Before Patty Griffin became one of folk’s most critically acclaimed singer-songwriters, she sometimes had difficulty finding an audience for her wistful voice. When she tried to make ends meet a by auditioning to sing for a Downy fabric softener commercial a decade ago, she was rejected because of her distinctive melancholy sound. “They said, ‘It’s just too sad! Downy should not be sad,'” she says laughing today.

Music critics and audiences, though, loved the sad stuff—as well as the gospel, rock, alt-country, and other styles she’s dabbled in since her 1996 debut album. The Dixie Chicks, Bette Midler, and even American Idol winner Kelly Clarkson have recorded her songs. And on November 1, she took home the Americana Music Association’s artist of the year and album of the year awards for her CD Children Running Through.

Mother Jones spoke with her earlier this year while she was on tour in California.

Mother Jones: I hear you wrote the song “Burgundy Shoes” after someone challenged you to do a “happy song.” Do people often say your songs are too sad?

Patty Griffin: You know what? Most people like the sad songs. [Laughs]. Some of the oldest songs known to man are sad. Listening to a voice singing something sad is a really great way to help you to feel sad when you need to. [The person who challenged me] was my friend Craig Ross who writes songs, too. We both accused ourselves of really dwelling on the sad. We dug into our own cynicism and tried to find other stories to tell. I’m not sad every minute, so it’s weird to go and do a show and feel all happy to see the audience and you have nothing but sad songs to sing.

MJ: On the new album, you’re joined by Emmylou Harris for the song “Trapeze.” She’s singing a harmony line, but she has such a distinctive voice that it turns into a duet….

PG: I’ve been lucky enough to entice Emmy to sing on every record that I’ve made since 1997, so I earmarked that one for her to sing on. We went into the studio with her, and we were having such a good time hearing her do it, it really turned into a duet. I think that the soul she brings to that adds a lot to the feeling. She brought something to it with her singing that I couldn’t. You don’t hear women in their sixties, late fifties singing that much anymore. There’s something in that voice that you can’t get from a 30-year-old.

MJ: Speaking of that, I’ve noticed that you bring up the topic of age a lot in interviews—

PG: [Laughs.] I think the shelf life is much shorter for women in what I do. My business is pretty youth-oriented, and there are things that I have butted up against that have little to do with music and more to do with how I look and how old I am. I think getting dropped from my major [label] when I was 37 years old was the first sign of that. At 37, I was washed up! [Laughs.] And I thought, “I know I’m writing and singing better than a lot of these kids they’re bringing into this major label deal.” I mean, you get less attention, and you have to kind of remind people that you’re still here, and that you still could make money for them, even! [Laughs.] If they’d only let you.

MJ: You have a close relationship with the Dixie Chicks, who have recorded three of your songs. What do you make of the situation they’ve been through the last few years?

PG: It’s really horrible that a big corporation and a government would try to bring down these three women, you know? It’s horrifying. I never thought I would see anything like that in the United States—the book-burning, record-burning kind of thing. But I also think that they’ve grown out of it so much. They’re artists, and that’s what you get when you’re true to yourself sometimes. You’ve got to deal with that. And I don’t think it’s hurt them at all, really. I think it’s a lot more power they really didn’t know they could have.

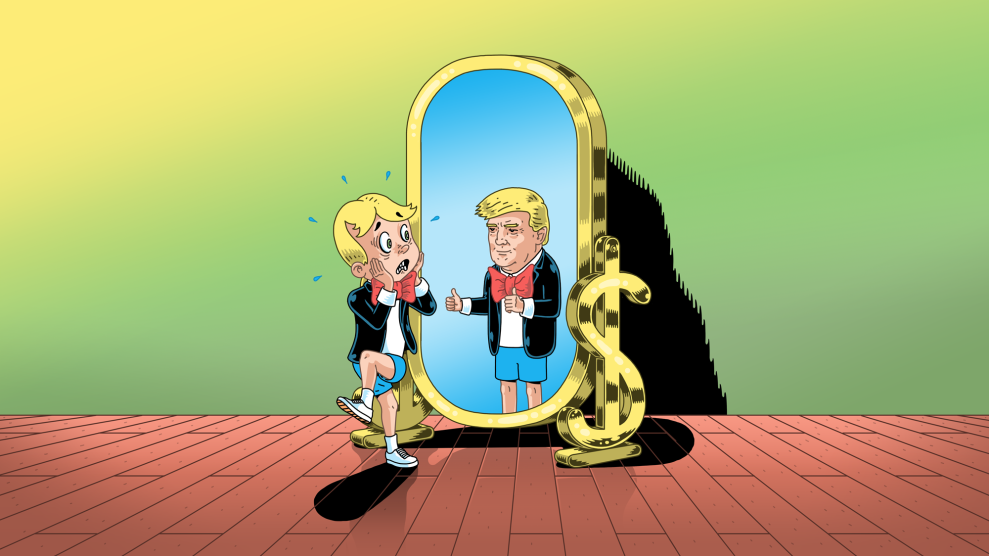

MJ: Like the Dixie Chicks, some of your songs are obliquely political, like “No Bad News” on your newest album. It can be interpreted either as a song to a former lover or to President Bush. The “sad little boy” in the song is…

PG: Bush. Oh yeah. [Laughs]. When I wrote that, it was still a little scary to go out and say you were against the war, and people come to my shows and they’ve got brothers and sisters in Iraq. I feel an obligation to express myself, to be true to myself, but I also feel like I’ve got to be responsible about the way that I do that. If I’ve got somebody out there who’s really sensitive and not ready to hear that the war is incredibly, incredibly horrible for everybody involved and there was no real reason to go in…if somebody comes to my show and their brother’s in Iraq, you know, they’re not ready to hear that yet. It’s not something I’m going to push on anyone. I don’t think that’s my job. But I have to get that off my chest at the same time. Some people get that right away—the political side. To other people it’s just a song about being mad at a boyfriend, and that’s the beauty of it.

MJ: If your boyfriend were George W. Bush.

PG: [Laughs.] Yes.

MJ: So you’re saying the way you get a wide audience to listen your message is by making your songwriting a little less explicit—

PG: I’m driven to write about what is going on in my life, and what is stoking my fires. But how do you go near that subject without excluding people who don’t necessarily see it that way? I don’t want to alienate anybody. I think that’s the root of the damn problem we have going on in this country. I really want to include everybody and I still want express myself. If that makes me a horrible, moderate, terrible person, then I guess that’s what I am.

MJ: A lot of your songs deal with guilt—

PG: Really? [Laughs.]

MJ:—and a lot of them look at it from a male point of view. I’m wondering what that’s about.

PG: Man, no one’s ever called me out on that! I’m not kidding. I was wondering when that was going to happen. Over the years, there has been a lot of poverty in my background, and frustrated men walking away from the families, and guilt about that. So I think it would make sense that some of these stories—which are not autobiographical, by the way—would just show up in the way they show up.

MJ: So the guilt is something that you’re observing in others?

PG: Oh my God! Are we in therapy? [Laughs.] You know, I grew up Catholic. I think you’re never going to lose that. I think it gives you this extra edge of responsibility for maybe things you aren’t necessarily responsible for.

MJ: Pop star Jessica Simpson, of all people, recorded your song “Let Him Fly.” I was wondering if you heard it, and what your reaction was?

PG: I’ve seen a version of it on YouTube. You know, you write your songs…it’s kind of like when you put songs on your record, you’re sending your kids off to school. They’re somebody else’s kids most of the time. They belong to the world. Because I only sing them on stage now and then. They’re not mine anymore.

MJ: Do you ever get tempted to join that world—to pull a Liz Phair and release a hyper-produced pop album?

PG: Oh, no. You know what would be fun to do is to do a Milli Vanilli kind of thing. [Laughs.] Write the songs, [but] get somebody else to go out and wear the flesh-colored body suit and the feathers and do the dance.

MJ: Are there any styles you sing along to in the car but you’d never try to record?

PG: For a while, I was the person with Public Enemy booming in my car at the stoplight. [Laughs]. I would never, ever attempt to do anything like that. It’s way out of my league, but I sure have a great love for it. Also, I don’t think I could be the singer for this, but I wish there’d be another group as great as En Vogue was. They were just out of this world, and they came along as this time where the music was all hair bands. I remember, [singing] “free your mind, and the rest will follow.” And I was like “thank God.”

MJ: There’s a musical that’s being developed based on your song that is premiering in May. When I think musicals, I think “Mary Poppins” and “Oklahoma,”—

PG: [Laughing.] Me too!

MJ: —and with those as the model I’d think you’d be the least likely singer in the world to write songs for a musical. Can you tell me more about it?

PG: Keith Bunin is a great writer, and he approached me five years ago about…he didn’t want to call it a musical at first, because I think he’s afraid of that, too! He said, “every time I listen to your music, I see scenes that I want to write, and maybe we could figure something out where I’m doing a play and let your music is involved.” And I said, “OK, so it’s a musical, but he doesn’t really want to call it that.” I have a lot of admiration for his writing. And I [was] not a big fan of that genre, but I thought, “why not try this? The only reason to not try this is because I’m a snob.” [Laughs.] And that’s not a very good reason to stop yourself from doing anything. I was really scared to see it, and actually it turned my mind around about that whole genre, seeing those singers perform [my] songs and making them their own. There’s a real talent to that. I have listened to some Broadway music since then, and have a lot more respect for that world than I used to.

MJ: When I saw perform a couple years ago, you sang “Kite Song,” which is a pretty deeply personal and emotional song with political undertones. And you introduced it by saying simply “this is a song about kites”—and nothing else.

PG: Yeah. [Laughs.]

MJ: Do you have an aversion to over-analyzing your songs?

PG: Yeah. I am not in favor of over-analyzing my music, because I’ve been around my own songs long enough to know how what they mean to me performing them can shift year after year. There are a billion ways to perceive them, and I want people to kind of have their own version of that.

MJ: Alright. Thanks so much for your time.

PG: No, no. I feel like I should pay you a hundred bucks for the therapy, man!