The COVID-19 vaccine rollout is picking up speed: Nearly a quarter of adults have received at least one dose. Better yet, a Pew survey from early March suggests that our confidence in the vaccines is growing: 69 percent of Americans said they had already been vaccinated or were planning to be vaccinated, compared to 60 percent who said they planned to get the shot in a November poll.

That progress is great news—but it’s tenuous. Yesterday, I talked with Baylor College of Medicine vaccine scientist Peter Hotez, who warned that antivaccine activists are looking for any opportunity to erode Americans’ trust in the immunizations. He’s worried that recent hiccups in the rollout of the AstraZeneca vaccine might provide the perfect opportunity for the spread of disinformation.

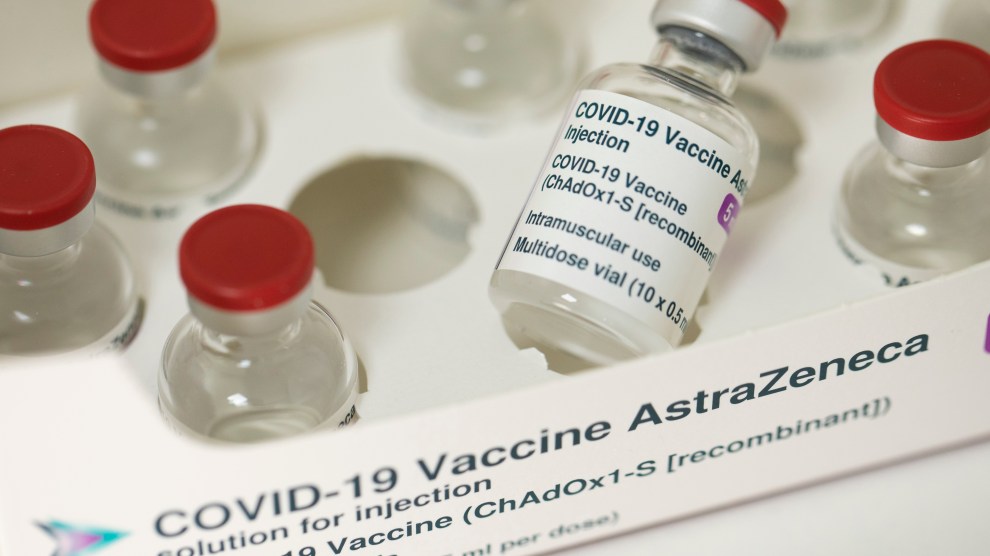

Indeed, the British-Swedish pharmaceutical company has had a rough few weeks. Earlier this month, there were reports of several cases of blood clots in people who had received AstraZeneca’s vaccine, and several countries in Europe suspended its use. Later, European authorities could find no evidence that the cases were related to the shots. Then, earlier this week, an investigation found that the company had used out-of-date data in analyzing how well the shot worked in the United States. On Thursday, the company released new data that confirmed that the shot was 100 percent effective at preventing severe disease and death. The new data showed that the shot was 76 percent effective at preventing mild disease, a drop of 3 percentage points from the initial analysis.

If those setbacks weren’t enough, on Wednesday the New York Times reported that Italian police had found a cache of 29 million AstraZeneca doses in a manufacturing facility. Some observers speculated that the company was hoarding them to ship overseas instead of to other countries in Europe, where vaccine progress has been slow. (The company said the doses were just awaiting quality control.)

None of these problems is a big deal on its own, but taken together, says Hotez, they threaten to tarnish the reputation of the vaccine—and maybe even COVID-19 vaccines in general. “All of that’s cumulative, and it will erode confidence,” Hotez told me.

I’ve been tracking antivaccine sentiment on social media since the beginning of the pandemic, so I decided to do a quick search to see whether the groups I follow have seized on the news around AstraZeneca. Indeed, in just a few short weeks, it’s become a major talking point.

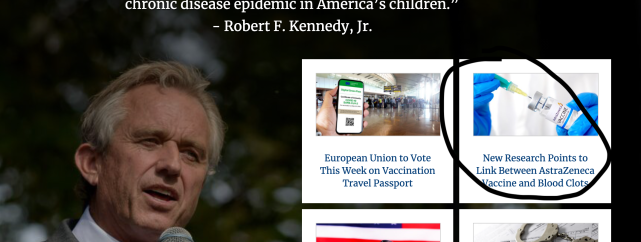

Here it is at Children’s Health Defense, the antivaccine group founded by Robert F. Kennedy Jr.:

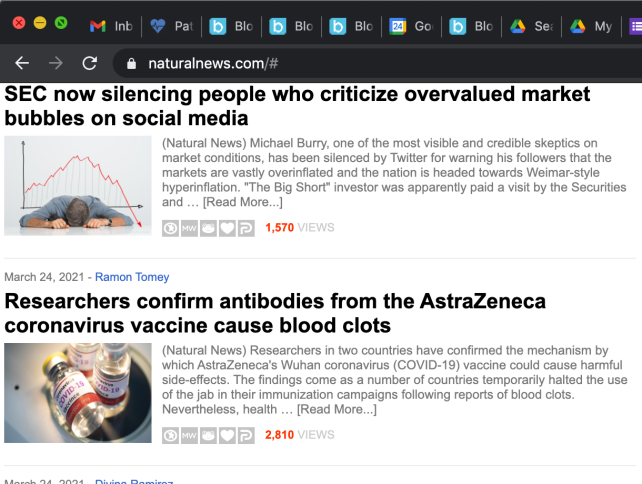

And here’s the far-right website Natural News claiming that researchers have discovered how the vaccine causes blood clots:

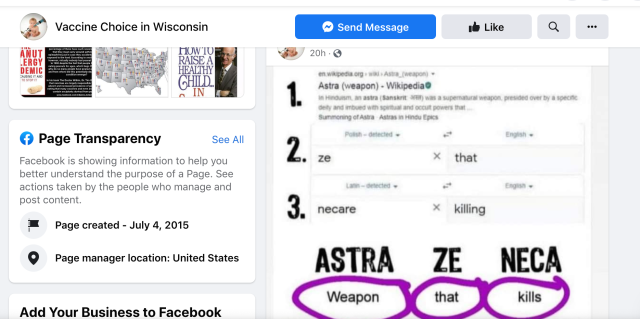

It’s also making the rounds in regional antivaccine groups. Here, a Wisconsin Facebook group claims that the name “AstraZeneca” means “weapon that kills”:

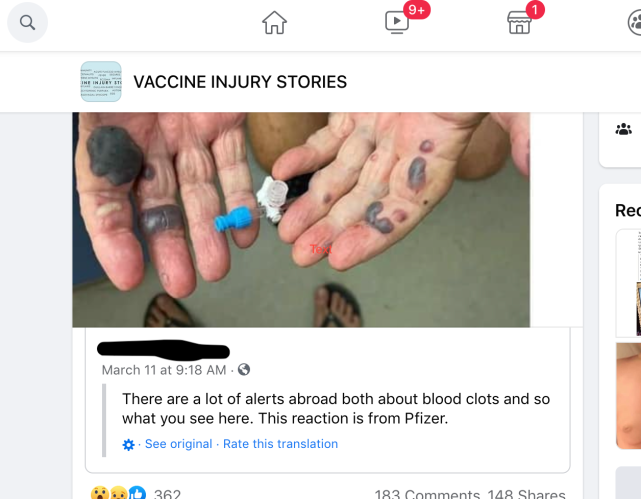

And here’s a Facebook group called Vaccine Injury Stories taking the blood clots story and running with it:

This kind of messaging could certainly sway Americans who are on the fence about getting vaccinated. More worrisome to Hotez, though, are the international implications. In most of the developing world, mRNA vaccines like those from Moderna and Pfizer won’t be available because of their cost and cold storage requirements. AstraZeneca’s vaccine may be one of the only shots available in those regions—and if its reputation is poor, acceptance will be low. “If public confidence is eroding in the United States and Europe, we know what happens—it translates pretty quickly to Africa and Latin America,” says Hotez. “I’m quite worried about this.”

You can watch Peter Hotez’s full remarks here.