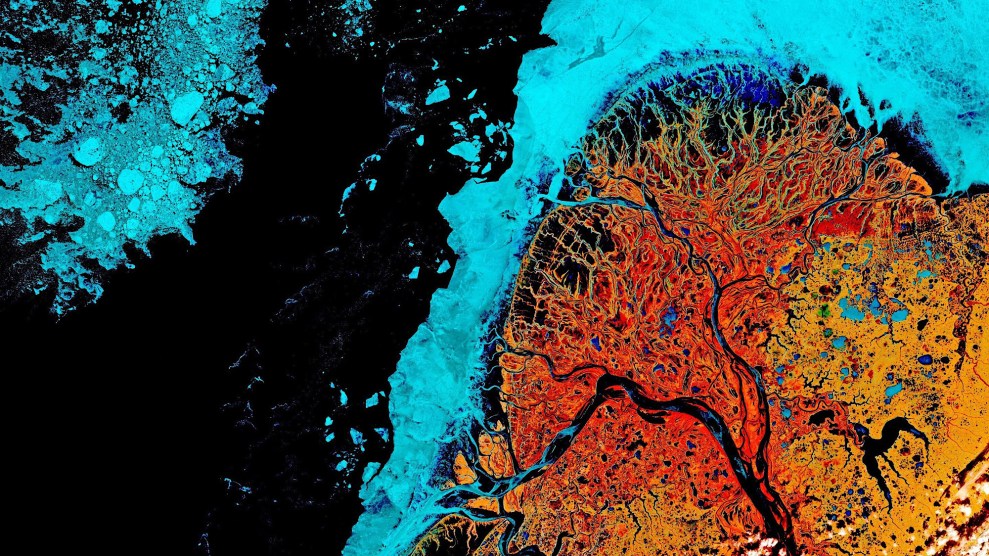

Based on data acquired by one of the European Union's Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites on May 15, 2021, this false-color image shows Alaska's Yukon River Delta during early spring thaw, including a blue halo of lingering sea ice. EUROPEAN UNION, COPERNICUS SENTINEL-2 IMAGERY

This story was originally published by Atlas Obscura and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A slice of brain, stained for scrutiny under the microscope. The cross-section of a head of broccoli, run through a funky filter. Or is what you see a dynamic, subarctic environment that researchers love to study, especially when it is rendered in a carnival of unnatural colors?

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, in southwestern Alaska, is one of the world’s largest deltas. The state’s two biggest rivers empty separately into the Bering Sea here, and the landscape between them is pocked with thermokarst lakes, shallow depressions created as permafrost melts and sags.

The northern section of the delta, where the Yukon River meets the sea, fans out in a dizzying network of waterways, and tundra gives way to marsh, meadow, and shrubland dominated by willow. While all of the massive delta is of interest to science, it’s this fan-shaped grand finale of the Yukon that’s been showcased in numerous, eye-catching false-color images over the past two decades (you can even buy prints of them on Etsy).

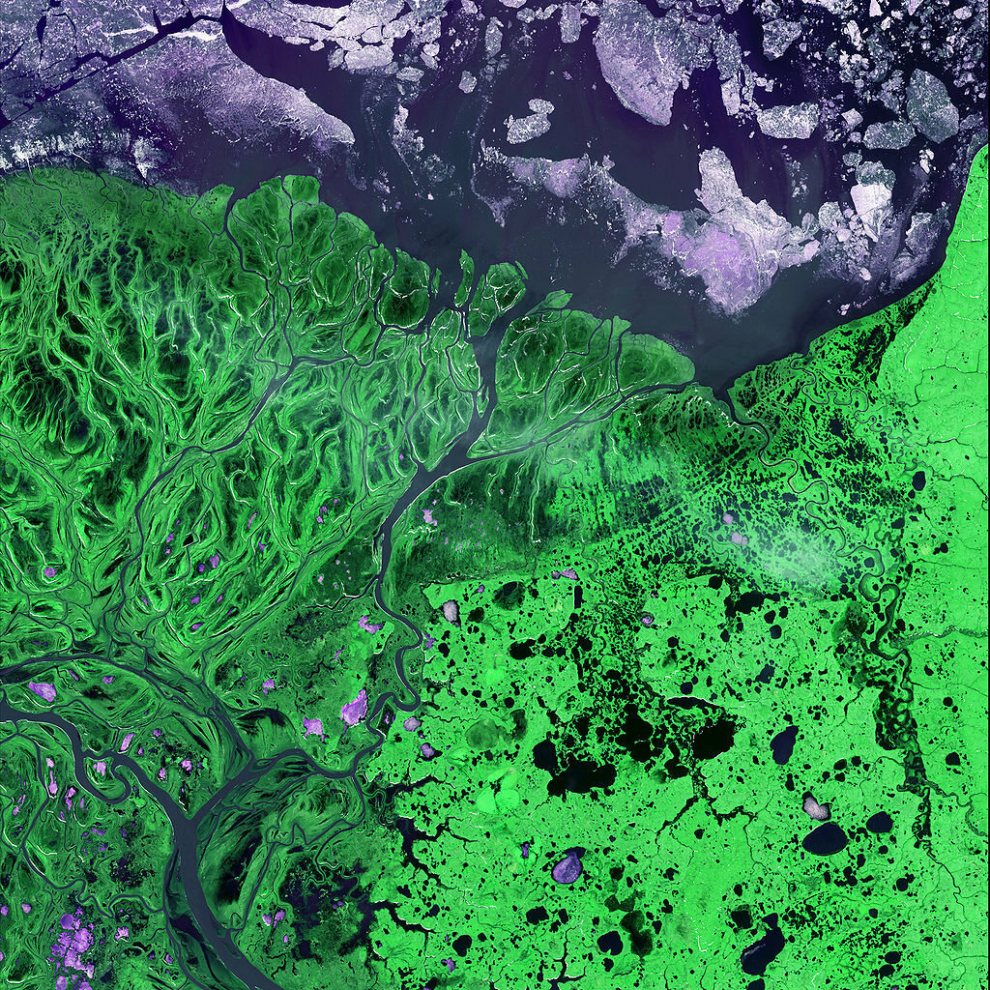

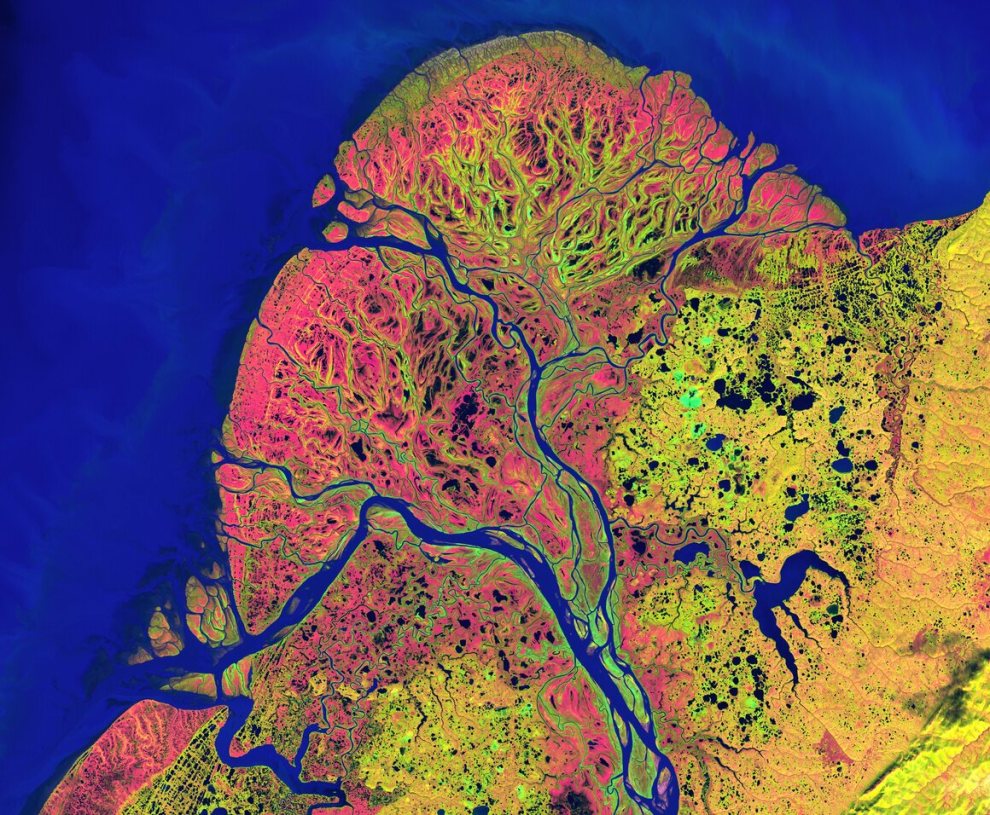

Unlike photographs, false color satellite images are data-crunched representations of different wavelengths of light that include those not visible to the naked eye. For landscape images such as those of the Yukon Delta, instruments on satellites passing overhead collect measurements of different bands on the electromagnetic spectrum. Data from these bands, when combined, can reveal the landscape in a new way. For example, combining the measurements of near infrared, and visible red and green, light can map the distribution and health of vegetation. That’s because stressed plants absorb or reflect various wavelengths of light—visible and non-visible—differently than healthy plants do.

A composite image of natural-color water and false-color land, acquired by NASA on May 29, 2021, highlights healthy, growing vegetation in bright green.

Joshua Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory

An enormous range of information, from the depth of a body of water to hotspots lingering after a fire, can be gleaned from combining these measurements, and then visualizing them within the visible spectrum with these false-color images.

“False-color infrared imagery like these examples normally include two infrared bands and one visible band,” says Matt Macander, senior scientist at Alaska-based scientific research and support firm ABR. Macander and his colleagues have done extensive mapping, modeling, and imaging work, including of the Yukon Delta. He says false-color imagery is especially good at highlighting specific features, such as open water, ice, shrubs, and bare ground, in complex environments. “The Yukon Delta is a wild patterned mosaic,” he adds. “There is a ton of information in infrared bands that is not present in the visible.”

From a vantage point much closer to the ground, in natural color, the Yukon Delta is still a spectacular sight.

Andrea Pokrzywinski, CC By 2.0/Flickr

The delta attracts such scientific interest because it’s a large transitional area between land and water, freshwater rivers and salty sea, tundra, forest, and wetland. It’s also prone to dramatic seasonal shifts, from winter snow and ice to spring flooding—and an impressive load of sediment carried into the Bering Sea—followed by rapid plant growth in summer. False-color images show all these varied, dynamic elements with far greater detail than a natural-color image ever could, making it valuable proving grounds for testing large-scale hypotheses, including modeling permafrost melt and climate change-related flooding patterns.

Macander says false-color images can have value beyond research for the government agencies and other entities that produce them, including getting the public excited about science. “For these outreach applications, someone probably tweaked the image color balancing knobs,” he says. “For scientific purposes the values in the imagery are meaningful but you can make pretty pictures without worrying about that.” We agree, and here are some of our favorite, frame-worthy views of the delta.

The branching patterns of waterways, technically distributaries of the Yukon, are highlighted in this 2002 USGS image.

USGS EROS Data Center Satellite Systems Branch/Wikimedia Commons

A natural color image of the delta from September 2002 shows massive amounts of sedimentation in the Yukon River and Bering Sea.

Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon/NASA Earth Observatory

Produced from data collected by the USGS in September 2002, this false-color image of the delta highlights autumnal vegetation.

U.S. Geological Survey/Public Domain

This 2011 image combines data from the European Space Agency’s Earth observatory satellite Envisat taken on three occasions over a six-month period, from November 2009 to May 2010. The complex color scheme shows changes over time in temperature, surface water, and other aspects of the landscape.

European Space Agency, CC By SA 3.0 IGO