers representing Epstein’s victims for $50,000. Rodriguez described the book, apparently assembled by Epstein’s employees, as the “Holy Grail.” It is annotated with cryptic marginalia—stars next to certain entries, arrows pointing toward others–and the names of at least 38 people are circled for reasons that aren’t totally clear. There are 1,571 names in all, with roughly 5,000 phone numbers and thousands of emails and home addresses. There are celebrities, princes and princesses, high-profile scientists, artists from all over the world, all alongside some of the world’s most powerful oligarchs and political leaders—people like Prince Andrew (circled), Ehud Barak (circled), Donald Trump (circled).

Rodriguez was Epstein’s butler at his Palm Beach mansion for many years. He was intimately familiar with his boss’s sexual proclivities. He claimed to have seen nude underage girls at Epstein’s pool, said that he would routinely wipe down and stow away sex toys in Epstein’s room after “massages,” and alleged that he saw child pornography on Epstein’s personal computer. In 2011, Rodriguez was sentenced to 18 months in prison for having tried to sell the book to an undercover agent after failing to notify investigators about its existence. Rodriguez said in court that the book was “insurance” against Epstein, who wanted him to “disappear.” Rodriguez died of mesothelioma shortly after serving his sentence.

The public first became aware of the book in 2015, when the now-defunct website Gawker published a version of Rodriguez’s copy, revealing for the first time just how ludicrously connected Epstein was to the people who run the world. Gawker’s file showed only names; attached phone numbers and emails were blacked out. Shortly before Epstein’s mysterious death in August 2019 in his cell at the Manhattan Correctional Facility, an unredacted version of the book popped up on some dark corners of the internet, with almost every phone number, email, and home address entirely visible, and I got my hands on a copy.

Epstein’s little black book isn’t little at all—it’s gargantuan. Its defining feature is its size and thoroughness, and there are just as many boring numbers as exciting ones–for every Jordanian princess there are three reflexologists from Boca. The listings are at times preposterously detailed, often containing additional names and numbers for people’s emergency contacts, their parents, their siblings, their friends, even their children, all alongside hundreds of car phones, yacht phones, guest houses, and private office lines. Some individuals have dozens of numbers and addresses listed, while others list just a single number and first name. Epstein collected people, and if you ever had any interaction with him or Ghislaine Maxwell, his onetime girlfriend and alleged accomplice, you more than likely ended up in this book, and then several years later you received a call from me.

I made close to 2,000 phone calls total. I spoke to billionaires, CEOs, bankers, models, celebrities, scientists, a Kennedy, and some of Epstein’s closest friends and confidants. I sat on my couch and phoned up royalty, spoke to ambassadors, irritated a senior adviser at Blackstone, and left squeaky voicemails for what must constitute a considerable percentage of the world oligarchy. At times the book felt like a dark palantir, giving me glimpses of dreadful, haunted dimensions that my soft, gentle, animal being was never supposed to encounter. At other times it was nearly the opposite, almost grotesquely boring and routine. Seeing at close range the mundanity of Epstein and his fellow elites–how simple and childish they could be–was a sickening experience of its own. The worst call by far was with a woman who told me she’d been groped by Epstein, an incident she said she didn’t report at the time out of fear of retribution from Epstein. (I have been aggressively counseled to remind the readers of Mother Jones that an appearance in the address book is not evidence of any crime, or of complicity in any crime, or of knowledge of any crime.)

They weren’t all elites, thankfully. Sometimes I would have delightful conversations with normal people who had cleaned a car or given Epstein a facial, and only shared in my distaste for Epstein and his circle. Sometimes I would call a number that had changed hands at some point since the book was compiled, and instead of reaching the governor or fashion designer I was looking for, I would end up with just a normal bloke on the line, some poor recipient of a torrent of wrong-number phone calls of the worst variety imaginable. Their fate was a twisted inversion of my own: The oligarchy wouldn’t stop calling them.

“Yeah man, people keep calling me up, asking for Muffie, and I’m like, you know, I’m just always polite, man.” That’s Elijah Hutch, 22-year-old aspiring music producer who lives in Flatbush in Brooklyn. He has the old cell number for Muffie Potter, wife of world-famous plastic surgeon Sherrel Aston and the fourth-greatest socialite in history, according to Town and Country magazine.

“They’ll text me about some dinner I went to, or how it was great seeing me with so and so, and I’m always just respectful man and just let them know, ‘Hey, man, I think Muffie gave you the wrong number.’” Eli had no idea who Muffie was, or Epstein for that matter, and I almost didn’t want to explain it to him, but I did: the child sex ring, the princes, the presidents, the suicide, the black book–everything. Out of all the people I spoke to, Eli had by far the most cogent analysis of the situation.

“Damn, man, this is all sounding so strange.” Find Eli Hutch on SoundCloud here. Let the haunting lyrics of “Go Away” give you strength as they did me, awake at my desk at 4 a.m. so I could call every pedophile in London.

My demons creeping, getting close, they just want to snatch my soul, but I won’t let them get a hold

What a world, any phone can reach any other. It’s almost unbelievable what a string of seven to 12 numbers can get you. All I did for weeks was sit on my couch, feel like dogshit, flip through this haunted book, and call people up one by one in between bouts of stress diarrhea. That’s it. You just type the numbers in, and sometimes you get a ring, and sometimes a person picks up.

THE FUZZ (MAYBE)

I made the first call from a coffee shop in Los Angeles’ Koreatown the day after Epstein’s suspicious suicide in his cell at Manhattan’s Metropolitan Correctional Center while awaiting trial, a convenient turn of events for the rich and famous people who would now avoid exposure in court. The death was a national scandal. Followers of the Epstein case—I’m including myself here—reacted to his death with a burst of paranoia and anger. Conspiracizing was rampant. I had come across a screenshot of an unredacted section of the black book and determined to track down its source. I decided to check the most awful place on the internet, 8chan, where I was quickly rewarded for my intuition—an unredacted PDF of the entire book had been posted just a few hours earlier. About 12 seconds later I was dialing Melania Trump’s personal cell phone. Voicemail. Then I sent a text to David Copperfield. “David, we need to talk. It’s about Jeffrey.”

I tried a couple more people, none of whom picked up, whereupon I was interrupted by a call from a restricted number. The guy on the line said he was with the FBI. He said there were “reports of fraudulent phone calls” being made on this line, which I immediately understood as bullshit—I wasn’t committing any phone crime or trying to trick someone into doing so. “I don’t know about fraudulent, but I have a feeling I know what you’re talking about,” I said, undoubtedly sounding cool, relaxed, unbothered. He then said, “I have a real call coming in,” to what sounded like someone else in the room, his voice quiet in the way of someone who has just pulled the phone off his face to look at it. He hung up and never called again, as far as I know. Whether the guy was FBI or a private security goon posing as a fed, the call was an important development—it told me that the book I was dealing with and the numbers it contained were genuine. Every cell phone, every yacht line, every private office number—they were all real, and every one of them was about to get a call from me.

THE ART-COLLECTING SCIENTIST DILETTANTE: “YOU’RE SO FULL OF SHIT.”

The next day I began calling en masse. By now, in an effort to spare my girlfriend any psychic harm, I was operating from the Los Angeles Central Library, first from a foyer, my voice bouncing off the high marble ceilings with embarrassing levels of clarity and volume, and then from a corner of the library’s art gallery, deftly maneuvering around any guests when necessary. That day had been terrible, full of wrong and disconnected numbers, and I was close to quitting the entire project out of both fear and hopelessness when I placed what was maybe my 50th phone call, to Stuart Pivar, who answered the phone and told me, “Jeffrey Epstein was my best pal for decades.”

Pivar, 90 years old, is an art collector, scientist, and a founder (alongside Andy Warhol) of the New York Academy of Art. He ended up speaking with me for over an hour about his “very, very sick” friend in a conversation we wound up publishing in its entirety. Stuart told me—over and over again—that Epstein suffered from “satyriasis,” which he described as the male version of nymphomania, and that he used his money and power to “make an industry” out of having sex with underage girls. This apparently entailed Epstein having sex with “three girls a day” and “hundreds and hundreds” in total. He said he never knew Epstein was having sex with children until Maria Farmer, a student at the academy and an acquaintance of Pivar, had told him she had been assaulted and held hostage by Epstein. He also claimed that Epstein had never invited him to what he called “The Isle of Babes,” a reference to Epstein’s private island where much of the child sex trafficking allegedly occurred.

Pivar said he was “in mourning” for Epstein, who had died just two days before we spoke. By turns morose, defeated, and indignant, veering between florid ruminations about teenage sexuality and bitter denunciations of me and my life choices, he unloaded his thoughts and feelings about Maxwell and Leslie Wexner, Epstein’s billionaire patron, as well as about the nature of perversion, criminality, perhaps even life itself.

On pathology: “What’s a pervert? There are all kinds of behavioristic aberrations, obviously, including mass murderers. You don’t call mass murderers ‘perverts,’ do you?”

On nature and civilization: “And so, all kinds of rules get made. And nature is not allowed to take its course on account of civilization. Jeffrey broke those rules, big time. But what he was pursuing was the kind of, I suppose, sexual urges which would—why am I telling you this stuff for? Leave me alone. Go away.”

On Epstein accuser Virginia Giuffre and Epstein’s child-sex ring: “Anyone who did one thing, let us say, to some 16-year-old trollop who would come to his house time after time after time and then afterwards bitch about it—why, no one would pay attention. Except Jeffrey made an industry out of it.”

On nature and civilization, cont’d: “The business of sexual attraction, the attraction of males and females in its natural state, is not the same as what happens when civilization puts [up] all kinds of rules. Because sexual attraction starts at a very, very young age. When I was 14, I had to deal with a girl who was only 13. And somehow, I remember, it was at summer camp. And I stopped having to do with her because of the tremendous age gap.”

On me and my life choices: “You’re so full of shit, it’s terrible. You should not be writing about this. You’re not qualified.”

On himself and his life choices: “Why did I talk to you! I’m a dead fish, and you’re going to ruin me. Luckily, I don’t know anybody who reads the Mother Jones anymore. I can’t believe it still existed.”

On my having inveigled him, so to speak, into yapping pointlessly: “You inveigled me, so to speak, into yapping pointlessly because I have nothing else to do for the moment, and I’m relying on you to understand what I say. If you misquote me or anything like that, I will sue your magazine until the end of the Earth….Tell me your name again so I can start writing a complaint to sue you.”

Somewhere in all this, Pivar managed to tell me the entire backstory of his decadeslong friendship with Epstein. Pivar had met Epstein through the New York Academy of Art, where Epstein was a board member. It was at an NYAA function where he met a young Maria Farmer, who along with her younger sister would become one of Epstein’s earliest accusers. Farmer, a painter, was at the Wexner mansion at Epstein’s invitation for what she believed was an art residency when, she alleges, Epstein and Maxwell sexually assaulted her and held her hostage for 12 hours with the aid of Wexner’s massive security team. After the ordeal, Farmer soon learned that her younger sister had also been assaulted by Epstein and Maxwell during a similar “artist residency.” Pivar told me he ran into Farmer at a flea market where she told him “this bizarre story…and I realized oh my god something was happening after years and years, which he”—Epstein—”didn’t tell me.”

My hourlong conversation with Pivar was genuinely illuminating. Pivar spoke about Epstein in the exact way many of his friends and colleagues would speak about him to me in the coming weeks—reverence mixed with an acknowledgement of Epstein’s essential disingenuousness. Much has been made in the press of Epstein’s intelligence, mostly due to his vast wealth, the glowing adoration of his elite peers, and the long roster of high-profile scientists and thinkers with whom he surrounded himself. Pivar was the first person to peel back the curtain of Epstein’s reputation with intimate, firsthand knowledge of the man himself, and to counter the prevailing media narrative at the time.

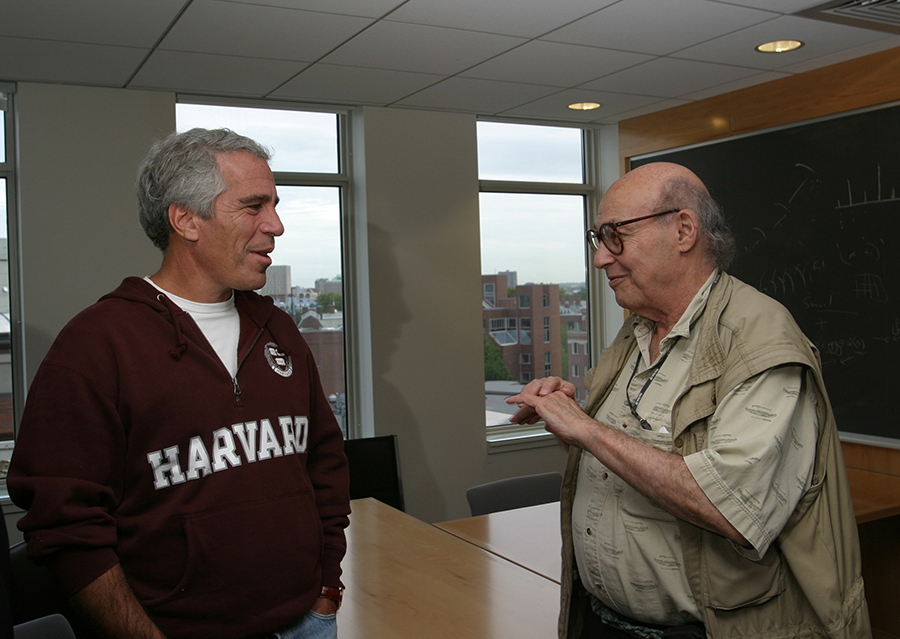

Jeffrey Epstein with the late Marvin Minsky, known as “the father of artificial intelligence.”

Rick Friedman/Corbis/Getty

Pivar had attended a few of the now widely publicized intellectual summits at Epstein’s house in New York. Epstein hosted dinner parties for world-famous scientists and thinkers from around the globe, people like Steve Pinker, Stephen J. Gould, Martin Nowak, Lawrence Kraus, and Marvin Minsky. “Jeffrey didn’t know anything about science,” Pivar said. “He would say, ‘Oh, what is gravity?’ Which of course is an unanswerable thing to present at a dinner to a bunch of scientists. And because he was Jeffrey, why, they would—and as the founder of the feast—they would listen to him and try to give [answers]. He was attempting, somehow, in his ignorant and scientifically naive state, to do something scientifically important. He had no compunctions about inviting people, and since he had money, they would listen.”

Epstein used his money and influence to brand himself an avant-garde intellect, a sparkling autodidact dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge on the far-out edge of human perception. In large part, it worked extraordinarily well. You could build mountains out of the bizarre, nebulous claims of esoteric knowledge ascribed to Epstein. “He was good at puzzles and finding things out. He could look at an organization and see what was wrong,” one friend told me. Wexner, when asked by Vanity Fair about his relationship with Epstein, said that he was good at “seeing patterns” in politics and financial markets. “Epstein’s mind goes through a cross section of descriptions,” Joe Pagano, a longtime friend of Epstein, has said. “He can go from mathematics to psychology to biology. He takes the smallest amount of information and gets the correct answer in the shortest period of time. That’s my definition of IQ.” Epstein’s attempt to portray himself as a galaxy-brain genius was surely helped along by his vast fortune—as I would find, the myth of his genius and the fortune were mutually reinforcing notions. His brilliance went largely unquestioned, because how else could he have been so rich? His wealth wasn’t so mysterious once you understood just how brilliant he was.

But Pivar didn’t buy it—at least not entirely. He still called his old friend a “very, very brilliant guy” and said Epstein had “a very—how should I say—charming way of expressing himself.” But Pivar also acknowledged that Epstein was a bullshitter. He “couldn’t concentrate on a subject for more than two minutes before having to change the subject, because he didn’t know what anyone was talking about and would blurt out the dumbest things,” Pivar said. In particular Epstein had an affinity for posing pseudo-deep questions like “What is up?” and “What is down?” at the scientific summits he hosted on his private island.

The act would wear thin eventually, Pivar recalled. “While everybody was watching, we began to realize he didn’t know what he was talking about. Then after a couple of minutes—Jeffrey had no attention span whatsoever—he would interrupt the conversation and change it and say things like, ‘What does that got to do with pussy?!’”

THE ACTRESS: “IT’S A WEIRD FEELING, I’M KIND OF REPULSED…”

Pivar was the first person I spoke to who had actually been close to Epstein. There would be others, and they would speak as freely and searchingly about Epstein as Pivar had, musing about their place in his life, some wracked with guilt, some clumsily rushing to his defense. By far the most eager sharer was an actress who had met Epstein in the early ’80s, before he’d gotten super-rich, and who maintained a decadeslong close friendship with him as he rose into the ranks of the elite. She asked that we not use her real name—we will be calling her Julie.

Julie’s name did not have any particularly special notation in the book. She’s not famous, by any means, and as far as I know she hasn’t ever talked to any other reporter or media outlet. “I like talking to you, I don’t really want to talk to anyone else,” she told me at one point. “How old are you? You’re like my therapist.”

Julie and I would speak multiple times on the phone over the months I worked on this story, sometimes for over an hour, sometimes for just a few minutes. She met Epstein in the 1980s at a dinner with her agent and a group of models at a known “model hangout” in New York City. Epstein approached the table and asked if any of them would like to go party at his apartment, and some of the women agreed, Julie included. While Epstein played the piano for the small crowd in his place, a friend of hers pulled her aside and told her, “I think he’s hitting on you.”

Julie allowed there was some initial mutual attraction and flirtatiousness, but nothing “crossed the line,” she said. The two were friends and remained friends and nothing more for their entire relationship. Soon after they met, Julie would find herself talking with people like Vera Wang and Andy Warhol at Epstein’s dining room table, or flying with Epstein on his private planes to meetings and parties around the world. She’d take a couple trips to his private island, Little Saint James; frequent his properties in New York, New Mexico, and Palm Beach; chill with a few of Bill Clinton’s staffers; and meet many of the people in Epstein’s inner circle, including Virginia Giuffre, his eventual accuser. “She was always there” in Little Saint James, Julie said.

Epstein’s home in Palm Beach, Florida.

Emily Michot/Miami Herald/TNS/ZUMA

Julie was always adamant with me that she never witnessed any sexual abuse during her entire relationship with Epstein, and that while she and everyone else knew that Epstein was into young girls, she never questioned whether any were of legal age. She also repeatedly told me how “happy” all the girls were to be with Epstein, at least the ones she saw. “The girls that complain and say they didn’t want to be there, or that they weren’t happy—if someone was unhappy, he had no time for you. His attention span was short and he could be really rude. So any girl that was around him had to be up and bubbly,” she said. “You know, he was always joking around, doing stupid, like, sexual jokes—if there was some girl walking around he’d pants her or something, you know what I mean? But it was always in jest….I let him go back then, but, you know, it’s a weird feeling. I’m kind of repulsed, but somewhere deep down I do miss that personality.”

Julie seemed absolutely helpless in the face of the monstrousness of the Epstein saga, and over the hours of calls we had she would achingly retrace her relationship with him and his circle with me. At times she was resolute in her condemnation, despairing over the seriousness of his crimes and at one point telling me she was “glad he’s dead.” At other times, even though she was a survivor of sexual assault as well, she would grow irritated and retreat into denial, offering sloppy, desperate defenses of Epstein’s actions or doubts about victims. She read me excerpts from her diary over the phone, shared gossip, and led me to flight logs and photographs to corroborate her story. She wept over how such an influential figure in her life, someone who treated her with kindness, someone whom she looked up to, could have done such awful, hideous things, and how terrible it was to look back on their relationship and feel betrayed, and worse still, to miss him. Although she had better insight into his life than perhaps most people on this Earth, she too had agonizing, unresolved questions, and parts of Epstein still remain an enigma even to her.

“I think a lot about why my role and some girls roles were different,” Julie told me. “I think Jeffrey liked to exploit people. If he saw a girl and could corrupt her, he might like that.”

There are two things that make Julie’s story unique. One, unlike many of Epstein’s friends, she is not a famous or known person. No reporter would know about her unless they did what I did and called every single person in the black book. Two, she knew Epstein well and from a very early point, being a part of what she called a small, core group of friends who remained in his life from before he was the rich and infamous figure the public knows him as today. From up close, Julie says, she watched his personality change as his riches and connections grew.

Throughout the many years of their friendship, she attended several private gatherings where only a small number of Epstein’s friends were present, giving her an opportunity to meet and get to know the big players in his life. When Julie first met Epstein he was wealthy but far from the ultrarich guy he would become. He was secretive about his work, always, but she believed he was working as a “bounty hunter” when they met, helping track down embezzlers for corporations (and possibly governments).

She told me she sat in on a meeting in Paris between Epstein and Leslie Wexner, the founder of L Brands and Victoria’s Secret who says Epstein embezzled at least $46 million from him. This was early in Epstein and Wexner’s relationship, not long after the two had been introduced by insurance tycoon Robert Meister. Epstein began working for Wexner in the late 1980s, though the nature of that work still isn’t entirely clear. Vanity Fair in 2003 said it was “related to cleaning up, tightening budgets, and efficiencies.” Julie told me Epstein was helping to track down employees who Wexner believed were “stealing” money from him at L Brands headquarters. “Leslie had said to him: ‘I have a problem in my company—there’s something wrong, someone is stealing from me. Would you fly out to Ohio’—and, of course, that’s like hell for Jeffrey, going to Ohio–‘would you fly to Ohio for several months going over all my books with a fine tooth comb and find out what’s going on?'”

On the plane to Paris, Epstein prepped Julie for the meeting. It was just going to be the three of them—Epstein, Wexner, and Julie. (Julie wasn’t attending in any official capacity. She was meeting some friends in Paris, and Epstein invited her to catch a ride with him on Wexner’s plane.) She recalled a nervous and excited Epstein telling her to be on her best behavior, worried that she might say something that would make him look bad, and emphasizing how important this meeting was.

“Wexner was this super-successful guy who didn’t really have any life, and Jeff described him to me as completely socially inept,” Julie said. ”Jeffrey was like, ‘Look at me now, wow, look at where I am,’ and it was exciting for him.”

The meeting, at least to Julie, was nothing momentous. “I remember meeting Leslie at the cafe, and all he did was eat peanuts out of the little peanut tray. And I remember, just to try and make him feel comfortable, I ate the peanuts with him….It was so incredibly awkward,” said Julie. Leslie was shy, quiet, and the meeting was short and uncomfortable—few words shared, no food served, the trio sustaining themselves on peanuts alone. In all, it was an uneventful evening, but looking back now, one can see why Epstein had been so excited about cozying up to Wexner. “Jeffrey told me, ‘This guy [Wexner] has everything in the world, but he doesn’t have anyone to share it with,’ and Jeffrey knew all the girls in the world.” That was Epstein’s MO, Julie said. “He’d take some rich guy and introduce him to a girl.” I spoke with one woman who said she met Epstein at an art fair in Palm Beach. He was direct with her. “He came up to me and said, ‘Would you like a date with Prince Andrew?’” she recalled.

In the years following, Epstein began to play a central role in Wexner’s life. “Jeffrey wasn’t just a money manager. He was a personal assistant….If Leslie had a problem with his yacht, he was there,” Julie told me. The billionaire handed over huge swaths of his finances to Epstein’s control, sold a plane and a mansion to trusts that Epstein controlled, and to the surprise of his friends and colleagues, went so far as to hand Epstein his power of attorney in 1991. “People have said it’s like we have one brain between two of us: each has a side,” Epstein told Vanity Fair in 2003. Colleagues and friends of Wexner’s were shocked at Epstein’s hold over Wexner. Julie, however, wasn’t that surprised. She recalled Epstein saying to her, “This guy has no life, and I’m going to give him a life.” It was that simple.

Epstein’s relationship with Wexner was transformative, if for no other reason than that he became incredibly rich because of it. Julie says a “huge, huge” change occurred in Epstein’s personality after his relationship with Wexner began to solidify, and particularly after he had started amassing his mysterious fortune. In fact, in her mind, three people were responsible for the changes she saw in her friend. There was Wexner. Less directly, there was Bill Clinton, who reportedly connected with Epstein through the Clinton Foundation. (“Seeing a powerful guy like Clinton get away with what he got away with,” said Julie, who never met Clinton, “I think it just emboldened him to think he could do whatever he wanted.”) And above all, there was Ghislaine Maxwell.

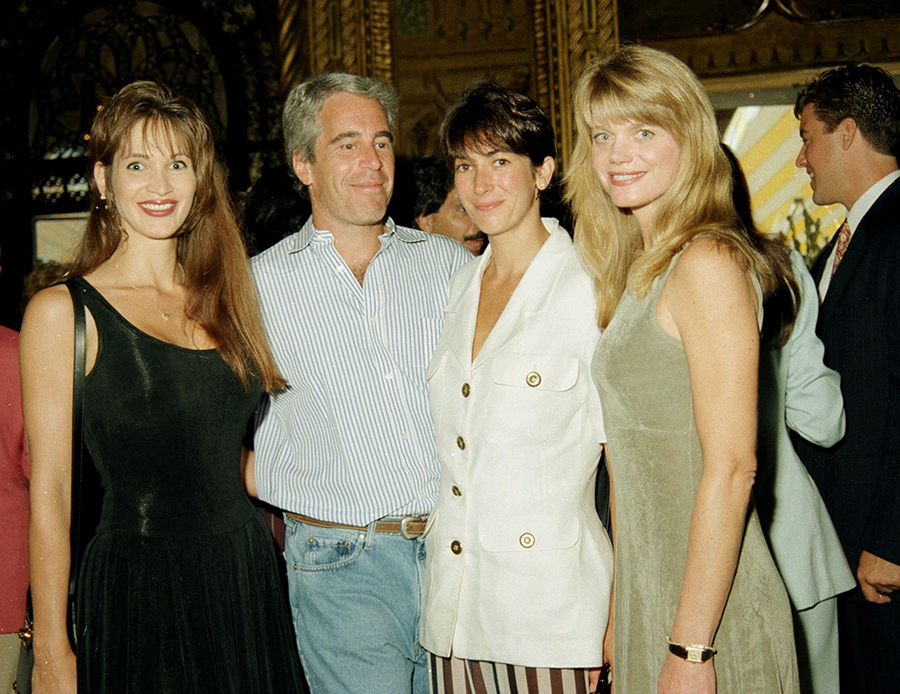

Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell in 2005.

Joe Schildhorn/Patrick McMullan/Getty

“When he was younger and living in New York there weren’t a lot of young girls. I could see it progressing as he got older, more powerful, more money,” Julie told me. “And the Ghislaine thing I think is key.”

Maxwell, the daughter of billionaire publishing magnate Robert Maxwell, is often called Epstein’s “right-hand woman.” Epstein’s relationship with her was by all accounts tumultuous, toxic, and life-altering for the both of them.

Julie related the dynamics of their relationship to me in extreme middle-school terms: At first, Jeffrey had a crush on Maxwell, but she blew him off and “treated him like crap.” Shortly after they met, Maxwell’s father died after “falling off his yacht,” as Julie put it. Maxwell was an emotional wreck, and it was here that Epstein “went in for the kill,” in Julie’s words. Apparently it worked, and even though he would soon become “bored” and “done with her,” Epstein continued to take advantage of Maxwell’s emotional vulnerability and eventual attachment. According to Julie, the remainder of their relationship was built on resentment, mutual jealousy, and a toxic codependency.

“He resented her for rejecting him when she didn’t need him, and now that she did, he was going to exploit it. She used him and he used her, and that’s where this whole sexual production line came in,” Julie told me. “She needed to be essential for him. [Recruiting girls] is how she kept her place. She had value for him….She ran his house.”

Maxwell has been widely accused of helping orchestrate Epstein’s child sex ring. Dan Kaiser, attorney for one of Epstein’s victims, said that Maxwell was “integral in maintaining the sex trafficking ring….She provided important administrative services in terms of the hiring of recruiters, and management of those employees, the making of appointments and dates for interactions between Mr. Epstein and the underage girls that were providing sexual services to him. She also maintained the ring by intimidating girls, by ensuring their silence.” Maria Farmer, one of Epstein’s earliest victims, said under oath that Maxwell brought in a stream of young teenage girls to Epstein’s New York mansion, and told the Guardian that Maxwell was “key in making me feel safe….I trusted her because she is a woman. She would make us trust her, she would make us really care about her….She was so dangerous.”

“Ghislaine controlled the girls,” Sarah Ransome, another alleged victim of Epstein’s, told the BBC program Panorama. “She would be the one getting all the girls in check. She knew what Jeffrey liked….This was very much a joint effort.”

Maxwell would also allegedly participate in the abuse. Maria Farmer and Virginia Giuffre both say that Maxwell sexually abused them.

Because of these allegations and others like them, Maxwell was on the move for almost a year after Epstein’s mysterious death. She was arrested only recently in New Hampshire and charged with “enticing a minor to travel to engage in criminal sexual activity, transporting a minor with the intent to engage in criminal sexual activity, conspiracy to commit both of those offenses, and perjury in connection with a sworn deposition.”

In the course of my project I would come to realize the little black book was Maxwell’s as much as it was Epstein’s. Dozens of people I spoke to were surprised to hear they were listed in his book, sometimes alongside their parents’ or siblings’ numbers and home addresses, and just as many claimed they had never once met Epstein. But nearly all of these people did have some kind of relationship with Ghislaine Maxwell. A friend of Maxwell who had also seen the book told me, “This looks like her address book….I know several people [in here] who’ve never met him.” I would figure about a fourth of the people listed in the black book knew only Maxwell.

Her hand in the creation of this book is clear. There are several “massage” lists—lists for California, Paris, New Mexico, and Florida, containing dozens of female first names with numbers beside each. Next to some of these names are little parenthetical notes like “GM really likes.” I spoke to one woman, a bodyworker, who has a note next to her name in the book that reads, “GM hasn’t tried yet.” “Oh!” she shouted. “That’s so fucking creepy!”

“Ghislaine was a shark,” Julie told me, “Anything you read about her that’s positive isn’t true. She’s a scary woman….The picture that Virginia [Giuffre] drew of Ghislaine? I completely believe what she wrote.” Julie told me Maxwell was Epstein’s ticket into proper high society. ”Jeffrey had money, Ghislaine had status,” Julie said. It was Maxwell who introduced Epstein to Prince Andrew, eighth in line to the British throne. In an affidavit, Giuffre claimed she was forced to have sex with Prince Andrew multiple times in multiple locations. (Giuffre was attempting to join a lawsuit against Alan Dershowitz, who succeeded in keeping other plaintiffs off the case; her affidavit was struck from the record in 2015.) Included in the affidavit was a 2001 photo of Andrew with his arms around Giuffre’s waist, a smiling Maxwell in the background.

Maxwell was indispensable to the world Epstein had built for himself, but eventually, Julie says, he wanted to dispose of her anyway. “He was mean to her in the end, when he wanted her gone. He called her brain dead, and he’d be rude to her in front of people,” Julie said, “It made my skin crawl, and I didn’t even like her….Treating anybody like that’s just not right.”

THE NON-PC STAND-UP COMIC: “ALL HE TALKED TO ME ABOUT WAS COMEDY.”

“My wife’s going to be pissed I talked to you about this,” the self-styled “pitbull of comedy” told me one day, “but look, I’ve got nothing to hide.”

This was Bobby Slayton, a stand-up comic who is notorious for his racist and sexist material. “He used to call me up and be like, ‘How do you get on stage with all this #MeToo stuff?” Slayton said.

Epstein took a liking to the comedian after seeing him perform at the Palm Beach Improv in the 1990s. “The guy was a big fan of mine, and his girlfriend [Ghislaine] called me for his 50th birthday party. She said he was a big fan and wanted me to come entertain, and that there was going to be some big, high-profile people there.

“So, I asked, what does it pay? And she says, well, it doesn’t pay anything, but we’re going to fly you out and put you up, and I said, what kind of fucking gig is this?”

Slayton mentioned to Maxwell offhandedly that he might bring his wife, to which she answered “no women.” The party fell through—or at least Slayton’s invite did—but Epstein kept in contact with the comedian, catching his shows around Palm Beach, Miami, and New York. Epstein invited Slayton to his mansion in Palm Beach for coffee and to “talk about comedy,” but when Slayton arrived Epstein wouldn’t let him inside. “He showed me the pool and the garage, his cars, but didn’t let me in,” Slayton said. He was never invited to the private island, but he once brought it up in conversation with Epstein, who responded that he “didn’t invite many people out there.” When Slayton proposed he and his wife come out to the island sometime, Epstein responded, “No, no wives.”

“Jeffrey was a giant comedy fan, huge, all he talked to me about was comedy,” Slayton said. “He was like a little kid talking about it….He loved guys with an edge. He loved Lewis Black, Sam Kinison, Bill Hicks—he liked guys with an edge.”

Epstein’s fondness for edginess went well beyond comedy. Julie told me Epstein “liked anything controversial or politically incorrect. And anything to do with the brain….If it was something that no one else would say, something controversial, even about anything racial or whatever, he was happy to say it.” She described him as “edgy” and “un-PC.” She liked that about him, but there were times it became a problem in their relationship. “I grew up really sheltered,” she said, “and I was never promiscuous or anything.” Once, at a dinner with Epstein and a male friend of his, the conversation “turned” and became “incredibly crude.” The men were talking about women, and Julie was so upset that she got up from the table and walked out of the restaurant, holding back tears, and flagged a cab to leave. Epstein followed her and climbed into the cab with her. Julie was crying. “I felt like Jeffrey was amused by me being naive….It was amusing to him.”

Julie said a friend of hers dumped Epstein for “being racist,” after a racist remark by him sparked an argument between the two. When a model in their social circle began to do nonprofit work in Africa, Epstein and several of his “intellectual” friends told her—as she phrased it— that “Africa is a waste, there’s nothing that you can do that’s ever going to help—it’s a waste of money.”

In his conversations with Slayton, Epstein was cagy, stopping short of offering his own opinion on things like #MeToo. “He didn’t really get into any of his own opinions. He just asked a lot of questions. He asked the kinds of questions that a young comic would ask in comedy class.”

Was he funny?

“No.”

THE SPORTSCASTER: “HE SAID, ‘OK, YOU CAN GO NOW.’”

“He asked a lot of questions—he didn’t talk much….He was bland,” said Suzy Shuster, an Emmy-winning sportscaster currently at the NFL Network.

Shuster was fresh out of college when she ran into Epstein and Maxwell at a social event in New York. “I just thought Ghislaine was so glamorous.” Shuster was working for Andrew Neil, then one of Rupert Murdoch’s top lieutenants, at what would become Fox News, and according to Shuster there was a great deal of overlap between Epstein’s and Neil’s social circles. A few days after meeting Epstein, Ghislaine called Shuster and told her that Jeffrey would like to have lunch with her at his townhouse in New York.

“I thought to myself, like a total jackass, I am so interesting and so smart, he must want to go on a date with me,” she said. “I was 22—what did I know?” Shuster was greeted at the door by the butler while Epstein descended the large staircase by the entrance, dressed in a sweatshirt and jeans. Epstein gave Shuster a full tour of the house, including the master bedroom and massage room, the same room where dozens of alleged assaults took place, and he had his staff serve them lunch in the large parlor downstairs.

Shuster was just about to begin coverage of the ’96 election, but Epstein didn’t offer his own views about the election during the conversation, or about anything really. “He had a really disarming way of making himself appear brighter than he was,” Shuster said. “But you knew you weren’t sitting with the brightest person in the room.”

After an hour and a half, Epstein abruptly ended the conversation. “I remember clear as day,” Shuster said. “He said, ‘OK, you can go now’, and he just went down into his garage and in his car, and I just walked out.”

Epstein’s Manhattan townhouse was raided by the FBI in 2019.

Nancy Kaszerman/ZUMA

THE ART STUDENT: “I REMEMBER BEING SO SCARED THAT I WOULDN’T GET OUT.”

“He was supposed to invest in my screenplay,” said a woman we’ll call Tracey. When working my way through the book, I’d tried to steer clear of any known victims. But given the large swath of victims Epstein had accumulated, it was bound to happen that I would eventually find someone who had been assaulted by Epstein. My phone call with Tracey was by far the most difficult of the entire experience.

Tracey first met Epstein through a fellow student in an NYC art school in 2001. Tracey told me her friend had been commissioned by Epstein to paint, and that she tried to get Tracey to go on a date with Epstein. Tracey had a boyfriend at the time, and she declined. But when her friend told her that Epstein was a “philanthropist who funds artists” and would fund a screenplay she was working on, Tracey agreed to meet with him in his New York townhouse. “I was there on a business meeting. I was dressed for business. I had a boyfriend.”

The butler answered the door, and down the stairs came Epstein, wearing a white T-shirt and ripped-up jeans. Tracey was taken aback by the size of the staff at the house, “People came in with food,” she recalled. “People were asking me if I wanted massages. I told them no.”

She remembered climbing a marble staircase and walking into a “huge, grand room.” Epstein “acted like a gentleman for two hours,” Tracey said. “We talked about Dolly”—the sheep cloned in 1996, to great fanfare—“and the whole cloning thing, and he told me he had a place down in Mexico that was already working on cloning humans.

“We had an interesting talk for about two hours, and at the end of the meeting he groped me. I started crying and wanted to get out, and I remember being so scared that I wouldn’t get out, because there were so many people working there. I really thought I might not get out of there.”

Epstein tried to hand Tracey a check, ostensibly for the screenplay Tracey had gone there to discuss, but she turned and fled out the door. She called her boyfriend immediately after the incident and has never told more than a couple close friends about it since. She thought about speaking out when the first round of allegations became public, but she decided not to, out of fear for her safety. “I was always afraid, because I knew he was really powerful. And you’re going to think it’s totally crazy, but I bet you he cloned himself, and whoever killed themselves was a clone….I try not to think about it. I wouldn’t put it past that he’s out there somewhere. He said he had a lab in Mexico, because the Dolly thing got shut down.”

After the incident, Tracey was inundated by phone calls from a woman asking her to go to dinner with Epstein. Tracey confronted her friend who had recommended the meeting and learned that the paintings her friend had been commissioned for were “paintings of vaginas.”

“She didn’t warn me. She didn’t seem surprised. I was kind of mad at her,” said Tracey. “When [I told her what happened], she said, ‘He just likes to watch people shower. He won’t touch you.’ I said, ‘Are you crazy?’” Tracey told me that she reported the incident to the New York attorney general’s office after Epstein’s arrest in 2019. Still worried about her name getting out and inviting retribution, she submitted the tip through the office’s website.

THE YOGI: “I SAW THE WHOLE THING START TO FORM.”

Calling people up and asking them about Jeffrey Epstein resulted in a lot of panicked hangups, which was expected. One day I called up the number listed in the book for a financier named David Mitchell, who identified himself on the phone to me as David Mitchell after I asked for David Mitchell, but when I mentioned Epstein suddenly he insisted I had the wrong number. The next day I read that Epstein’s bond was “co-secured by his brother, Mark Epstein, and a friend identified as David Mitchell.” Joe Pagano told me “I never met him” and “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” despite profiles identifying him as a close friend of Epstein.

Others seemed willing to talk, if haltingly, only to turn on their heels later on. One particularly ominous interaction was with Epstein’s personal yoga instructor, who met him in 1992 and traveled with him and Ghislaine as a personal yoga teacher. For the 15-minute phone call he somberly beat around the bush, speaking in long, thoughtful pauses and letting his sentences trail off. “I met him on his 39th birthday. The last time I saw him it was shortly after Clinton left the White House—it was 2001, maybe 2002. I was with him in Palm Beach; Columbus, Ohio; and New York, Santa Fe….I did a lot of—it’s a long story, it’s a complicated story,” he told me. “It’s a long story.”

“I spent a lot of time with Ghislaine, she gave me a lot of insights. My last contact with her was—she used to come out here with Prince Andrew.”

What was Ghislaine like? “Oh, god, that’s a whole other story.”

I said he could tell me the full story sometime, and that if he wanted I would keep his identity under wraps. He said no: “A lot of people would figure out in a nanosecond who it was. It was a small little group. I don’t imagine many of them are going to talk….Look, I’ve worked with Rupert Murdoch on the far right and Zack de la Rocha on the far left. I try to keep my mouth shut….My contacts were very broad.”

He went on, slowly, in a kind of far-away melancholy: “I saw sides of both of them [Epstein and Maxwell] that most people didn’t see….I saw the whole thing start to form.” By the time I called him a few days later, he’d had a change of heart. He began shouting at me over the phone about how he planned on suing me, that I was to not print anything we spoke about.

Julie repeatedly told me she never witnessed any kind of “darkness,” but that, looking back, she regrets not picking up on what she now sees as red flags. “I wish when he told me he was doing ‘naughty things’ in Florida I took it seriously,” Julie said.

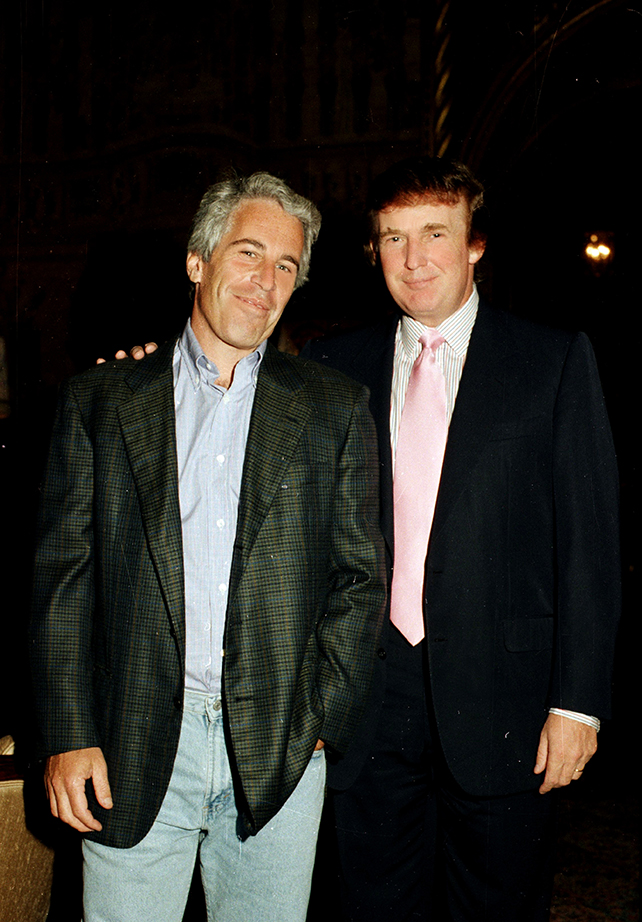

Epstein’s affection for young women was no secret. As Donald Trump put it in New York Magazine in 2002, “It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side.” Epstein was very aware of his reputation and reveled in the attention it got him.

Epstein and Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago in 1997.

Davidoff Studios/Getty

“I remember he was dating Shelley Lewis, she looked like a little, completely undeveloped girl,” Julie said. “She was definitely legal age, but she looked really prepubescent, physically….He was walking around [a popular mall] with her and finding it funny that people thought he was her father.” If Epstein was at all embarrassed about the nickname given to his Boeing 727, “The Lolita Express,” he didn’t show it. “He had the book [Lolita] around, you know, he had multiple homes, and there’d be a Lolita on the table somewhere….He had more than one copy,” Julie said. “He always thought it was funny.”

What seem now like obvious signs of trouble had tidy, unquestioned explanations at the time. The young masseuses at Epstein’s side, for instance: “I knew that Jeffrey needed a lot of massages, so it didn’t seem odd,” Julie said. I asked why Epstein “needed” a lot of massages, expecting some answer about a physical ailment. But instead Julie told me that Epstein had said that his “ADD tendencies” necessitated frequent massage for him to “clear his head.”

Much of Epstein’s personality that was chalked up to eccentricity by Julie at the time now seems incredibly fucked up in retrospect. “I used to call him on his birthday,” Julie said, “and he was always really short on the phone, but sometimes he would sort of snicker and laugh and say, ‘Oh, I’ve been so bad.’….I didn’t know what it meant at the time, and he used to be full of crap sometimes and say things to try and make himself look interesting, but now I do.”

Epstein called Julie after his sentencing in 2007. “He said, ‘I’m going to jail,’ and didn’t explain why. And afterwards I started to pay attention to the case…and when he got out, I just thought, this guy hasn’t learned anything.” She cut ties with him after his sentencing.

Julie recalled that Epstein had a habit of telling inappropriate stories about the daughter of one of his girlfriends, a woman Julie knew as well. “Some of them would be like—you know, sometimes little kids say sexual stuff, and it’s just innocent, but he’d repeat those stories because he thought they were really funny, and I thought he was a little too interested in that. I remember thinking they weren’t that funny….Why would an adult tell this story?” said Julie. “I just remember being slightly uncomfortable, not like I thought he was going to be a predator, but just that it was a little inappropriate.”

She shared with me an idea of hers that she seemed uncomfortable even to speak out loud: that Epstein’s “sickness” had its roots in his relationship with this particular girlfriend. “He loved [her], but she was never going to marry him, and it wasn’t going to work,” Julie said. “He loved her more than anyone. She was like family. And then she has this beautiful daughter.” The girl, in Julie’s estimation, was like a miniature version of her mother. “I think that might’ve been what got his interest” in young girls.

Julie was only speculating. What she didn’t know is that, in the back of my copy of the black book, there are a couple pages handwritten ostensibly by Rodriguez, the butler. Reading it, I get the sense that Rodriguez was compiling an addendum to the book in order to aid law enforcement. On one page, titled “important email / address,” Rodriguez lists the personal emails for Epstein and Maxwell, as well several listings with tags next to them like “witness – interacted and chat daily with underage girls,” “important witness,” and “scout for young Pamelas,” whatever that means. Another name and number is tagged as “In House Citrix Systems Programmer,” right next to another listing for Ehud Barack’s secret service personnel. Months after Julie told me about the girlfriend and her daughter, I reread the handwritten page attached to the book and saw the girlfriend’s name and phone number near the bottom, with a tag next to her entry reading “former model & mother of naked pic.”

On one of our last phone calls, Julie broke down. It was late at night, and Julie, who tried to steer away from news about the Epstein case, had just watched the Netflix documentary Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich. The documentary features several in-depth interviews with some of Epstein’s victims, and they each walk through the details of their assault at his hands. The atrocities that Epstein committed and the scope of suffering he exacted on his victims had become real and undeniable. She wept as she recalled diary entries she’d read earlier in the day. “He was a monster—what he did was so sick, you know, and then I read my diary, and saw how nice he was when I was going through [a major family crisis] or a breakup or something, and it hurts to still miss that part of him,” Julie said. “He was my friend.”

Deborah Blohm, Epstein, Maxwell, and Gwendolyn Beck at a 1995 party at Mar-a-Lago.

Davidoff Studios/Getty

THE ASSISTANT’S OLD HIPPIE MOTHER: “HE THOUGHT SHE WAS A REALLY INTELLIGENT BLONDE.”

Transcript of a phone call with a self-described “old hippie,” whose teenage daughter began working for Epstein in his Palm Beach mansion around 2002, just a few years before Epstein’s first arrest.

Me: How much time did she spend with Epstein at his place?

Old hippie: Quite a bit.

Me: So this all must have been difficult for her then?

Old hippie: No, it’s not difficult at all. Why would it be difficult? Tell me why you think it would be difficult.

Me: Well, just the proximity alone to something that happened that was so horrific.

Old hippie: Well, you know what? I think [laughing], if people take payment, and he paid people well, then, later they shouldn’t complain. I mean, that’s, you know, one thing [my daughter] said one time, too.

Me: OK. And did [your daughter] get paid well, too?

Old hippie: Yeah, sure.

Me: OK. How did she end up getting that job?

Old hippie: Well, she’s a gorgeous blonde [laughing].

Me: [Nervous, uncomfortable laughter.] Yeah, well, a couple of Epstein’s friends told me that if he ever needed someone for a task or whatever they would find him a beautiful young blonde to do it.

Old hippie: Well, she’s beautiful. She’s 6 feet tall. She’s gorgeous….My daughter is a very strong person.

Me: You said she got calls from some reporters and got sick of it?

Old hippie: No, she only got a few calls, and she had nothing to say. There’s nothing negative to say.

Me: Do you think she’d be interested in talking to me?

Old hippie: I don’t think so. I probably already told you more than she would.

[Here I let her know I’d be interested in hearing her daughter’s story.]

Old hippie: Well, I remember one other thing. When he was going to, um, Africa, with Bill Clinton? You remember that?

Me: Yeah.

Old hippie: Well, Jeffrey wanted her to go.

Me: Oh, really.

Old hippie: She said no.

Me: What’d she say no for?

Old hippie: She didn’t want to get any shots.

Me: Oh, wow. Really dodged a bullet there.

Old hippie: It wasn’t important to her. But he really wanted her to go because he thought she was a really intelligent blonde….Let me ask you something, do you think he killed himself?

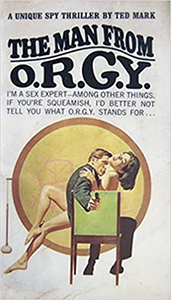

THE MAN FROM O.R.G.Y.

Months after Epstein’s death, I dialed up the last remaining listing in my book–a random number in the UK. It was disconnected. The media had mostly moved on from the case, and I was left to sift through the hours of interviews I’d done over the course of some 2,000 phone calls. One thing was abundantly clear: Epstein’s black book does not offer a portrait of a guy with many friends.

The book is the product of a systematized effort to collect human beings. A huge number of the relatively normal, professional-class people I spoke to were shocked their number was in the book at all. Either they said they had never met him or that they had had a single, superficial interaction with him. It’s as if Epstein had tried to reverse the usual dynamics of fame and power: He seemed to know more people than knew him. If Epstein had a talent, it was for knowing how much of his interest he needed to parcel out in order for people—scientists, stand-up comics, aspiring models—to feel flattered by the attention.

There were plenty of clues that Epstein was a poseur. Ask around the finance world and you’ll be hard pressed to find anybody who actually traded with the supposed billionaire investment broker. Ask the scientists in his orbit and they’ll tell you, as Stuart Pivar told me, that he “didn’t know shit from Shinola about science.” (Steven Pinker, trying to distance himself from Epstein, told New York magazine, “Despite what various friends and colleagues all said about what a genius he was, I found him tedious and distasteful…a kibitzer more than a serious intellectual.”) Ask the art people in his life and they’ll tell you about the fakes and forgeries. “He was amused to put one over on the world by having fake art,” Pivar told me. “He thought that he was seeing through the fallacy.”

And yet Epstein’s reputation for genius persists. Most of what I heard Epstein’s peers adduce to his brilliance amounted to no more than half-baked contrarianism (“He wasn’t afraid to stir things up”) or boilerplate TED-talk drivel (“Jeffrey was a big fan of transhumanism”). When I pressed people to tell me about the guy, about what he thought about the world, they rarely had an answer. I was repeatedly told that he never really got into what he thought about whatever particular subject was being discussed, and that he had a knack for making himself seem smarter and more interesting than he really was. Every time I did manage to drill down into something concrete, some actual idea or thought of his, it was a mixture of psychotic Silicon Valley drivel and freshman-year bongwater philosophy, delivered to me with total reverence. “You have to write this in your story, this is something I learned from Jeffrey, this was his line,” Julie told me. “‘People make mistakes because they don’t think about what they can lose, only what they can gain.’ This is what I took from him.”

After Epstein’s arrest in 2019, a media narrative coalesced around the question of his strange place in the global elite: Epstein the master salesman, a man who had skillfully conned his way into the world’s most powerful circles, fooling everyone in the process. But after my travels through the book, after hearing more of the petty gossip and childish drama of the people who rule our world, I realized this was obviously incorrect. Built into the premise of Epstein the mastermind scammer is the notion that some kind of legitimate path to a legitimate global aristocracy exists. To call Epstein a grifter is to assume he circumvented some genuine meritocratic world order, where the “real” virtuosos dutifully climb the “real” ranks into the oligarchy, powered by nothing but their native talents.

The truth is that the elite world that Epstein ascended into, the one I tapped into by way of the black book, is populated with hordes of loathsome, boring, untalented people living their bumbling, idiotic lives while just so happening to wield some share of the preposterous global bounty that he and the rest were after. For all the mystery surrounding Epstein’s fortune, its existence is hardly more inscrutable than the wealth of any of his other billionaire peers. He earned it the same way they all did, which is to say precisely not at all.

This wasn’t some masterful hack into the global aristocracy. It’s what everyone does. It’s what the whole thing is. There is no scam here. It’s grifters grifting grifters all the way down.

Maxwell, Epstein, and musician Michael Bolton at Mar-a-Lago in 2000.

Davidoff Studios/Getty

In a way it’s easy to understand the impulse of Epstein’s network to make him into something more than he was. The self-flattering idea that there was some ineffable substance to him, some bright light within, that explains the ease with which he accrued social and temporal power has a match in much of the conspiracizing about the scandal and his death. The difference is, the conspiracy theories actually seem plausible.

But maybe this is simply a product of my own Epstein-addled brain—it’s impossible to tell. I’ve now spent more than a year falling down a series of rabbit holes, thus far withstanding permanent psychic damage. I can report that the current grand unified theory of Jeffrey Epstein goes like this: He was indeed operating a child sex ring; he was videotaping members of the global elite engaged in sex acts with underage girls on his private island; and he was using this footage to blackmail them, either for his own personal enrichment or on behalf of any number of intelligence agencies. The Epstein-as-intelligence angle posits either that he was conducting the sex trafficking at the governments’ request or that he was already doing the trafficking when governments took notice and started using him as an asset. The theory neatly justifies both his untraceable wealth and outlandish special treatment in the criminal justice system, and there is some compelling evidence to go along with it: When prosecutors raided his home in 2019, a safe was found containing multiple CDs with the label “Young [Name] + [Name].” Also found was a fake Austrian passport containing his photograph and a spoofed name that listed his residence as Saudi Arabia (this safe also contained 48 loose diamonds and $70,000 in cash). In August 2019, citing a friend of Ghislaine Maxwell, Vanity Fair reported that Epstein and Maxwell had the island home “completely wired for video,” and that they were videotaping their guests as a form of blackmail. Both Virginia Giuffre and another Epstein accuser, Chauntae Davies, make similar allegations. When I mentioned the video surveillance to Julie, she said: “Oh, yeah, there’s a security room with a bunch of TVs. Jeffrey introduced me to the guy who watched them.”

But the most damning evidence of an Epstein conspiracy is the absurd plea deal offered by US Attorney Alexander Acosta in 2007 after investigators had identified dozens of underage girls who’d been sexually abused by Epstein. Acosta granted federal immunity to “any potential co-conspirators” of Epstein’s, an absolutely unheard-of provision, particularly in the case of an alleged serial child molester. Also within the plea deal was another unheard-of provision stating “this agreement will not be made part of any public record,” a coverup that was found to be illegal—until an appeals court reversed it on a technicality. Calling this a sweetheart deal doesn’t even come close to capturing it—the feds never introduced a 53-page indictment they had prepared, and even though nearly 30 victims were interviewed, Epstein ended up being charged only with the procurement of an underage girl for prostitution. The feds dropped their case, and Epstein ended up serving 13 months in a private wing of a Palm Beach County jail, where he was chauffeured to and from a luxury office space for 12 hours a day and allowed to receive female visitors.

The worst part is that this coverup essentially worked for over a decade. Alfredo Rodriguez, the butler who attempted to sell the black book, served more jail time than Epstein ever did for serially molesting underage girls. New York brought new charges against Epstein, arresting him in an airport in July 2019. In an effort to find out more about the infamous plea deal, I spoke to several members of Epstein’s 2007 defense team, including Alan Dershowitz, who told me the plea was put in place to “protect the women,” which is very clearly horrendous bullshit that makes no sense whatsoever. Spencer Kuvin, who represented some of Epstein’s victims, flat out accused the DOJ of attempting to protect people like Ghislaine Maxwell with the co-conspirator provision. My efforts (and those of many other reporters) have to this day failed to uncover a single shred of an even passable answer as to why Epstein was offered a plea deal that was so good it was illegal.

In 2019, journalist Vicky Ward reported that Acosta, then in charge of Trump’s Labor Department, had told the president’s transition team that he cut the deal with Epstein’s lawyers after he had been told to “back off.” According to Ward, he had explained himself to Trump’s team by saying, “I was told Epstein belonged to intelligence and to leave it alone.” The rumors of Epstein the spook are not new. In 1992, in the first-ever public profile of Epstein, Mail on Sunday reported that “little is known of Mr. Epstein. One outrageous story links him to the CIA and Mossad….[T]he most intriguing rumour is that he was a corporate spy hired by big businesses to uncover money that had been embezzled.” When I asked Gloria Allred, who is now representing several of Epstein’s victims, about the inscrutable plea deal, she told me: “There is no good answer—it doesn’t exist, and that’s why you can’t find it. Sometimes not finding the answer is the answer.”

The dark carnival that is the Epstein case ended with his mysterious death while awaiting trial in the Metropolitan Correctional Facility in August of last year. According to the New York City medical examiner, Epstein hanged himself with his bedsheet either on the night of August 9 or early in the morning of August 10, which if true, would make his death the first acknowledged suicide in 14 years at the institution. The cause of his death and the circumstances around it are widely contested–around half of Americans believe he was murdered. A medical examiner hired by Epstein’s brother ruled the death a homicide by strangulation, citing Epstein’s broken hyoid bone, a small u-shaped bone just above the Adam’s apple that rarely fractures in instances other than strangulation. The wounds on Epstein’s neck, which drew blood, were not under the mandibles, as is usual with hanging victims, but instead around the middle of the neck, which is consistent with strangulation. The wound was also thin and wirelike, much thinner than a bedsheet, and photos of Epstein’s cell show the bedsheet itself was not bloody. While this is certainly a curious set of circumstances, none is a smoking gun in and of itself. But there are more, even stranger details around what Attorney General William Barr has described as “a perfect storm of screwups.” Epstein had been placed into a Special Housing Unit after an earlier suicide attempt and was to have a cellmate and wellness check every 30 minutes, two protocols that were not followed on the night of his death. The two guards were charged with falling asleep at the desk and later falsifying the necessary records. The three cameras with views of his cell simultaneously malfunctioned—two had died, and one had produced footage that was deemed “unusable”.

Almost everyone I spoke to expressed either doubt or total disbelief that his death was a suicide. Only one person—Alan Dershowitz—believed outright that he had killed himself. A woman who didn’t know Epstein well but was close to members of his inner social circle told me: “It smells to me….I’m not going to give you any names, but there’s definitely people closer to this story that don’t think he killed himself.”

It was Epstein’s inexplicable death that ushered in a frenzy of conspiracy theories. Everywhere you looked in Epstein’s life were nauseating sets of compounding coincidences, and it seemed that every bizarre detail unearthed led to 10 or 20 more. Building off Epstein’s enigmatic reputation and the reports then coming out about his freakish scientific pursuits, some of the conspiracizing became fevered, grandiose, even occultish, with Epstein depicted as a high-ranking official of some secret world order.

This urge to make Epstein’s power sophisticated and complex serves a similar purpose as the elites’ insistence on Epstein’s extraordinary genius–both are ways of squaring the evident smallness of the man himself with the vastness of the world he built and the seemingly outsized influence he possessed. Both of them betray a collective lack of imagination when it comes to just how ludicrously rewarded dumbasses can be in this country. Epstein didn’t have to be anything special to become a key player in an evil conspiracy. He had to be rich, and he had to be useful to people richer and more powerful than he was. The very real possibility is that Epstein was both a rich dumbass and a key player in an evil conspiracy, because evil conspiracies require nothing more.

During one of our last conversations, Julie mentioned, in throwaway fashion, a diary entry she had stumbled upon about a book recommendation from Epstein. Summarizing for me, she explained that she’d asked Epstein why he had so many girls around. “I asked him why he was like this,” she recalled, “and he said to me to read some book….He told me it influenced him to become wealthy.”

The book was The Man From O.R.G.Y., an obscure 1965 James Bond ripoff written by Theodore Mark Gottfried under the pen name of Ted Mark. It’s about a con man who travels the world under the guise of being a “sex researcher” in order to spy for the US government. The novel begins with protagonist Steve Victor in Damascus for the kickoff of an “extensive survey of Arab and Oriental sex practices.” There he is approached by a US diplomat and invited to the embassy. In short order, Victor is recruited to spy for the US government.

This research program you’re engaged on, Mr. Victor, gives you entry to places the United States government could never officially investigate. The key to a factor which might prove quite vital in our handling of international power politics lies in one of these places.

The novel is an unbearable horror show. It’s violent and grotesquely pornographic, containing toddler brothels and graphic details of children and infants being ceremonially raped and trained into sex slavery. The protagonist gets custody of such a slave from the US embassy–his fake research organization, O.R.G.Y, stands for Organization for the Rational Guidance of Youth. The girl tells him about being penetrated multiple times a day since age 3 as training for a life of sex slavery, as well as the brutal beatings that were part of her training. She tells him that girls enjoy being raped. Victor gawks at and participates in this sexual mayhem, all the while using his cover as a “sex researcher” to spy on Syrian sheikhs, steal Soviet launch codes, and eventually bring on the downfall of Nikita Khrushchev.

Julie didn’t know what the book was about, but she remembered the conversation well. “It was one of the last things we talked about….He said to me, ‘Read this book, and that will help you understand,’” Julie told me. “I never read it and don’t think I ever will.”