Tufts University medical students in anatomy lab.Jessica Rinaldi/Getty

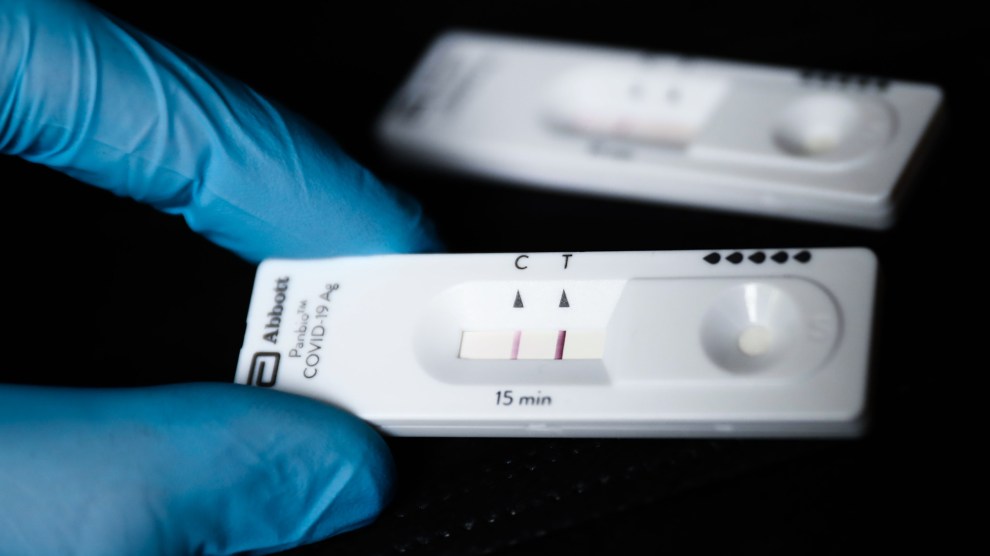

One day in June, medical student Jasmina Ehab carefully examined a child’s rash. For Ehab, who is in her fourth year at the University of Southern Florida’s Morsani College of Medicine, this was an easy one. “A rash is a rash, and we know what it is once we see it,” Ehab told me. And this rash was no different. It had honey-crusted lesions, indicative of impetigo—a skin infection easily treatable with a topical antibiotic. The kid would be fine.

The interaction was typical, but the circumstances surrounding it were not. Ehab examined the rash from a clinic, but she was the only one in the room. The patient’s mother hovered her smart phone over her child’s skin—neither of them had left their house.

Ehab learned to do virtual appointments like this on the fly last spring: Before the pandemic hit, telemedicine was largely absent from her classes. This year, things will be different: Remote visits are now covered in each section of clinical education at the medical school—from pediatrics to internal medicine to psychiatry.

Across the country, medical schools have pivoted to meet the demands of a society under quarantine: virtual classes, reformatted clinical rotations, remote residency interviews. But for aspiring physicians, hands-on experience is also essential: Surgery and bedside manner can’t be perfectly simulated in a web module. “At the end of the day,” says Dr. Kevin Krane, vice dean for academic affairs at Tulane University School of Medicine, “the MD is not an online degree.”

So how can medical schools maintain student safety while offering essential in-person training? The answer, according to some experts in the field, is to embrace long-proposed changes to the way medicine is taught. For years now, the American Medical Association—which co-sponsors the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the accrediting body for medical schools in the US—has been contemplating a shift from rigid conventional instruction to more fluid, individualized lesson plans, says Dr. Susan Skochelak, vice president for medical education at the AMA. With traditional instruction impossible in the pandemic, some schools have begun to try those approaches. “This is an area that the pandemic has accelerated and these changes will be with us into the future,” she said.

Under normal circumstances, curriculum change moves slowly: year of planning, a year of implementation, a year to see if it worked, and three or four years to see the effect on test scores, says Dr. Deborah DeWaay, associate dean for Undergraduate Medical Education at University of South Florida. But COVID-19 threw that out the window. As this academic year was swiftly planned over the summer, the “worst fear” for Dr. DeWaay is a new crop of graduating doctors in 2021 who are missing the essential time in clinical settings that they’d have had under normal circumstances.

Which is why just about every medical school in the country has spent the last several months deciding which academic experiences can be replicated online—and which ones still must happen in person. When the pandemic first arrived in March, the Association of American Medical Colleges quickly announced recommendations that ended normal course instruction. Students were to be pulled from clinical settings, like hospitals and primary care facilities, prompting a mad dash by medical schools to find them alternative work. At USF, for example, third year students shifted to independent study, focusing on classroom theory they’d be learning in their fourth year to make effective use of time.

Administrators have used the summer to prepare courses for the fall. The digital transition for first and second years, before students typically interact with patients in clinical settings, was relatively painless. Most often, those years are quintessentially academic: big lecture halls, presentations, exams, studying galore. Moving those elements online was straightforward. In fact, it’d been gradually happening in the years leading up to the pandemic. In recent years, more and more instructors have recorded and uploaded their lectures for absent students. Medical students found that format more convenient, Dr. Krane says. “They will learn the content whether they sit in the classroom or not, as long as they’re given good objectives and good resources.”

Still, “you can’t teach someone to listen to a heart on a real patient virtually,” Dr. DeWaay says. And even if you could, “You go from being completely online to now you’re a third year and you have to put twelve hour days in at the hospital—that’s gonna be really challenging if you’ve been in pajamas for two years.” The University of California-San Francisco is planning a hybrid curriculum for its first and second years, to ensure essential experiences, like cadaver lab—dissection and surgical training with a frozen corpse—may still take place in person. The tentative plan is for campus to be open three days a week, with one third of a class, about 50 students, having access to campus on each day. If a lesson necessitates an in person lab—a guest lecturer, anatomy lab, physical exams, dissections—students will come in that week, and split into groups no larger than 10.

Restrictions on how to bring in students from outside the classroom is also changing what’s happening inside. Take anatomy, for example. Historically, anatomy lab has been a three-pronged affair: cadavers lab, ultrasound, and cross-sectional—which is a two-dimensional perspective viewed through CT or MRI scans. When Dr. DeWaay was a student, those labs were spread out across four years of medical school, which made tying them together conceptually difficult. “When I did anatomy, I walked in and spent four hours dissecting and hoping I was understanding what I was supposed to be,” she said. Later, in the third year, students would revisit anatomy to learn from the cross-sectional perspective. “Some people can do it intuitively—for rest of us it’s a very challenging jump,” she said. A few years ago, USF altered its curriculum to combine the three components into one lab space to tie the three perspectives on the human body together. The pandemic has brought about the next step in evolution. Students now complete the ultrasound and cross-sectional on their computers. There’s no need to stick around in the lab space to view them—so they’ve gone remote.

Other schools are considering ditching cadaver lab entirely. Citing the high cost of working with cadavers and the risks of exposure to formaldehyde, the newly-accredited Kaiser Permenante Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine has embraced virtual alternatives, which also allow instructors to easily simulate various medical conditions. At Tulane, Dr. Krane says some of the lab is now done digitally, but that it’s still essential that students come in and see the real thing. “Interaction with a cadaver is important for the development of professional identity,” he says. The opportunity to see and relate to a body—in all of its humanity—is visceral. “Really, there’s a sense that the cadaver is your first patient.”

While schools are considering cutting some parts of the curriculum, they’re also adding new material: USF has tried to convert conversations on lingering racial disparities into its lesson plans. “If you look at the last several hundred years in the country, there’s a pandemic happening we don’t want acknowledge,” Dr. DeWaay says. The curriculum committee decided to address demographic disparities in access to healthcare “with same rigor that we’ve been treating this pandemic.” Thus, administrators are now drawing up plans for a course that confronts racism in medicine to add to an already-existing social determinant of healthcare disparities program. UCSF, meanwhile, has shifted the focus of its health and society course to analyze the disparities of COVID-19’s effect on different communities. And according to Dr. John Davis, associate dean for curriculum at UCSF, course directors are also adding seminars on how healthcare systems handle pandemics.

As students get deeper into their academic careers, curriculums offer less to compromise over. For most schools, year three marks a major pivot point from theory to practice. Students begin clinical rotations, where they shift between essential sectors of the field—OBGYN, pediatrics, internal medicine—getting a taste of each specialty for approximately ten weeks at a hospital.

At USF, the pandemic postponed rotations from June 1 to August 3. For third year students in some clinical rotations, that means cramming what would usually be 12 weeks into eight—and hopefully being back on a normal schedule in fall 2021. “Can I do more nights? Can I do more weekends?” She says those were the questions curriculum heads were asking themselves as this academic year drew closer. In San Francisco, Dr. Davis says in addition to a tight schedule, the rotations are also subject to rigorous safety standards: UCSF isn’t permitting students to directly engage with COVID-19 or COVID-suspected patients.

Under normal circumstances a clinical rotation lasts between two and three months. Instead of assessing students at the end of their rotation, “when they’ve met the objectives, they move along,” Dr. Davis said. Organizations like the AMA have long contemplated this, and UCSF is taking the opportunity to put it into practice. Other schools, like Duke University and USF, are making rotations pass-fail. Diana Dayal, a fourth-year medical student at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, says she welcomes the change. Rather than a highly charged environment where students are expected to answer esoteric questions with speed and accuracy, “you can get a question wrong, or ask a question that sounds stupid,” she says. “You can admit to not knowing how to do something without it being punitive.”

Dr. Skochelak at the AMA points out a common misconception surrounding medicine: Learning doesn’t end with medical school. Life as a resident or fellow is certainly higher stakes, but receiving institutions are well aware of the circumstances surrounding the class of 2021. That probably won’t change patient experiences too much: Even without a pandemic, the healthcare system is full of physicians who months before were still students. “I don’t think there’ll be people falling through cracks,” Dr. Skochelak says. “But will they be moving onto the next stage of training with some gaps? That’s certainly possible—and we need to be prepared for that.”