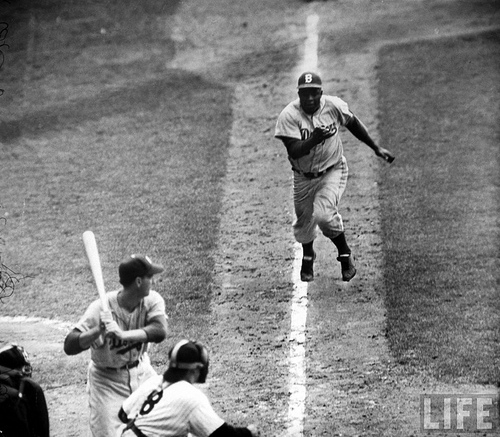

Jackie Robinson steals home. Flickr/stechico (Creative Commons)

Lester “Red” Rodney, arguably one of the most influential sportswriters in the profession’s history, who used his sports page in the communist Daily Worker newspaper to campaign against baseball’s color line, to cover Negro League stars like Jackie Robinson and Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, and to pioneer a brand of sports journalism with a conscience, passed away this week. He was 98.

Dave Zirin, who’s written extensively about Rodney in his must-read book What’s My Name, Fool? and elsewhere, remembers Rodney in a wonderful homage over at Huffington Post today, parts of which I’ve included here. As Zirin writes, one of the reasons Rodney was never included in the pantheon of sportswriters came down to the masthead on his paper:

If you have never heard of Lester Rodney, there is a very simple reason why: the newspaper he worked at from 1936-1958 was the Daily Worker, the party press of the U.S. Communist Party. Lester used his paper to launch the first campaign to end the color line in Major League Baseball. I spoke to Lester about this in 2004 and he said to me, “It’s amazing. You go back and you read the great newspapers in the thirties, you’ll find no editorials saying, ‘What’s going on here? This is America, land of the free and people with the wrong pigmentation of skin can’t play baseball?’ Nothing like that. No challenges to the league, to the commissioner, no talking about Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, who were obviously of superstar caliber. So it was this tremendous vacuum waiting.”

The man who stepped into that vacuum, Jackie Robinson, would go on to become a lightning rod for the intersection of race issues and sports. Robinson fascinated Rodney, and the writer always felt drawn toward the fiery, intelligent, sublimely talented first baseman:

As Lester fought to end the Color Ban, he also never stopped highlighting and covering the Negro League teams, giving them press at a time when they invisible men outside of the African American press. But it was Jackie Robinson who captured Lester’s imagination. Armed with a press pass to the Ebbets Field locker room, he saw up close the way Robinson was told to “just shut up and play” despite the constant harassment during his inaugural 1947 campaign. “Jackie was suppressing his very being, his personality,” said Lester. “He was a fiercely intelligent man. He knew his role and he accepted it. And the black players who followed him knew what he meant too.” …

Lester would still become emotional when he recalls Jackie Robinson and his impact. “There are very few people of whom you can say with certainty that they made this a somewhat better country. Without doubt you can say that about Jackie Robinson. His legacy was not, ‘Hooray, we did it,’ but ‘Buddy, there’s still unfinished work out there’ He was a continuing militant, and that’s why the Dodgers never considered this brilliant baseball man as a manager or coach. It’s because he was outspoken and unafraid. That’s the kind of person he was. In fact, the first time he was asked to play at an old-timers’ game at Yankee Stadium, he said “I must sorrowfully refuse until I see more progress being made off the playing field on the coaching lines and in the managerial departments.” He made people uncomfortable. In fact it was that very quality which made him something special. He always made you feel that ‘Buddy, there’s still unfinished work out there.'”

Sadly, there aren’t many sportswriters out there today—Zirin an obvious exception—who cover not just balls and strikes but the political and economic and social undercurrents of the sporting world. Nevertheless, Rodney showed how influential and powerful a sportswriter with a keen eye, a conscience, and a few column inches can be. For further reading on Rodney, I recommend Irwin Silber’s Press Box Red.