Original image: <a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ursus_maritimus_Steve_Amstrup.jpg">Fish and Wildlife Service</a>

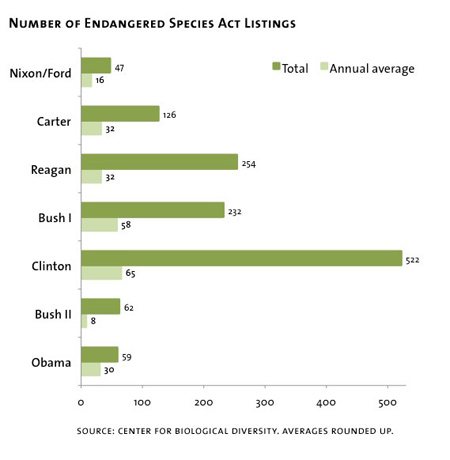

By the time he left office, President George W. Bush wasn’t exactly known as a friend of endangered wildlife. Over eight years, his administration protected 62 species of domestic animals and plants under the Endangered Species Act. By contrast, Bill Clinton had declared 522 species endangered during his two terms. (See chart below.) On average, Bush added eight new species to the list annually, the slowest pace of any president since Richard Nixon signed the ESA into law in 1973.

When Barack Obama took office in 2009, conservationists expected him to pick up the slack as well as end the outgoing administration’s policy of blocking, delaying, and politicizing endangered-species listings. In April 2009, the president took a swipe at his predecessor, declaring that the ESA had been “undermined by past administrations,” and all but promising to apply the law more aggressively: “We should be looking for ways to improve it—not weaken it.”

Yet two years later, little has changed, to the frustration of some wildlife advocates. Late last month, for example, the Interior Department upheld the Bush administration’s decision not to list the polar bear as endangered despite the rapid loss of its arctic habitat. If the bear were designated as endangered, it could legally obligate the government to adopt a more aggressive climate policy. “The Obama administration delivered a lump of coal to the polar bear for Christmas,” said the Center for Biological Diversity’s Kassie Siegel, the lead author of a 2005 petition to protect the bear. “Once again President Obama’s interior department has sacrificed sound science for political expediency, and the polar bear will suffer as a result.”

Obama is barely beating Bush at protecting new endangered species—and he’s far behind his Democratic predecessors. So far, his administration has added 59 species to the endangered list. However, that includes 48 species from the Hawaiian island of Kauai that were originally cleared for approval by the Bush administration.

“They have protected new species at a very slow rate,” says Andrew Wetzler, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s land and wildlife program, “and they have really not demonstrated that wildlife conservation is a priority.” Obama and Interior Secretary Ken Salazar “don’t have the ideological opposition to endangered species protection of the past administration,” says Noah Greenwald, the endangered species director at the Center for Biological Diversity, but “they haven’t really aggressively turned the program around or been effective at getting it started. They are sort of in this Neverland.”

The Fish and Wildlife Service, which oversees ESA designations for most species, blames the slow pace on a lack of resources and a barrage of lawsuits from environmental groups suing to get species off the waitlist for protection. “It has nothing to do with the administration,” says Lora Zimmerman, a biologist with the FWS’s endangered species listing branch.

The Fish and Wildlife Service, which oversees ESA designations for most species, blames the slow pace on a lack of resources and a barrage of lawsuits from environmental groups suing to get species off the waitlist for protection. “It has nothing to do with the administration,” says Lora Zimmerman, a biologist with the FWS’s endangered species listing branch.

Currently, 251 species are waiting for a final decision on whether they will join the endangered list; some, such as the Montana Arctic grayling and Oregon spotted frog, have been in limbo for more than two decades. Environmental groups estimate that it would cost $200 million to eliminate the backlog. However, the Obama administration proposes cutting the FWS’s 2011 listing budget by nearly 5 percent, to $20.9 million.

Since it went into effect nearly 40 years ago, the Endangered Species Act has safeguarded nearly 600 species of animals and 800 species of plants. Although only 13 species have bounced back enough to be removed from the list, studies show that the longer a species is protected under the ESA, the less likely it is to go extinct. While some of these species may sound ridiculously inconsequential or obscure—like Brown’s pigweed or the ponderous siltsnail—giving them endangered status has the added benefit of preventing the bulldozing of the wild places they inhabit.

Not surprisingly, that’s made the ESA a perennial target of developers and their allies in Washington, DC. At no point was the anti-ESA backlash stronger than during George W. Bush’s two terms. In 2007, the Interior Department inspector general found that a political appointee in the department had repeatedly and improperly overruled FWS scientists who wanted to add species to the endangered list. The administration also jeopardized endangered species, such as when it allowed up to 70,000 protected adult salmon in the Klamath River to die off in 2002. Late in his final term, Bush undercut the ESA by exempting thousands of federal activities, including the approval of coal mines and offshore oil rigs, from review by wildlife agencies.

Obama’s stance on the ESA has broken with his predecessor’s in notable ways. Interior Secretary Salazar quickly undid many of Bush’s eleventh-hour exemptions. In late 2009, the administration proposed a 128-million-acre tract for polar bears in Alaska, which would be the nation’s largest refuge for a threatened species. Environmental groups have hailed a federal decision to protect threatened salmon by curtailing water projects on California’s Sacramento River. “The people running the show now have a long history of concern for conservation,” says John Kostyack, who oversees conservation efforts for National Wildlife Federation. “It’s just a different crowd and a different sentiment.”

But some environmentalists see the current administration continuing the political meddling in scientific decision-making that became common during the Bush administration. Several environmental groups such as Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility and WildEarth Guardians strongly opposed Sam Hamilton, Obama’s pick to head the FWS. As the head of the agency’s southeastern division under Bush, Hamilton rubber-stamped suburban sprawl that has decimated the population of the endangered Florida panther. (Hamilton died in February 2010; Obama’s new nominee, Dan Ashe, is less controversial.) Under Bush, Interior officials concluded that the worst-case scenario of a deepwater-drilling spill in the Gulf of Mexico would not harm endangered species such as sperm whales and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles, allowing new drilling operations without detailed environmental reviews. This past August, in the wake of the BP disaster, the Obama administration ended the practice, but only for new deepwater-drilling permits. Wells in shallow water still do not have to comply with the ESA, nor do nearly 30 deepwater projects that were underway before the spill. And Salazar has also upheld a Bush-era policy that prevents the government from using environmental threats to ESA-protected species to justify taking action to reduce carbon emissions.

Critics say much of the problem originates with Salazar, a former rancher who came to Washington with a reputation as a less-than-wholehearted supporter of the ESA. In 1999, shortly after taking over as Colorado attorney general from Gale Norton (who had become Bush’s interior secretary), Salazar threatened to sue the FWS if it listed the black-tailed prairie dog as a threatened species. (Prairie dogs are reviled by ranchers because they eat grass and dig holes that can injure cattle.) In late 2009, the Interior Department rejected a petition to give the rodent endangered status.

Salazar has also joined an ongoing scuffle over the endangered Northern Rockies gray wolf, which was nearly wiped out by ranchers. He signed off on a plan, enacted shortly before Bush left office, in which the wolf would be removed from the endangered list in Montana and Idaho. Last August, a federal judge overruled Salazar, concluding that the wolf population throughout the northern Rockies, which includes parts of Wyoming, must be protected as a whole. In December, the Interior Department signaled that it could back a bill delisting the wolf and the grizzly bear in all three states, which would effectively prevent lawsuits from environmental groups. “Had Bush even tried something like this, there would have been people screaming bloody murder,” says Jeff Ruch, the president of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility.

Rick Sayers, who oversees most endangered species issues for the FWS, says that despite the interior secretary’s involvement in the gray wolf case, Salazar has not put any undue pressure on agency staff. The administration puts “a very strong emphasis on making our decisions based on whatever the best scientific data directs us to do,” he says.

Yet Ruch says that in 2010 alone, 25 federal wildlife scientists complained to him about political interference from the current administration. They say that their supervisors at the FWS and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration have watered down their reports, barred them from issuing findings that might be used to protect species, and limited the collection of scientific data to mask bad news about struggling species. Several FWS and National Park Service scientists told Ruch that they were steamrolled in a recent decision to allow off-road “swamp buggies” in 40,000 acres of protected panther habitat in South Florida.

Ruch believes that these kinds of decisions are being made by holdovers from the Bush administration whom Interior officials are reluctant to challenge. The Obama administration is “sort of on par with the Bush administration,” Ruch concludes. “There hasn’t been much change in policy or personnel. I think that they consider wildlife protection a distraction.”