Click the highlighted text for more.

One evening in April, Jennifer Sulkess, a 33-year-old filmmaker, was about to order a burger and watch a hockey game at home in New York when she received a WhatsApp message that made her heart race. The message came from Moscow, from a lawyer representing one of her best friends, Anna Fedoseeva. “We need to talk urgently!” the lawyer wrote.

Something terrible has happened, Sulkess thought. She constantly worried about Fedoseeva, ever since her friend had split with her ex-husband, a powerful Russian billionaire named Sergey Grishin. The last time Sulkess received a message from the lawyer like this, two and a half years earlier, Fedoseeva had just been thrown in a Russian jail after Grishin falsely accused her of stealing his money with Sulkess’ help. Both women have been hiding from him ever since.

But the news now was different, Fedoseeva’s lawyer assured her: One of Grishin’s recent personal assistants wanted to speak with Sulkess right away. Sulkess jumped on the phone and listened as the assistant breathlessly listed the reasons she feared they all might be in danger. It’s just a matter of time before this is going to explode, Sulkess recalls her saying.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

Sergey Grishin, 54, has spent more than a decade living on and off in the United States, where he is well-connected. Last August, he made the news when he sold his lavish, 7-acre estate near Santa Barbara, California, to Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. His multiple US-based businesses include a social media company in California with more than 300 million Instagram followers. Called 421 Media, it pumps out viral Instagram content—everything from food porn to photos of nail art—hoping to attract more followers, who attract advertisers like HBO Max and Paramount.

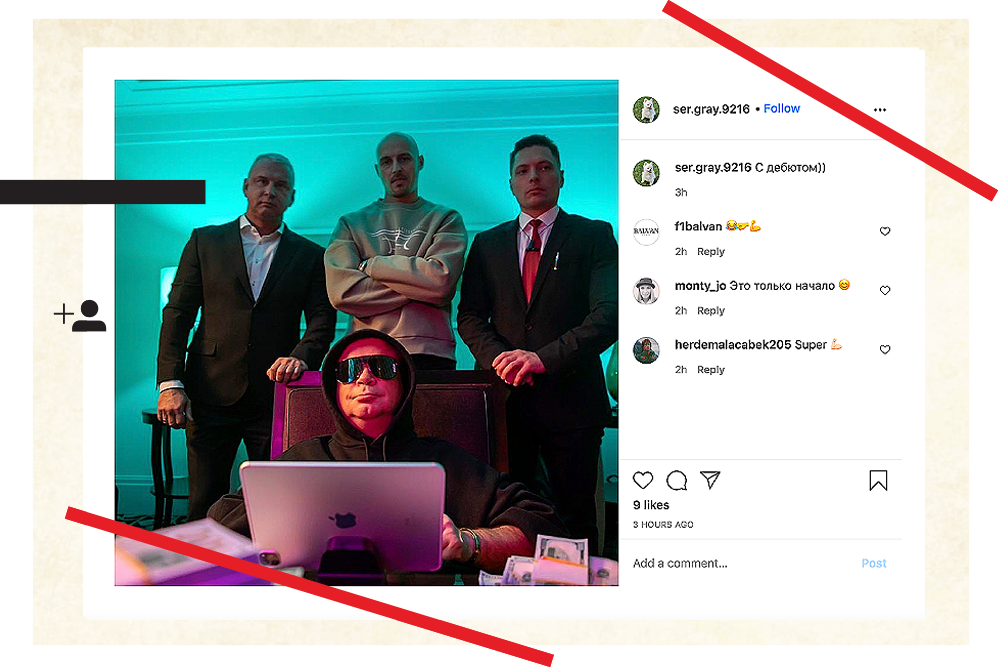

Sergey Grishin, seated, on the set of a music video

Sergey Grishin’s Instagram Account

But the company’s hundreds of millions of followers may not realize that by sharing these viral posts, they’re helping to enrich a man who has been accused in court documents of harassing and abusing Sulkess, Fedoseeva, and other women, sometimes using online channels, including personal Instagram accounts owned by a previous social media company he created.

This article is based on a review of thousands of pages of court records, letters to law enforcement, copies of text messages, and social media posts, as well as interviews with Grishin’s former personal assistant, women who accuse him of harassing and threatening them, and their attorneys. Grishin declined to answer dozens of questions put to him by Mother Jones, but he said through his attorneys that he “denies each of the lurid and sensational claims made against him” by “sources whose credibility is seriously in doubt,” and that he “has never been charged with any crimes because he has not violated the law.” Yet it’s undeniable that women in multiple countries are living in fear of the billionaire. Brushed off by law enforcement, these women have largely been left to fend for themselves.

Minutes after hanging up the phone, Sulkess booked a flight to Los Angeles to meet up with the assistant, Ilona Kevorkian. Within days, I was sitting in front of them in a conference room in San Francisco. It was like something out of a movie. Two women who for years had been on opposite sides of the same nightmare—Sulkess, fighting against Grishin in court, and Kevorkian, who had been paid professionally to cater to his needs—were now coming together to try to expose him.

Sulkess, who keeps her reddish-brown hair pulled into a messy bun, sat beside a large binder she carries whenever she travels, filled with court documents about Grishin and evidence she’s collected. For three years, she has coped with her anxiety about him by spending nearly every waking hour working on her legal cases against him and looking for hints about his next move. On her laptop, she has archived hundreds of screenshots of things that his social media company, 421 Media, has posted on Instagram in case any might hold clues about his plans or prove useful in court.

Sulkess has scoured the binder so many times over the years that she’s practically committed it to memory, able to recall the location of specific quotes within its hundreds of pages. She’s even learning Russian, so she can read the Russian press in case they write about her or Grishin. “I would do this almost as a form of therapy,” she says, flipping through the material, organized meticulously with hand-labeled tabs. She pauses at a photo of Fedoseeva, her teeth cracked and face bloody. “Part of this is to know everything. He tells you what he’s going to do—you have to pay attention.”

On another page, she spots a text message that Grishin sent to Fedoseeva years earlier during their divorce and begins to read it aloud: “When you leave the garage you will suddenly have a flat tire at the exit. You will have to get out of the car. And I will be waiting for you there, with a knife. There are no cameras at that location—I’ve checked.”

She looks up. “He’s premeditated,” she says. “He says, I want you to feel as if you are stuck in a padded room at all times,” she adds, paraphrasing his messages. “Like, You will lose your ability to leave your apartment without fearing that I’m there. It’s a psychological game.”

While Sulkess hunts for clues about Grishin, her friend Anna Fedoseeva has become a recluse in Moscow. She lives in near-constant anxiety that her ex-husband or someone who works for him could find her. Men with long-lens cameras have followed her in the past, so she keeps her blackout curtains shut. She avoids looking at Instagram, afraid of what she might find. “It’s like personal dread,” she says.

It wasn’t always that way. Fedoseeva, 39, grew up in St. Petersburg, a bright, social child with a penchant for fencing. At age 12 she lost contact with her father, a pilot in the military, after he divorced her mother. After finishing her schooling, Fedoseeva opened a Scandinavian design shop in Moscow. But her real dream was to one day work in the film industry.

In 2015, when she was 33 years old, friends set her up with a former banker named Sergey Grishin. Grishin seemed shy, but he charmed her by asking her out to a fancy restaurant and giving her a bouquet. “He was a little nervous, trying to make a good impression,” she recalls. “It was very cute.” Grishin was about 15 years older than Fedoseeva, his belly round and his gait halting because of a past injury and a disease that affected his joints.

She was just getting out of a bad relationship and found him to be attentive and considerate. He took her to Paris and told her she was beautiful, with her long blond hair and blue eyes. He offered to drive her to appointments. “He presented himself like a real man with his actions instead of just words,” she says. She fell quickly in love.

After marrying in 2017, they moved to California, where Grishin had lived on and off for about a decade. One of his mansions near Santa Barbara was famously the location for the crime film Scarface; another, where he first lived with Fedoseeva, had gardens framed by pines and cypresses and a swimming pool, sauna, and tennis court. Soon they moved to Century City in Los Angeles to renovate a penthouse apartment whose neighbors would include Friends actor Matthew Perry and billionaire Vicki Walters, widow of Walmart financier Raul Walters.

Anna Fedoseeva and Grishin at a 2017 birthday dinner in Moscow

Courtesy Anna Fedoseeva

Fedoseeva’s new life seemed like a fairy tale in some ways. But there were a lot of unanswered questions. No one knows how Grishin became a billionaire. The Russian magazine Finans described him in 2008 as “one of the most mysterious bankers in Russia.” He was raised by his mom in a small town near Moscow after his father left them when he was young. Grishin told Fedoseeva that his mom had been controlling during his childhood and that he’d tried to please her and take care of her. But he wanted to be independent as soon as possible. He’s claimed that he started his career in the 1980s by selling homemade cookies for 10 cents apiece from a Moscow apartment. From at least 2010 to 2014, Grishin was, according to court records, the majority owner of Russia’s Rosevrobank, one of several banks around the world that was implicated in an international money-laundering scheme during those years.

Grishin would occasionally fall into dark, unpredictable moods. He was emerging from a turbulent divorce to his second wife when he met Fedoseeva, and he’d been seeking treatment at a “psychological recovery” center because of depression related to the split, according to court documents in Russia. His moodiness seemed to improve after his first date with Fedoseeva. But a few years into their relationship, Fedoseeva would notice sometimes that he was drinking heavily.

Spending all day in his mansions didn’t suit Fedoseeva, either. So close to Hollywood, she dreamed of launching her own company in the movie industry. Soon after she arrived in Los Angeles, a chance encounter with a kindred spirit finally inspired her to make the dream a reality.

At the time, Jennifer Sulkess worked as a personal assistant for actress Kate Bosworth. Like Fedoseeva, she aspired to become a producer and spent her spare time reading scripts, imagining how to bring the words on the page to life. At a bar one night, she struck up a conversation with Fedoseeva, who was new in town and was trying to make friends. Sulkess invited her to a barbecue, and the pair hit it off. “I’ve always gotten along best with people who tell it like it is,” says Sulkess, who thought Fedoseeva seemed easygoing and uninterested in status. Fedoseeva thought Sulkess seemed down to earth, despite her connections to movie stars. They decided to team up and start their own production company. One of their first projects would be a horror flick set in Mississippi about a recovering heroin addict.

As Fedoseeva devoted more time to the film in January 2018, she noticed Grishin becoming irritable. It seemed like her time with other people made him jealous. That month, perhaps curious about her whereabouts in Mississippi, he gained unauthorized access to her password-protected computer and downloaded photos taken during film production, including images of Fedoseeva and Sulkess goofing off, posing for selfies with their heads pressed together and their tongues sticking out. In one shot, they appeared to be lying down together.

After Grishin saw the photos, something snapped. He accused Fedoseeva of having an affair with Sulkess, an allegation Fedoseeva denies. “It was crazy—it was just friendship and a business relationship between us,” she says. While Fedoseeva was on set in Mississippi, Grishin demanded that she return home and sign an oath saying she had never cheated on him or been in love with a woman, and that she would vow “never to pay more time and attention to any person of any gender” than to Grishin.

Jennifer Sulkess (left) and Fedoseeva pose together in San Francisco in 2017.

Court Records

Fedoseeva wondered what had set him off—why had he fixated on her female business partner? Was he becoming impatient with her and looking for a reason to move on? Grishin had entered the relationship with Fedoseeva hoping she would give him children. But one year after their marriage, she had not gotten pregnant. “Sergei did not acquire a family, did not get the family he wanted,” one of his friends later testified in a Russian court.

Fedoseeva signed the oath, but it didn’t placate him. He filed for divorce in February 2018 without telling her, though days later he withdrew the filing. He soon texted Fedoseeva that he would “destroy everything that matters to you.” He emailed Sulkess and other employees of their production company and demanded they quit (though none of them did). He then wrote to Fedoseeva: “All your life and the lives of all your loved ones are at stake now.”

When Sulkess saw the Instagram posts, her body shook with adrenaline. It was March 2018, and she’d been on set when Fedoseeva pulled her aside to show her a strange new account called @annandjen12productions. Fedoseeva believed Grishin had created the account, with the photos he’d hacked from her iCloud account. Beside the images of her and Sulkess, he wrote captions suggesting they stole his money to produce their horror film, an allegation they deny.

“Enjoy the show,” he emailed Fedoseeva, referring to the Instagram account. She watched in horror as her passport and visa information appeared online, along with the oath he’d asked her to sign, on the social media site and on a public website called LoveAndTreason12.com.

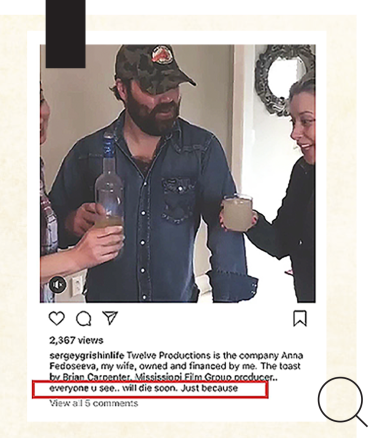

An Instagram post by Sergey Grishin shows a photo of Fedoseeva and a film producer. The caption reads: “everyone u see.. will die soon. Just because”

WhatsApp messages Grishin sent to Fedoseeva’s mother

Court Records

As Sulkess scrolled through the goofy selfies she and Fedoseeva had taken, now posted for the world to see on Instagram, her confusion turned to anger. She had met Grishin only briefly in California before the film project began. “I was pissed that I had to deal with this ‘business’ man in his 50s creating fake Instagram accounts like a 13-year-old,” she recalls. And she worried what his threats might mean for the future of the movie. Fedoseeva, hoping to appease her husband, decided to tell him that she was “releasing” Sulkess from her position on the film.

But the maneuver didn’t work. That month, Grishin sent Sulkess an ominous email stating that he was her “best friend.” Sometimes, he wrote, “friends” can be “cruel, merciless, smart devils who can wait for many years.”

Grishin’s relationship with Fedoseeva continued to splinter. In late March 2018, he refiled for divorce and began building a legal case, which he would later lose, claiming that Fedoseeva married him for his money, which she denies. He hired a team of big-shot attorneys and suggested he had other impressive connections: Days before filing for divorce, he told Fedoseeva he would reach out to then–President Donald Trump to request US citizenship. In May, Grishin sued Fedoseeva’s production company, accusing her and Sulkess of fraudulently accepting money from him for their film and refusing to pay it back, an allegation they deny.

As he attempted to shut down the women’s film company, Grishin was planning his own new venture. That month, he launched a social media company called Sergey Grishin Enterprises with the goal of buying popular Instagram accounts and amassing followers.

The new project seemed to do little to distract him from his jealousy of Fedoseeva. He texted her increasingly violent messages in Russian, saying that he owned a Glock with a 15-round clip. In another message, he envisioned killing her at a Four Seasons hotel and broadcasting the death on YouTube. He said that “at the right moment,” he would turn his social media capabilities “into a weapon…against you.”

“You tell me what pictures you like,” he later added in Russian as he detailed a plan to post more photos of her online. He noted that his company would amass 10 million followers.

Sulkess urged Fedoseeva to stop replying to her husband’s text messages, hoping he might calm down. But Fedoseeva worried her silence might make him feel rejected and enrage him further. Though the threats nauseated her, Fedoseeva decided it was in her best interest to keep the channels of communication open. Make sure to document everything, Sulkess told her.

As Grishin told Fedoseeva about his new business, Fedoseeva began to pry more information from him, trying to learn how he might use it against her. “I just don’t understand what the company will do?” she wrote to him. He responded bluntly: “Content first, increasing the number of subscribers, recruiting an audience. And then the hidden manipulation of people to encourage them to do certain things. But good things for them as well as the world.” He explained that he planned to hire four young hackers in Florida and open an office in Moscow, and that he wanted to use the business in part to promote himself. “Yes, I want to be the most powerful man in the world,” he wrote to her days later. He added that he hoped to expand eventually from Instagram to Twitter, noting that the platform was actively used by Trump, who’s “heard everywhere.”

“He threatened that he’s going to use all the followers and put in their minds everything he wants to see,” Fedoseeva tells me. “It’s like an army—his army.”

One of Grishin’s favorite books is The Master and Margarita, a classic Russian satirical novel by Mikhail Bulgakov about a satanic figure who arrives in Moscow disguised as a foreign professor named Woland. Dressed in a black cloak, with different colored eyes, Woland is portrayed as both manipulative and honorable, merciless and generous. He aims to publicly expose the worst qualities in people.

Grishin, in conversations with women, occasionally declared that he had three personalities: Sometimes he acted like a businessman; sometimes he was more like a little boy, gentle and innocent; and sometimes, according to court documents, he likened himself to the demonic Woland. On June 1, 2018, still pursuing a divorce from Fedoseeva, he let that third side of him come through, telling her in a text that she was like a “poisonous reptile.” “I will simply punish you by cutting you up piece by piece from the tail. Until I reach your head,” he wrote.

Then, a couple of days later, his mood seemed to flip again. He asked Fedoseeva to meet him at his apartment in Moscow. He said he was no longer angry and he wanted to resolve their differences. Though Sulkess begged her not to go, Fedoseeva agreed to visit him after he assured her a third party would be present.

But when she arrived on June 3, it was just the two of them. When Fedoseeva describes to me what happens next, her voice grows quiet. “Sorry, it’s difficult,” she says. “I was in shock.”

According to a complaint she later filed in a California court, once she was inside the apartment, Grishin pointed a gun with a silencer at her. He instructed her to walk to the corner of the room and strip naked, and he said he was about to kill her. As she began to remove her pants, he allegedly said he had planned everything and would make it look as if she had attacked him with a knife. She quickly reached for the gun’s silencer and wrestled it to the floor, where they began to struggle. He punched her in the face and head-butted her. Finally, she opened the door and ran to a nearby apartment, where she called the police. Medics took her to a hospital and treated her injured nose, lip, and cracked teeth.

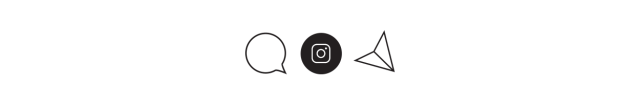

A photo Fedoseeva took of herself after the scuffle with Grishin in 2018

Court Records

But whether they lacked a witness or were simply ambivalent, the Russian police did not pursue the case. “His aggression skyrocketed from that moment,” Sulkess recalls. When Fedoseeva got home from the hospital that night, she showered the blood off her body and then called Sulkess, terrified, before trying to sleep. Three hours after the attack, Grishin went online and posted a photo on Instagram of a woman in an elegant black dress standing on a mountain, with the caption, “Chilling on top of the world!” The next day, he texted Fedoseeva several messages, telling her that a doctor could give her a “new Hollywood smile.” “Shall I redo your hair? It’s all over the place! Make yourself a chignon!” he added in Russian.

He continued to mock her in the coming days, sending dozens of messages threatening Fedoseeva and her family. “I will come. Wait in fear,” he texted in Russian. “She is not pretty anymore. Missing some teeth,” he added the next day in a WhatsApp message to Sulkess, who also began documenting all the threatening messages she continued to receive from him as she processed her own emotions. “There’s a rage, like, Who the fuck are you that you can do this to people?” Sulkess says. “And there’s a fear as well: Is anyone ever gonna hold this person accountable?”

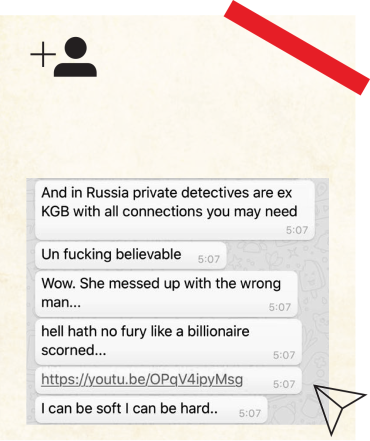

Sulkess and Fedoseeva successfully sought temporary restraining orders from the Los Angeles Superior Court, citing the attack and the threatening messages. Grishin filed for and got one, too, claiming Fedoseeva was the aggressor in the fight and had left him with head trauma. “She messed up with the wrong man,” Grishin wrote to Fedoseeva’s mom on WhatsApp two days after they received the restraining orders; “hell hath no fury like a billionaire scorned.” (Neither Grishin nor Fedoseeva faced criminal charges related to the attack, and Grishin’s restraining order on Fedoseeva expired three months later when he failed to pursue it.)

Meanwhile, Grishin had become engaged to a new woman, Ekaterina Loginova, after dating her for about two weeks. In California, Loginova noticed that he was becoming “obsessed with his ex-wife and discussed daily his plans to get revenge against her,” according to letters that Loginova’s attorney later wrote to the Los Angeles police. “When Ms. Loginova pleaded with Mr. Grishin to calm down and abandon his plans for revenge, he became violent and threw a recorder at her.”

On June 15, Loginova packed a suitcase with all her clothes and returned to Moscow, saying she needed to see her physician. The next day, according to her attorney, Grishin sent her dozens of threatening video messages. In one, he stood in front of the camera with his genitals exposed, ranting about his “enemies” and calling himself “the devil.” In another, he broke a framed photograph with their image inside, shattering the glass.

In the early hours of the following morning, Grishin sent Loginova a video in which he accused her of stealing money from his safe and threatened to report her to the police—echoing allegations he’d filed around the same time against Fedoseeva and several other women, including an employee who had worked for him for 25 years. He also accused her of having a romantic relationship with Fedoseeva, whom she had never met. Grishin boarded a plane to Moscow, but Loginova refused to see him. “The devil will rise and he will render his justice,” he texted her. Loginova hardly left her home for six months after that and had trouble falling asleep at night.

Grishin and his former fiancée, Ekaterina Loginova, in April 2018

Court Records

As Grishin focused on Loginova, Fedoseeva and Sulkess hoped his harassment of them might stop. Their temporary restraining orders prohibited him from threatening or contacting them and instructed him to surrender all his weapons. But, according to court records, the day after the orders were issued, on June 20, one of Grishin’s business associates sent the two women messages on Grishin’s behalf, including a link to an Instagram video of a man wielding a large knife and chopping things.

Around this time, Fedoseeva moved into Sulkess’ apartment in Los Angeles. She started having panic attacks and felt anxious going out in public. During an outing to Universal Studios with a friend, she looked down at her phone, saw a text from Grishin, and then struggled to breathe. She told her friend she needed to be alone. Every time she or Sulkess returned home, they checked their closets and bathrooms to make sure an intruder sent by Grishin wasn’t there. “I was so scared that he was going to hurt me, hurt my mom, and hurt my friends,” Fedoseeva recalls. “He would send hundreds of messages to all of my phones, so you can never escape him. I felt like I was underwater with no air.”

Fedoseeva’s mother, back in St. Petersburg, wasn’t safe from the harassment either. Grishin suggested to her that he had access to assassins who could kill her daughter whenever he pleased. “I will make her be tortured before your eyes, she will die with time, not instantly,” he wrote to her in Russian. In July 2018, according to court documents, he sent Fedoseeva’s mother a message with an attached audio recording of himself attempting to hire a hit man, admitting he had 16 people on his list. “Lucifer will find people to assist him,” he said in Russian in the recording, after noting that he had some of the devil “living inside” him. “I want some people to disappear and some to be made examples of. And that’s that.”

He made it known that he was a man who could get what he wanted. At one point in the recorded conversation he alluded to the photographs he’d found of Fedoseeva and Sulkess. “How did you discover these?” the person he was speaking with asked him in Russian, according to a translation. “Agentes secretos,” he replied. “Did you hack into her account or what?” the other person asked him. “These were her photographs. She had them made…So, I started investigating further,” he said.

Throughout the conversation, he appeared to be talking about his connections to Russian mob bosses. The same month he sent the recording to Fedoseeva’s mother, he hinted at some of these mob relationships again: On Instagram, he posted two videos of himself on a private jet, claiming to have orchestrated what he described as one of the largest bank crimes in Russian history in the 1990s. “That’s a good story to tell to someone: how a single person like me can create a system that almost caused the collapse of the Russian banking system,” he said, his arms crossed. He added that he could reveal who else was involved in the financial crimes.

Grishin also boasted in one of the videos that he owned a social media company, and said he was sharing the videos because Russian criminals and government officials were now after him. Sulkess later wondered whether he found some measure of safety in the company’s large Instagram following, or whether he meant to imply that he could expose the Russian mob bosses online. The same month he posted the videos, he emailed his business associates at Sergey Grishin Enterprises and urged them to buy more Instagram accounts, “the best accounts possible,” with a goal of reaching 300 million followers over the next few weeks.

But it wasn’t Russian criminals he targeted on Instagram—it was Fedoseeva and Sulkess. The company’s accounts began directing followers to at least one of Grishin’s personal accounts, which featured his disparaging posts about the two women; the company’s accounts also said people who followed him would have a chance of winning millions of dollars. Grishin regularly updated Fedoseeva about his growing number of followers, according to text messages submitted in court. And despite the temporary restraining orders, he posted several images on Instagram of Fedoseeva, including one with the caption, “My wife Anna Fedoseeva and her friend Jennifer Sulkess [heart emoji] fuck u in the ass with cactus!” Another post showed a video of Fedoseeva giving a toast with some of her business associates, with a caption that said, “everyone u see.. will die soon. Just because.”

“Regardless of his Instagram usage, Mr. Grishin is engaged in direct, almost gleeful violation of the Temporary Restraining Orders,” the women’s attorney wrote to the court. “He seems to delight in sending horrifying messages to Ms. Fedoseeva and Ms. Sulkess, day after day.”

On August 2, 2018, the court ordered Grishin to suspend all his personal Instagram accounts and other social media accounts, including some allegedly owned by Sergey Grishin Enterprises. According to court records, he left the accounts active for several days—his attorneys say he was in a hospital and couldn’t take them down immediately—and then changed the name of one account, kept it up, and posted videos boasting about violating the court’s orders. For days, he continued sharing videos on Instagram depicting knives and assault rifles. He finally shut down the account around August 22, the day he had to file a document with the court.

By this time, Sulkess and Fedoseeva had little hope the restraining orders would save them. “Every time they step outside, they have to wonder if this is the time that Mr. Grishin will come and attack them…Every time they drive their cars, they check to see if they are being followed,” their attorney wrote to the court later. Fedoseeva had earlier found security footage that showed three men planting and retrieving surveillance devices outside a friend’s Moscow apartment where she was staying; her attorney suggested in court that the devices may have been installed as part of Grishin’s attempt to stalk Fedoseeva.

Grishin pushed back against that narrative. In a declaration to the court, he accused Fedoseeva of being the aggressor during their physical fight in Russia, though he never filed a police report about it. He did acknowledge sending inappropriate messages to her, her mother, and Sulkess over the spring and summer, including after the restraining orders were issued, but blamed his deteriorating mental health and noted that he was hospitalized in Los Angeles in late July.

“I was operating at far less than my normal mental capacity…In retrospect, I realize that during the time period in which I was unable to sleep for days at a time, I was easily moved to emotion, fear, and extreme anxiety,” he told the court. He apologized and said he could hardly remember sending the messages, “because these actions took place in what I can only describe as a ‘fog’…[M]any of them are completely nonsensical, and devoid of anything approaching a ‘threat.’” One of his business associates and friends, Tim Pinkevich, a partner at Sergey Grishin Enterprises, testified that he witnessed Grishin’s depression get so bad that he couldn’t rise from the couch. Grishin added that his medication levels had since been adjusted and he was doing better.

But a few months later, instead of leaving Fedoseeva alone, he only ramped up his attacks on her.

Fedoseeva returned to Russia for divorce proceedings in November 2018. She suspected she was being watched. The following details about her experience in Moscow are drawn from court records. While she was in the city, Grishin filed a report with the Russian police accusing her of swindling money from him during their marriage. The authorities found her at a friend’s house and threw her in jail, arguing that she might flee during the investigation otherwise.

Fedoseeva was terrified, because Grishin had previously told her that her death would come one day in prison. The moment when Sulkess learned Fedoseeva was jailed, she says, “was the scariest moment in my life.” She called another friend and begged her to stay on the phone, saying she couldn’t catch her breath.

After 10 days, Russian authorities released Fedoseeva from jail. They did not pursue charges against her and determined that her arrest had been illegal. She was awarded 35,000 rubles (about $500) in compensation for the false imprisonment, according to US court records. The Russian press reported that Grishin had bribed authorities to have her imprisoned, an allegation one of his attorneys denied as propaganda during a court hearing. No charges were ever filed against him, but Fedoseeva accused him in a US court of filing a false police report against her.

Back in California, Sulkess was having nightmares, panic attacks, and even stress-induced seizures after the jailing. She was afraid to spend too much time with friends; she worried that Grishin might target them, too.

This fear wasn’t unfounded. Sulkess’ friend Staci Witt, a makeup artist, would later be named by Fedoseeva’s legal team as a character witness. Weeks after Witt agreed in September 2019 to testify, she was hiking in Arizona when a string of bullets flew over her head, so close that she could hear them whistling. Another time, a couple of weeks before her deposition in February 2020, a man in a gold car came to Witt’s house near Los Angeles and pointed his fingers at her like a gun. She filed a police report after both incidents and started having panic attacks. Witt couldn’t prove that the two incidents were related to Grishin but wondered in her deposition whether he or his associates were involved.

Around this time, Fedoseeva and Sulkess were trying to get help from the Los Angeles Police Department. They’d filed a police report in 2018 about the restraining order violations and the harassment and later updated the detective about the Russian jailing. But in late 2018 or early 2019, the detective dropped the case. “They were not interested in credible death threats,” Sulkess told me. (The LAPD declined to comment, citing privacy concerns. A spokesperson for the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office said prosecutors reviewed the case in 2018 and found there was insufficient evidence to pursue a criminal charge. The police report had been filed before Fedoseeva’s mother discovered the audio recording of Grishin seeking a hit man; Sulkess says she later updated the detective about that piece of evidence, to no avail.)

“They decided it’s not a case,” Fedoseeva tells me over the phone, adding sarcastically, “Just maybe you can come back when he kills you.”

As the pandemic began in early 2020, Sulkess discovered that Grishin’s social media empire was still growing. She was researching Grishin on her computer when she came upon a California secretary of state filing that listed Grishin as co-owner of a company called 421.

The company’s reach was massive. It had hundreds of millions of followers, about the same as Beyoncé and Taylor Swift combined, and was making waves in the industry. In September 2019, the Wall Street Journal profiled 421 Media for a piece about “meme factories…reshaping how Instagram content is made.” The article, which did not mention Grishin, described how 421 Media staffers, many of them small-time Instagram celebrities, work behind their laptops at their Venice Beach headquarters to create viral posts interspersed with plugs for brands like Red Bull, Popeyes, Black Rifle Coffee Company, and TikTok, as well as the NRA and celebrities like Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion. The company claims to reach 750 million users monthly across 125 Instagram channels, attracting advertisers including HBO Max, Paramount, Atlantic Records, MTV, Discovery Channel, and MyPillow. Gregg Colvin, the company’s co-CEO, told the Journal, “Our goal is to advertise at the highest level.”

The content created by 421 Media is mostly innocuous clickbait—lots of memes, food porn, photos of nail art, and musings about romance. But some of it is far more sinister. After a mob of Trump supporters stormed the US Capitol in January 2021, Sulkess noticed that one of the company’s Instagram channels posted videos of the insurrectionists, captioning each one with the statement, “WE THE PEOPLE ARE PISSED! What are your thoughts?”

Sulkess, weary from two years of thinking about Grishin, got a second wind when she discovered his connection to the company. Every morning for weeks she would wake up, pour some coffee, light a cigarette, and begin checking 421 Media’s Instagram accounts, making copies of posts that seemed odd or troubling to her. One of the images showed a woman’s naked torso with a shadow of a gun hovering over it and the words “Yes, boss” superimposed across her skin. Most days she worked for 8 to 12 hours, clicking through post after post in search of clues about Grishin’s next move. The memes she saved ranged from politically inflammatory to borderline pornographic to downright menacing.

“For me, it’s important to see everything so that I can stay a step ahead,” she says. “After Sergey had Anna arrested in 2018, I told myself that I would never be blindsided by Sergey or his enablers again.”

Grishin’s name, Sulkess quickly realized, wasn’t listed anywhere on the company’s website. She wondered if that was intentional. She knew that back in 2018, before 421 Media even existed, the court issuing her restraining order made it harder for Grishin to operate his previous social media company, Sergey Grishin Enterprises, by forcing him to suspend his personal Instagram accounts and some accounts owned by that company. At the time, Grishin pushed back: He assured the judge that SGE would not harm Fedoseeva or Sulkess and pledged that two of his senior executives, Dovi Frances and Roni Eshel, would henceforth control what content was posted on its Instagram channels. One of Grishin’s attorneys argued that if the court forced him to deactivate the company’s accounts, it would harm other employees who had nothing to do with the harassment. The judge didn’t buy it and ordered him to get rid of some of the company’s Instagram accounts.

A few months later, in December 2018, Grishin helped launch 421 Media, according to filings with California’s secretary of state. The new company was led by Frances and Eshel and at least one other high-ranking employee from Sergey Grishin Enterprises, and it absorbed at least two or three dozen of the same Instagram accounts.

Though Grishin’s name appears nowhere on the company’s public website, it seems he was involved behind the scenes. His previous firm, Sergey Grishin Enterprises, trademarked the name of the 421 Media company, and both businesses have the same mailing address. What’s more, the 421 Media website is hosted from the same IP address as the website that Grishin created in 2018 to publicly post photos of Fedoseeva and Sulkess and their private information. At least one of the company’s Instagram channels still maintains old posts directing people to Grishin’s now-defunct personal Instagram accounts, offering new followers a chance to win millions of dollars. In a court statement in May 2021, 421 Media was described by its chief operating officer as “one of Grishin’s companies.”

Yet it’s unclear the extent to which Grishin is involved in the company’s operations. He’s often traveling outside the United States and was reportedly pursuing new business ventures in Russia recently, including with the development firm Malltech, which is partly owned by Goldman Sachs.

Shortly after Sulkess served a deposition subpoena on a 421 Media financier and one of the company’s executives, she received a strange request from an Instagram account seeking to follow her on the platform, which would allow the account to see more of her information. It belonged to 421 Media. “Grishin’s message to Sulkess through his attempted cyberstalking is loud and clear,” her attorney wrote in a court filing in September.

As of April, 421 Media executives were in negotiations to sell their company to one of at least two possible buyers, including Maven Media, the publisher of Sports Illustrated. 421 Media did not respond to my list of questions.

Even if the company is sold, Fedoseeva and Sulkess still worry about what Grishin might do. “He is watching her every move,” their attorney wrote in the court filing, “which is a reminder that he has the means and the desire to wait for years to implement his plans.”

After months without hearing from Grishin, Sulkess in April got the phone call from Grishin’s former assistant, Ilona Kevorkian. He’s like a walking bomb, Sulkess recalls her saying.

Born in Russia, Kevorkian, 44, had come to the United States as a teen and moved to California in 2018 looking for a change after years working in law enforcement. Through a temp agency she found an administrative job with one of Grishin’s financial services companies, SG LLC. She worked hard to prove herself as dependable, and she was eventually promoted to a role at another company, SG Acquisitions, that functioned like Grishin’s personal assistant, traveling with him and making sure his needs were met.

At first she was glad to have the job, but there were some red flags. When she had to help Grishin move from one luxurious condo to another in Los Angeles, she says she found small holes in the walls with bullets stuck in them. She was alarmed but she tried to brush it off. Grishin denies this incident.

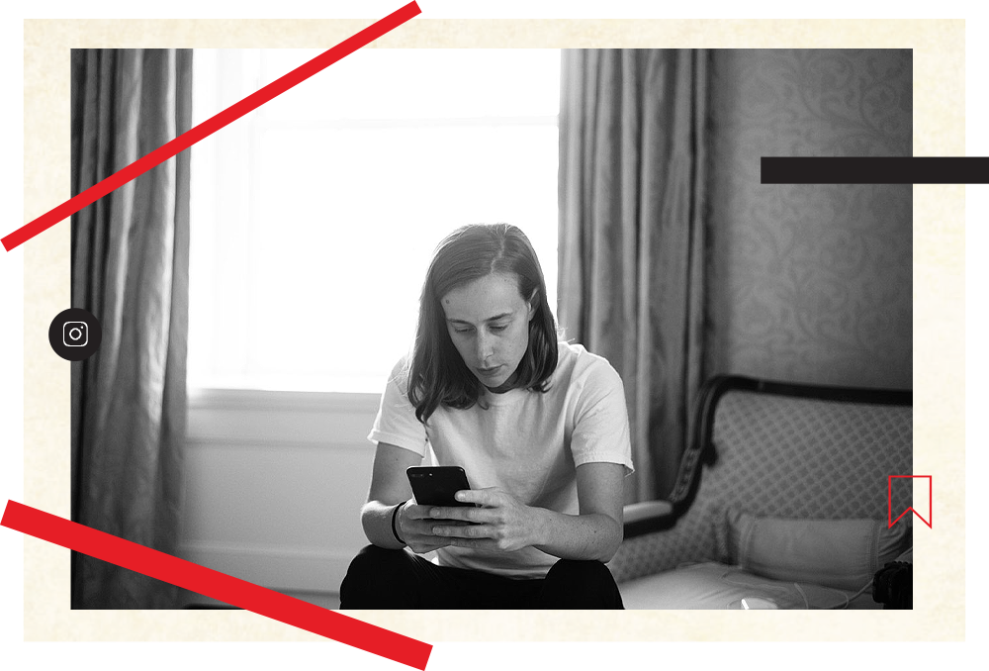

Sulkess in 2017

Courtesy Jennifer Sulkess

Soon she learned about Grishin’s network of escorts, some of whom he has traveled with in the United States, Russia, Dubai, Mexico, Jamaica, and other countries. Sometimes Kevorkian helped organize their passports and other documents, noticing that most of the women, who are mentioned in court records, said they were between the ages of 19 and 25. Grishin called them his girlfriends but compensated them for their services.

In March 2020, Kevorkian flew to Jamaica on a chartered flight to assist Grishin and a 23-year-old escort named Nadezhda Liventseva, who were staying there. It was Kevorkian’s first trip with the billionaire, and she was surprised to find him often intoxicated on Dom Pérignon. His mental health seemed to be deteriorating. One morning she went to make herself coffee and saw feces smeared all over the kitchen, leading up the carpeted stairs to Grishin’s bedroom. A similar thing happened on multiple occasions. When the villa staff refused to clean up the mess, Kevorkian put on gloves to strip the beds herself and pick excrement off the floor.

Another day, a butler came to fix the broken air conditioner. Grishin, upset about what he considered to be poor service, turned to Kevorkian with a smile. I want to punish him, she recalls him saying, unsure if he was joking. Let’s tie him up and shove something in his rectum. (The butler left, unharmed.) Grishin also allegedly asked her to watch with him while Liventseva stripped and danced. “I think he was playing psychological games to see whether I would comply or if I would break down,” she says. One morning he sent back the eggs that a chef had prepared and asked her to make a fresh batch that were cooked for exactly seven minutes.

Kevorkian stayed because she wanted to build her career. And she felt sorry for Grishin. She noticed he was not taking his medication, and she tried, sometimes successfully, to get him to stop drinking so much alcohol, worried he might hurt himself. “I viewed him as a victim,” she adds.

As they spent more time together, Kevorkian heard Grishin talk about Fedoseeva and Sulkess. He said he no longer loved Fedoseeva, but Kevorkian perceived that it still pained him to talk about his ex-wife, because he appeared uneasy or even angry whenever her name came up.

Kevorkian’s job gave her a behind-the-scenes look at Grishin’s legal fight against the two women, according to court documents. She got the impression that his lawyers were trying to ruin Sulkess and Fedoseeva financially: One time, she says, she asked Grishin’s attorney Amman Khan why Grishin was spending more on a lawsuit over the marriage contract than he stood to recover, and Khan responded that the goal was to defund Sulkess and Fedoseeva so the two women couldn’t fight anymore. (Khan did not respond to a question from Mother Jones about this interaction but suggested that Kevorkian had misrepresented other conversations he’d had with her in the past.)

Kevorkian saw evidence of other menacing tactics: From late 2018 to mid 2020, according to court documents, Grishin’s associates allegedly hacked into a US phone that Sulkess gave to Fedoseeva, and copied private conversations between Fedoseeva and her attorney about the US lawsuits with Grishin, a violation of privileged attorney-client communications that would constitute a federal crime. (Grishin and his attorneys contest this allegation.)

Though Grishin told Kevorkian he’s moved on from Fedoseeva, Kevorkian worries about Fedoseeva’s safety. “Given an opportunity, if he ran into her, I think the possibility is very high that he would do something to her,” she says, echoing comments she made to a court.

Some of the escorts have reason to fear Grishin, too, she says. In November 2020, Russian media reported that he was trying to jail another one of his escorts, the 23-year-old Nadezhda Liventseva who traveled with him in Jamaica, after he accused her of stealing money from his desk drawer, according to the REN TV channel. Kevorkian does not believe these accusations are true and says Liventseva went into hiding in the Middle East.

One of Grishin’s other escorts, according to Kevorkian, is Anastasia Vashukevich (a.k.a. Nastya Rybka), a well-known model and author of The Billionaire Seduction Diary who made headlines in 2018 when she claimed to have evidence of Russian interference in the 2016 Trump election. (The evidence never materialized.) Leading up to the election, she claimed to be in a romantic relationship with Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, a Putin ally who was later accused by a Russian opposition leader of relaying information to the Kremlin about the Trump campaign that he’d allegedly obtained from Paul Manafort. (Deripaska called these allegations “outrageous and false.”)

In a series of texts to me, Rybka seemed reluctant to talk. She denied being Grishin’s escort and said she didn’t know him well and was not afraid of him. His Instagram account shows many recent photos of her, including a few of the two of them together.

Today, Kevorkian is concerned for Rybka as well. She showed Mother Jones a text message that Grishin wrote about Rybka and sent to Kevorkian in Russian in March, saying that Rybka was still alive but implying that perhaps it would not be the case for much longer.

In January 2021, Rybka went on Instagram and shared a “behind the scenes” promotional clip for a music video starring her. Grishin is also featured in the clip, seated at a laptop wearing dark sunglasses and no pants as a woman kneels at his feet under the desk. Later in the video, he tosses paper money on Rybka’s torso while she lies in a bathtub. “The truth of making music video [smiley face emoji],” he wrote in a caption on Instagram accompanying the clip.

To Sulkess, his comment seemed like a not-so-veiled jab at her and Fedoseeva, who produced a music video together as their first project in 2018. “He does not discriminate when it comes to threatening people, but it’s mostly aimed at women and people he deems weaker than he is,” says Sulkess. “He’s got an infinite amount of money. That’s the core of it.”

After Kevorkian complained about her working conditions to human resources, SG Acquisitions shut off her access to email and locked her out of her office, firing her a couple of weeks later. (Kevorkian believes she was terminated in retaliation for her complaints; her boss Tim Pinkevich says the company let her go after learning she kept a gun in her office, which she says they discovered after locking her out of the room. She says she had the gun from her law enforcement days and she thought storing it in her office’s double-locked drawer was the safest option.)

Though she can no longer keep an eye on Grishin, Kevorkian thinks back on his threats, on all the evidence of his troubled mental state, and worries he is an imminent danger to himself and others. She says she felt morally obligated to speak out. “I’m telling you, there is no middle with this guy,” she says. “I either saw a little boy who was sitting there being silly, or it was Woland. This is beyond a horror movie.”

Fedoseeva, who is still hiding out in Moscow, hasn’t gotten a text from Grishin in years, but she remains terrified of what else he might do. In 2019, a Russian court sided with her and dismissed one of Grishin’s lawsuits, which claimed that she entered into their marriage with dishonest intentions to take his money. He is still suing her and Sulkess in the United States, where their allegations of harassment are pending as well.

Fedoseeva installed security cameras at her home and thinks about hiring a security guard, though she dwells on the risk: “There is always concern that he hires someone to get close to me to hurt me.” Sulkess worries about her friend: “She said to me the other day, ‘I feel like the light inside of me is just dying.’ She’s really strong in this, but she’s so tired.”

At the conference table in San Francisco, Sulkess and Kevorkian sit with their documents organized in front of them, discussing whether to go back to law enforcement. “I have lost confidence in [them] at this point,” Sulkess says of the police. And all the meticulous documentation, the years of her life wading through 421 Media’s memes and Grishin’s social media, has taken a toll. “The last thing I want to have happen is for this situation, because I go so deep into it, to take every part of me with it,” she says, looking up. “I wake up thinking about it. I go to sleep thinking about it. It doesn’t end.”

“I can relate,” Kevorkian adds with a sigh. “I could be sitting watching Russian cartoons, completely like a comedy, no drama, nothing suspenseful, and boom, I’m flashing back to Jamaica.”

“It’s so dark,” Sulkess agrees. “You’re constantly sitting in Sergey Grishin’s head.”

Sulkess, now living in California, daydreams sometimes about what it might be like to have her old life back, to have the time and energy to pursue her passions, to make another movie, instead of spending all her time on lawsuits. “But I also know I have to finish this,” she says. “I don’t need fucking Grishin’s dirty money. I don’t care about any of it. But I want this over.” She pauses, her eyes serious. “But like, how does it end? I don’t know.”