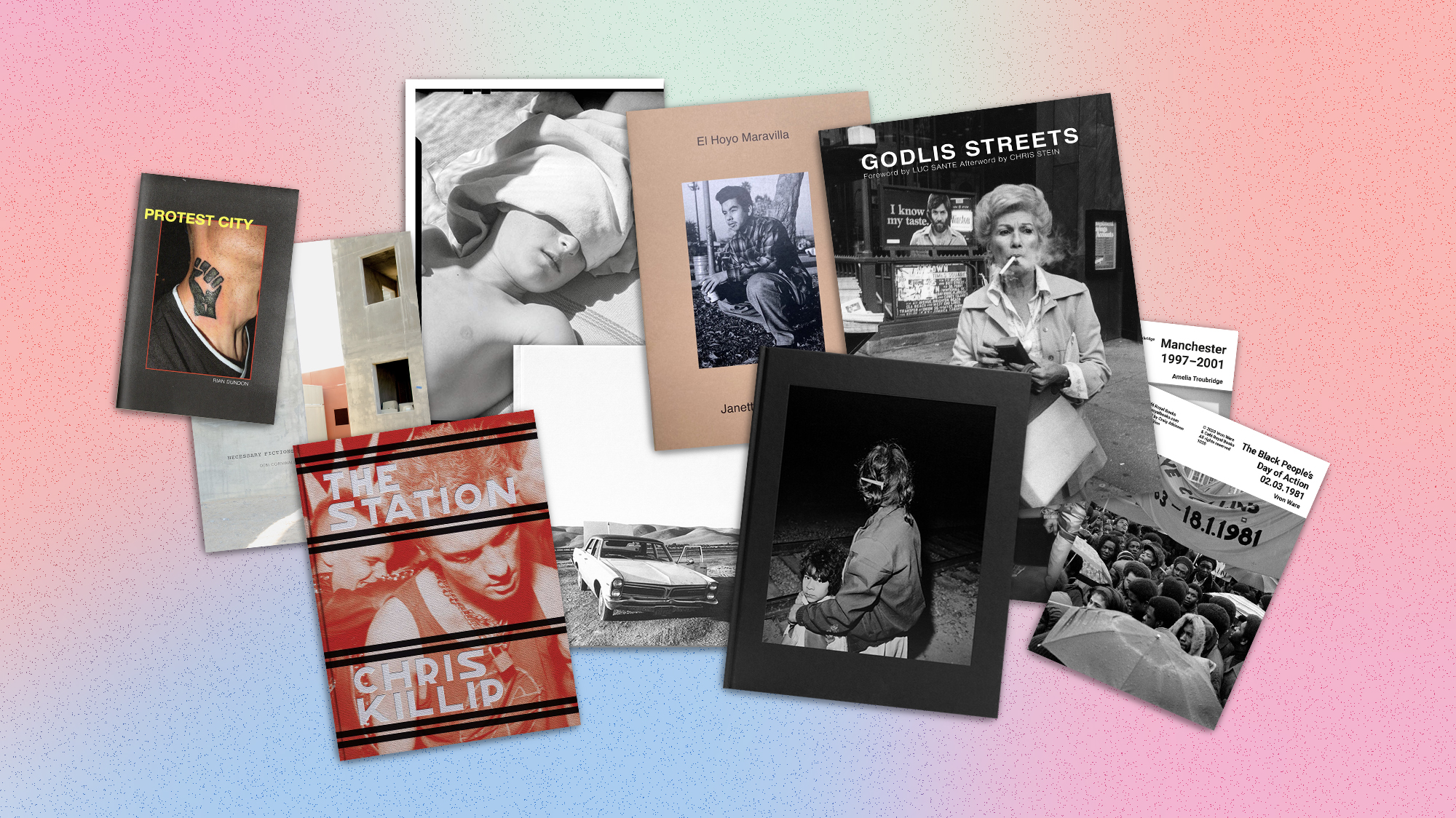

When I sat down to write up my favorite books of the year, I realized, unexpectedly, a number of them are of work made in the past. Not re-published books, but work coming out now for the first time, photographed in the ’70s and ’80s. A sign of the times, or of my own preference in photobooks these days? The pandemic may have played a small role, scuttling plans to work on and finish books. Whatever the reason, it’s been great to see excellent work saved from obscurity, published or re-imaged, as is the case with Sam Contis’ book Day Sleeper, in which she revisits photos made by Dorothea Lange.

A couple notable exceptions to the throwbacks are works by Rian Dundon and Lam Yik Fei. Dundon has been out on the street of Portland nearly every day since May 29, documenting the protests, and his work is collected in two excellent zines, Protest City and Protest City 2. Likewise, Lam brought New York Times readers stunning work from the frontlines of the Hong Kong protests, collected in a Kickstarter-funded photobook, Won Yuhng.

This selection isn’t meant as a buying guide so much as highlighting photobooks and zines that resonated over the year. As such, some are already out of print, but still worth tracking down.

Debi Cornwall — Necessary Fictions (Radius)

Though the term “necessary fictions” might sound like a glib remark from Kellyanne Conway, from the perspective of Debi Cornwall’s new photo book, it is much more a Rumsfeldian turn of phrase.

This book is a follow-up of sorts to Cornwall’s exceptional examination of the prison at Guatanamo Bay—exploring the prison itself, prisoners who have been released, and the incongruity of it all. In her newest work, Cornwall turns her eye to the mock villages and cities built on military bases around the United States with the idea of giving soldiers realistic training before landing in Iraq or Afghanistan. It’s a theater of the absurd, or a “necessary fiction.” Iraqi refugees are paid to act as locals living in these villages, to foment faux trouble for the trainees. Soldiers involved in the training protocol move through these areas with B-movie-like FX prosthetic war wounds. Everyone wears laser-tag-like gear. It all makes sense when looked at through the lens of war. Though if you step back just a bit with a critical eye, the farce of it goes beyond the feeling of being on an old movie set taken over by 256th Infantry Brigade of the Louisiana National Guard. And this is where Cornwall’s work really shines: She intersperses the detail shots of mock villages, portraits of the role players, and a portfolio of fake wounds with pages of text. Cornwall quotes from training manuals, politicians’ statements on war, and interviews she’s conducted with both civilian and enlisted role players. It’s these carefully selected words that brings the project into relief, taking it beyond being a curiosity.

It’s a smart book. The photos are great, but all in all, as a book, it’s exceptional.

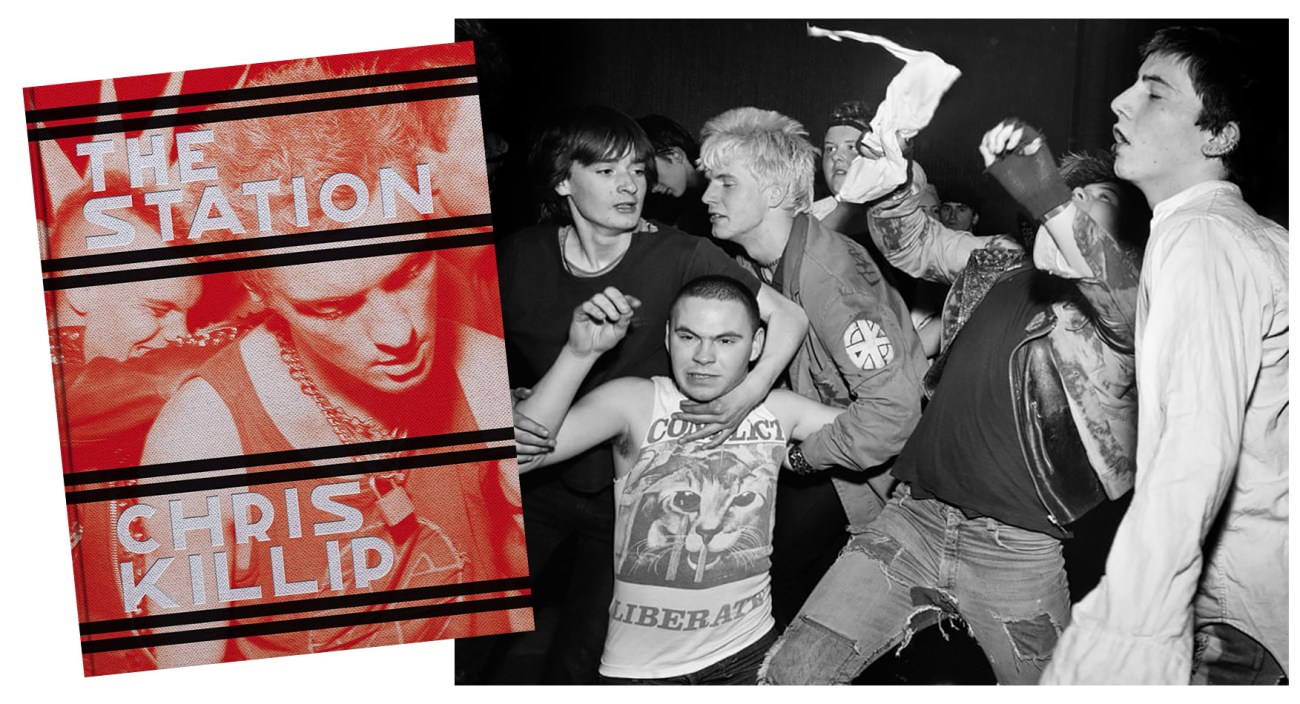

Chris Killip — The Station (Steidl)

The Station is notable for being the final book Chris Killip published before his death this year. It’s also notable for being thoroughly awesome—an in-the-pit look at small-town UK punk circa 1985.

Killip wasn’t a punk, but as an avid chronicler of British life, he made his way to The Station, a punk club in Gateshead, a large town in Northeast England, across the Tyne River from Newcastle. More than focusing on bands, Killip turned his 4 x 5 camera on the punks in the crowd. The large format of the book—tall, not thick; this isn’t a heavy tome—and gorgeous printing fits the subject, as counter-intuitive as that may seem. It puts you right there. You can almost feel (and smell) the flesh and sweat and spikes and leather of the punks dancing to songs railing against Thatcher and Reagan. This work sat largely untouched for decades. Killip’s son found the contact sheets in 2016 and prodded his father to publish it.

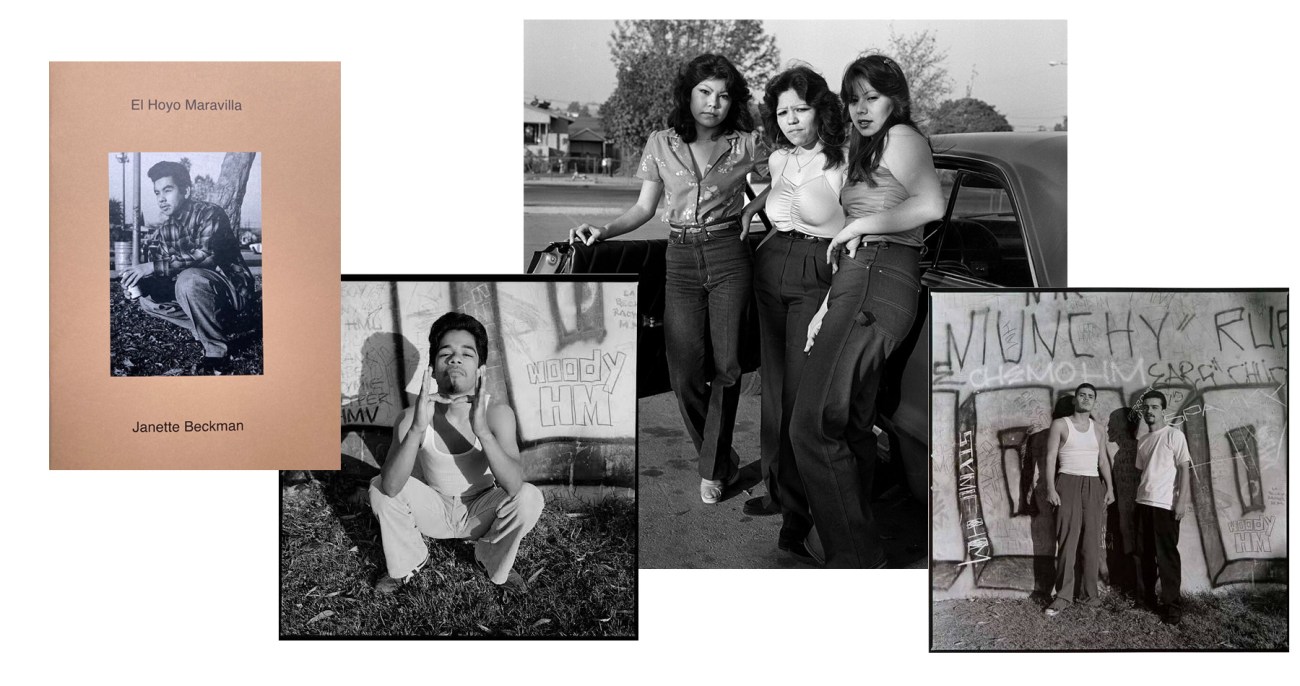

Janette Beckman — El Hoyo Maravilla (Dashwood)

The story goes something like this: British music photographer Janette Beckman was in Los Angeles in the early ’80s to check out the punk scene. She ran across an article about an East LA gang known as El Hoyo Maravilla. The reporter took Beckman out to Maravilla Park and introduced her. Beckman set out, making incredible portraits of these kids. Beckman says everyone had their poses down. And though there’s plenty of standing tough against heavily graffiti’d walls, this small book (a zine, really) captures these East LA kids with the same intensity Beckman photographed first-wave UK punks and New York City B Boys of the ’80s.

Mimi Plumb — The White Sky (Stanley/Barker)

Though Bill Owens’ classic photobook Suburbia covered some of the same ground, Mimi Plumb’s look at the still-young East Bay suburbs of the mid-1970s has something more of an eye-level view. Less voyeuristic. In her early 20s, just at the start of her career, Plumb returned to her hometown of Walnut Creek, photographing what had been her youthful stomping grounds. With a focus on children running amok through the hills and neighborhoods, Plumb’s knowledge of this land, her inspired eye and beautiful, raw talent, lets this life shine.

A lot of the photos are quiet, yet tight with tension of looming development, looming adolescence, looming trouble. There’s an innocence here—or more, the feeling of being on the edge of a loss of innocence. The book carries a stillness of a pond with a rock about to be thrown into it. It’s likely this undercurrent comes partially from the work being released almost 40 years after it was made. We know where the story goes. It’s taut with a restlessness vibrating through Plumb and into the photos. And that’s to say, The White Sky delivers more than a hit of nostalgia. Yes, it captures a time and place gone forever, but the simple beauty found in a very mundane place makes these photos, this book, special.

Café Royal Books

Since 2005, Craig Atkinson from Café Royal Books, a prolific zine publisher, has produced what has got to be one of the most thorough visual documentations of a time and place. Focusing exclusively on the British Isles (and British photographers making work elsewhere), Café Royal produces simple photo zines—and a lot of them, roughly 70 titles a year. Atkinson has a deep vein of work to mine, covering the deepest crevices of British life, high points and low. Most of the zines tend to focus on work made in the ’60s through the ’90s: Protests and riots, seaside vacations, workers on the job. Playing and fighting. It feels as if Atkinson is reviving, if not saving work that would otherwise be forgotten as neglected negatives on sagging shelves. From heavyweights like Martin Parr and Chris Killip to many, many more lesser known photographers, Café Royal’s offerings are always a treat. Very simple layouts, focusing on the work. This year’s standouts include…well, honestly, there are too many to list. It’s not cheap, but the best bang for your buck is the annual subscription.

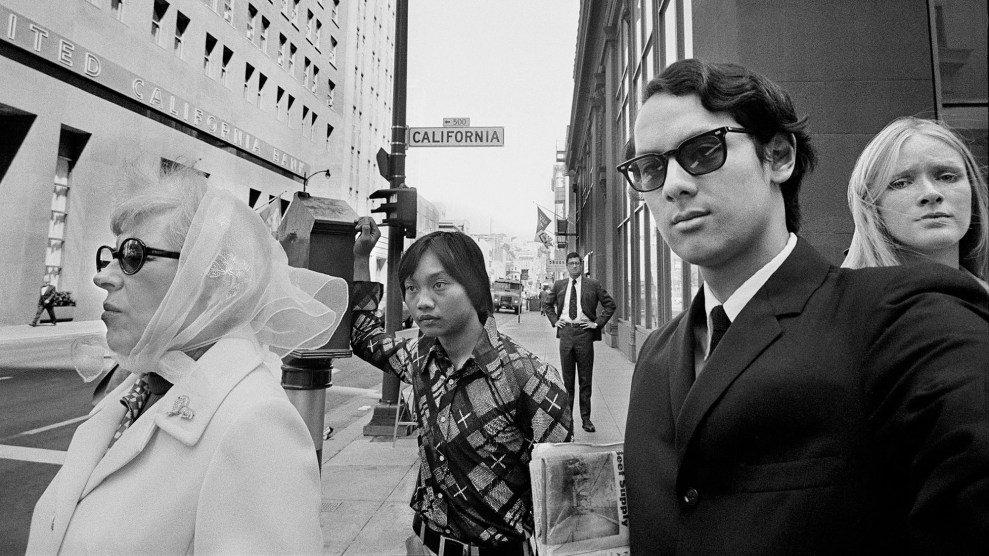

Godlis — Godlis Streets (Reel Art Press)

You likely know a David Godlis photo, whether you realize it or not. This is especially true if you like rock and roll, particularly if you like New York 1970s rock and roll. Or, even if you don’t, you probably still know a Godlis photo. Patti Smith gently touching her face at night under a Bleeker Street sign. The Ramones belting one out at CBGB’s. Debbie Harry on the prowl.

This book is not a book of the Godlis photos you know, but it’s of the same time, of the same style. Like a lot of photographers, he regularly carried a camera, taking photos of what’s around him. Godlis captured that era of New York. All the grit and grime and everything people hated at the time but romanticize now, whether they were there or not: businessmen walking under XXX movie theater signs in Times Square, women with amazing wigs smoking incredible cigarettes on the sidewalk.

Boiled down, Godlis Street is more than a dizzy romp through a fantasized, fetishized New York. This is raw, exceptional street photography. It’s loose, but not overly so. It’s black and white and grainy, but not for effect. Godlis was a young man with a camera and wide open eyes taking in what he saw. F/16 vision. Taking it all in. It’s great to see Godlis get his due in this regard. If you happen to follow him on Instagram (you should), you’ve seen these photos and hoped for a book. Dreams do come true.

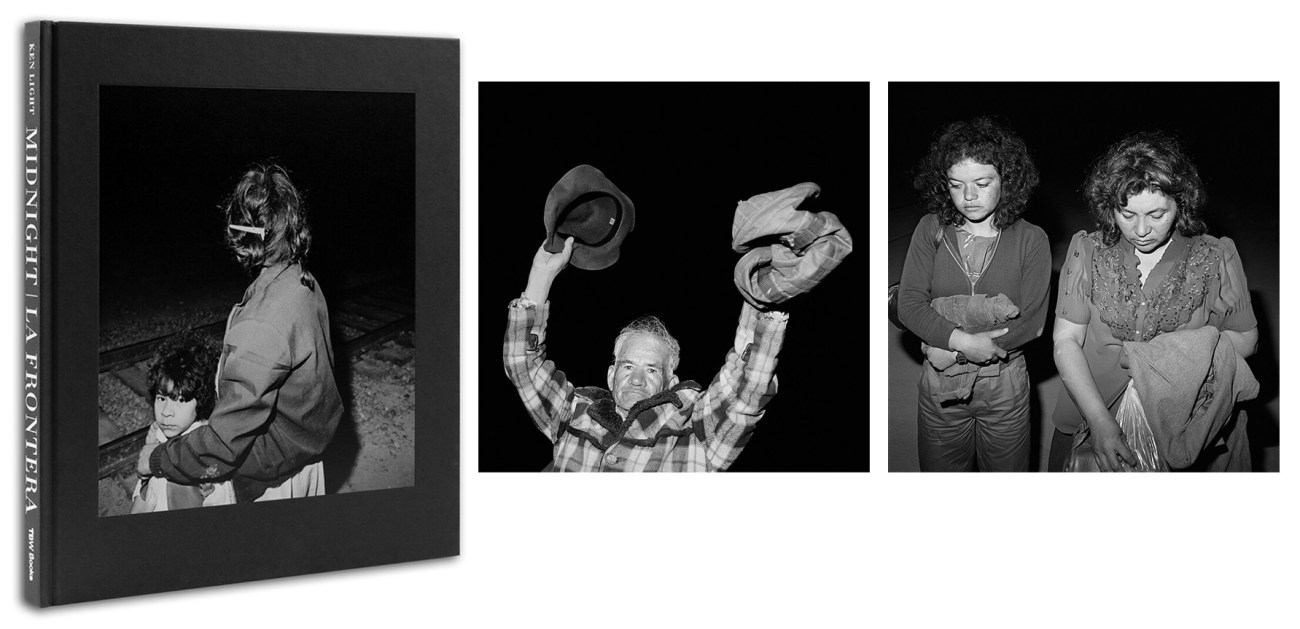

Ken Light — Midnight La Frontera (TBW)

With it’s Weegee-like look (direct flash photos made at night), Ken Light’s latest book has a certain harshness that should make the reader uncomfortable. Light traveled with US Border Patrol through the Otay Mesa in San Diego from 1983-1987, as it looked for people crossing the border. Caught at their most vulnerable—by the agents and by Light’s flash—the subjects of Midnight La Frontera make immediate the fear, desperation, and determination of crossing into the United States. This is reinforced by the introduction of José Ángel Navejas, author of the book Illegal: Reflections of an Undocumented Immigrant, recounting his own attempts (and success) in crossing into the country through this very same stretch of rugged land.

Photographically, it is masterful in the moments and emotions captured. Contextually, particularly in light of hyper-vilification of migrants by Donald Trump, the rawness of some images can be jarring. Yet it’s important to have this unvarnished look at the treatment of immigrants, even if the images are 35 years old. Not too hard to imagine how much worse it’s gotten.

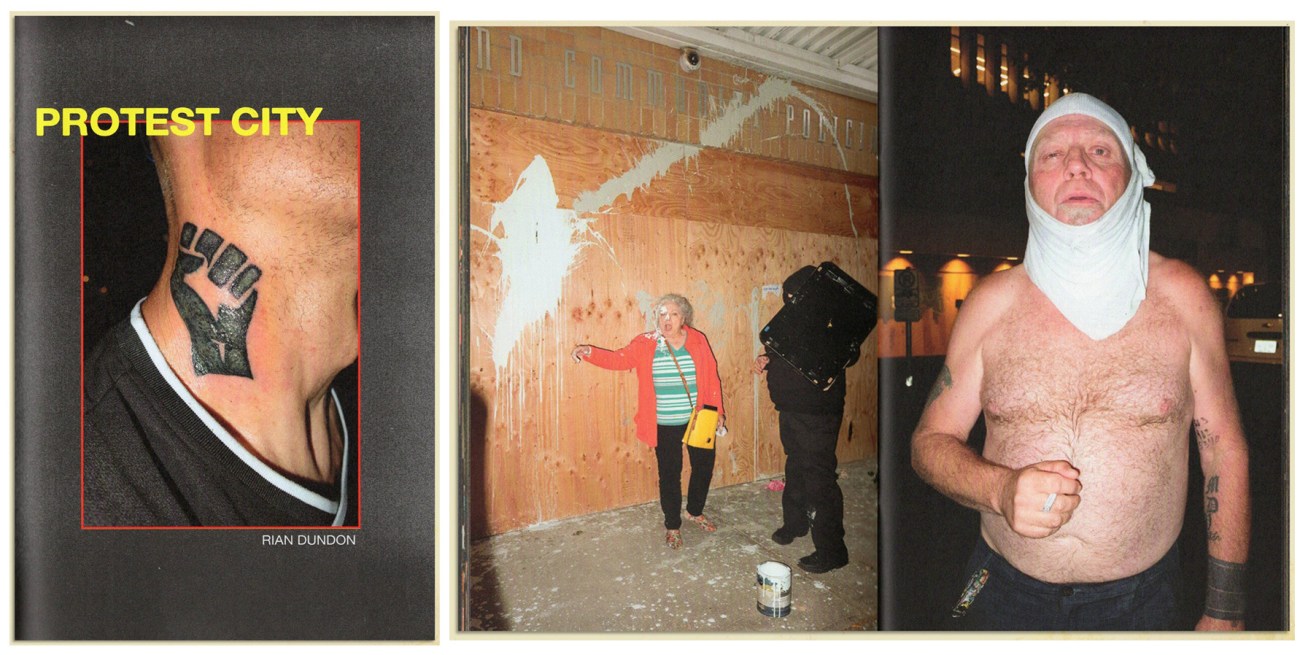

Rian Dundon — Protest City & Protest City 2 (Nighted Life)

From the earliest days of the protests in Portland this year, Rian Dundon was out on the street with a low-key point-and-shoot camera. As the protests dragged on through the summer, Dundon made a point to go out virtually every night to make photos, document the good, bad, and ugly. He put in the work and it shows in these two zines published by Nighted Life. His slightly off-kilter, direct-flash images drag you into the streets alongside antifa, Proud Boys, government agents, police, the media, and just random protesters and curiosity seekers. The result is some of the best protest photography made in a long time. It has a unique voice that fits the moment, rather than trying to recreate the same old tired approach to protests. It actually says something about what is going on, weaving through the tear gas and long guns and livestreamers.

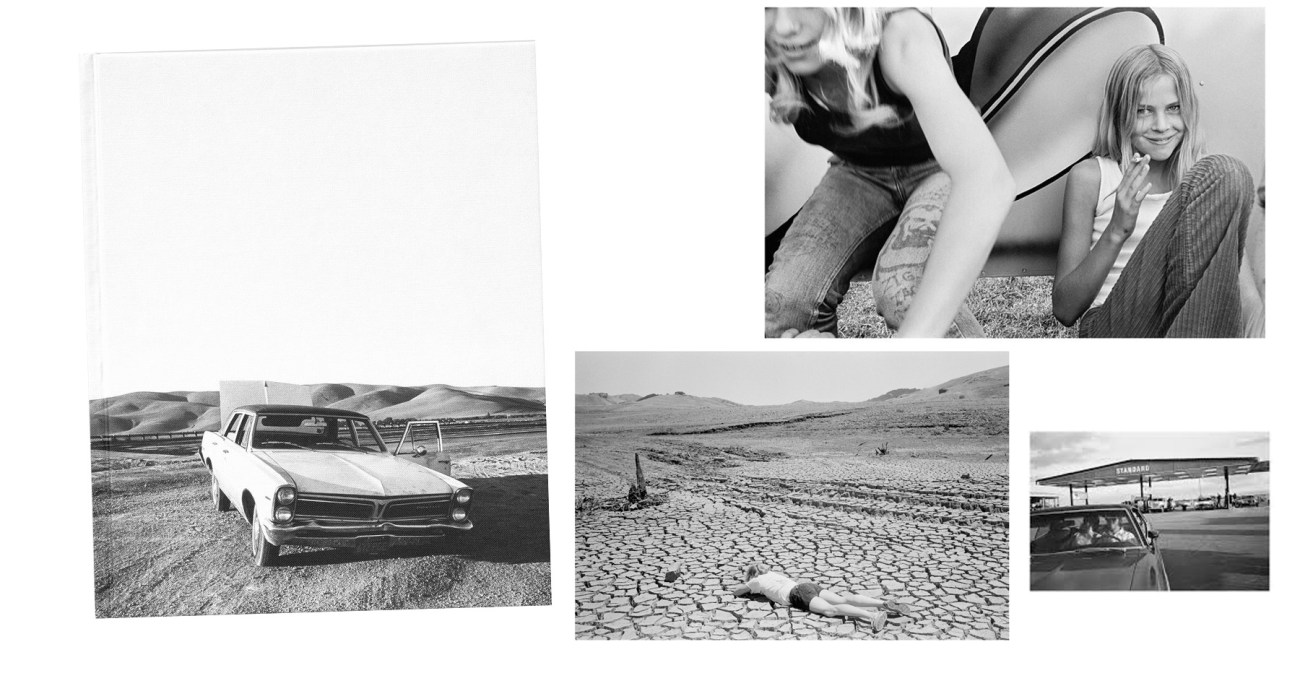

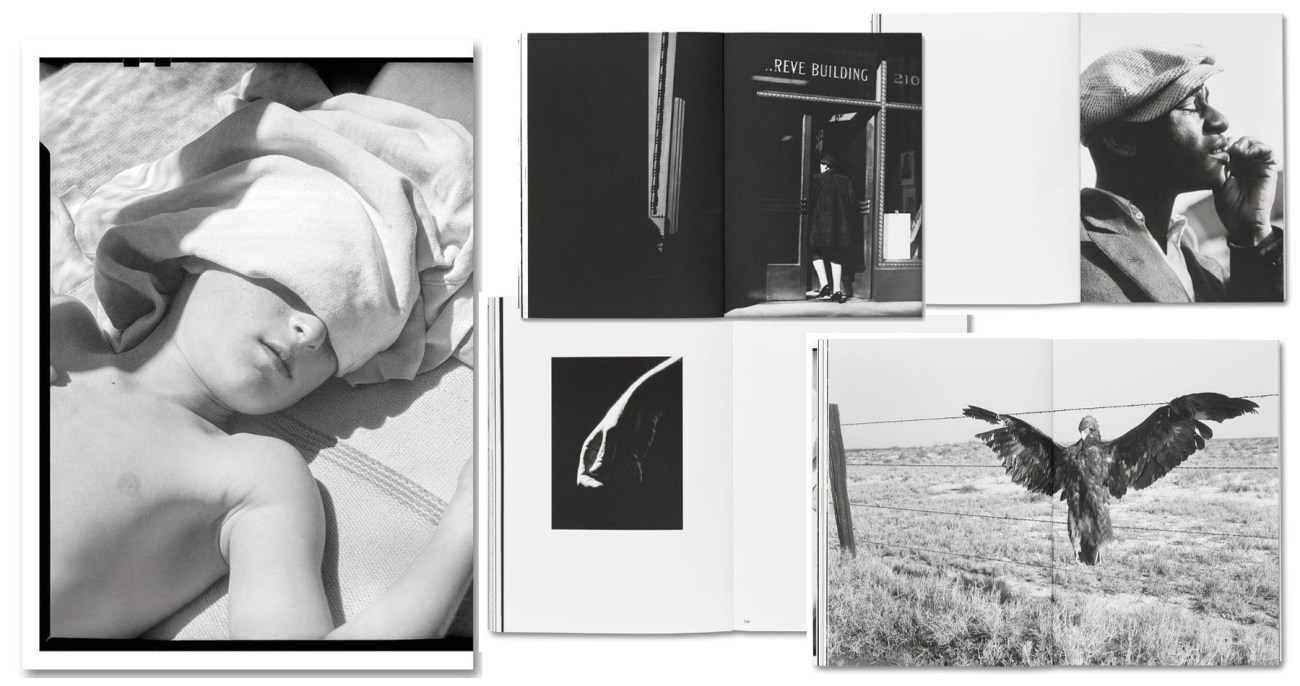

Sam Contis/Dorothea Lange — Day Sleeper (Mack)

In her previous book, Deep Spring, Sam Contis smartly wove her own images with archival photos, playing with ideas around the role of historical photographs, mythologies, and stereotypes. A lot of photographers try this sort of thing, but usually come up short. Contis’ latest book, Day Sleeper, extends this idea by re-editing rarely seen Dorothea Lange photographs shot in California from the 1930s through the early ’60s. It’s one thing to sift through rarely seen archives from a small school, as in Deep Spring. It’s another to plunge into the archives of one of America’s most celebrated photographers and come up with such a pearl. Contis leaned heavily on the “everyday” photos Lange made: photos of her family, street photography she made in San Francisco and Oakland—work made for herself, not on assignment. Despite consisting entirely of photos made 60-90 years ago, Day Sleeper has a thoroughly contemporary feel. Contis’ deft editing and sequencing, balanced around frequent images she found of people sleeping—the “day sleeper”—gives the book a certain feeling of disorientation, a familiar world that feels slightly askew. As familiar as you may feel you are with Lange’s work, this book will make you see her in a whole new, modern light.

Lam Yik Fei — Woh Yuhng (Bronwie)

Landing a number of A1 photos in the New York Times during the 2019 Hong Kong protests, Lam Yik Fei’s dramatic images stood out for capturing the intensity of the protracted street battles, as well as for being so colorful and compositionally smart. Just as the tear gas cleared, Lam got a Kickstarter going for a book that collects his harrowing images of one of the most important moments in Hong Kong’s history.

It’s always interesting seeing how well strong news photos hold up in a different context, such as a book. A series of photos from an event or even a months-long protest don’t always make for a strong, cohesive book; in this case, they do. Lam serves up lots of chaotic moments on the streets, along with a few quiet shots of protesters regrouping, catching their breath. Of course, we know how this moment in history turned out, with protest leaders being jailed or fleeing Hong Kong. That makes this collection a little bittersweet, but still remarkable.