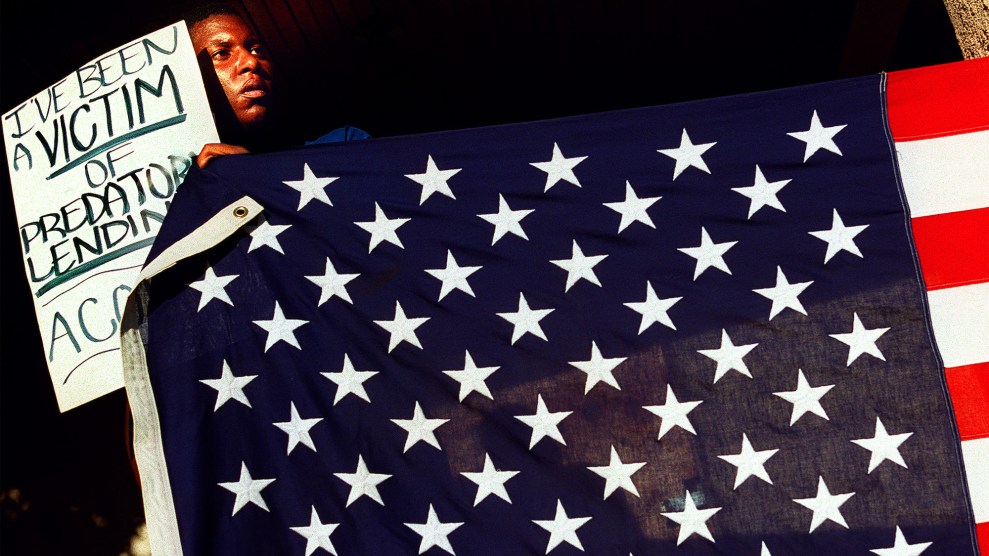

For many, America is unlivable. Across the country, homeownership seems like a mirage from another era. In many blue cities and states, even renting is tough. In California, the median price for a home has broken past $800,000. The rate of homelessness nationwide has risen four years in a row. A quarter of 2020’s unhoused individuals lived in either New York City or Los Angeles. All of this clearly—as we are told time and time again—constitutes a “housing crisis.”

But what exactly does the phrase mean? There’s a you-know-it-when-you-see-it quality to the term that makes its vagueness easy to ignore. Someone reading Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper, Evening World, in the 1920s would have associated “housing crisis” with overcrowding and sordid living conditions in Brooklyn’s tenements. A subscriber to the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle in the late ’40s would have understood it to mean a shortage stemming from low rates of housing production during the war effort and the return of veterans from Europe. And, after 2008, the prevailing catastrophe was the collapse of the housing bubble and the resulting subprime mortgage crisis that set off the Great Recession.

“Housing crisis” has been used as a metonym on so many occasions over its near-constant circulation since the early 20th century that it can be hard to locate a defining characteristic. As Gertrude Stein might have said, a housing crisis is a housing crisis is a housing crisis.

Jacob Anbinder, a historian of housing and infrastructure at Harvard, points out that even the current use of the term tends to conflate two related but distinct problems. The first is the insane cost to buy and rent in wealthy coastal cities; the second is the affordable housing crisis, a persistent lack of access to permanent shelter among low-income Americans everywhere. One could argue, Anbinder says, that the second is more a “crisis of impoverishment” than an acute crisis of housing.

This conflation of the affordable housing crisis with the other housing problems has led Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, an activist and scholar, to argue that we should move away from using the term altogether. By deeming something a “crisis,” Taylor argues, we imply that it’s an extraordinary occurrence that can be alleviated through private-sector reforms, like the ramping up of housing production, without wrestling with the fact that, “as long as there is a price on shelter,” as she told the Nation, housing will be unstable for many.

On closer inspection, few seem completely happy with the term (except headline writers). To some socialists, “housing crisis” can imply that a series of modest policy adjustments can do the trick, rather than a major rethink in the way society is structured. To technocrats, the term is too malleable to capture the nuance of a hyper-particularized issue, from a local zoning law to the power of a NIMBY-ish neighborhood association. Indeed, in just the last two years, the Atlantic has applied the term both to the housing shortage and to the potential rise in evictions caused by Covid. These issues are intertwined but unique. A temporary eviction moratorium won’t help alleviate the general affordability problem in San Francisco. And a statute reforming minimum lot sizes would be small comfort to a family about to be kicked out of their apartment during a pandemic.

The political will to fix housing at times seems stalled in the same place as the term “housing crisis” itself: either mired in heady debates that avoid the specifics of how to fix a concrete, conditional issue (what to do with a surfeit of empty lots) or so specific as to miss the comprehensive social problem behind it all (poverty). The term can obscure both the problems we can wonk our way out of and broader critiques of the way our society is structured.

The word “crisis” was originally used to refer to a “decisive turning point” in a disease—the stage that determined whether a patient lived or died. But with housing, there’s never been any such turning point. Indeed, one striking feature of the housing debate is just how often the same arguments recur. And while we repeat ourselves, the unlivable prices, the casual dismissal of the poor as undeserving of shelter, and the infuriating lack of political will continue.